Silent Scars

Dating violence is a pervasive issue that inflicts profound wounds on victims, both visible and hidden. The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence reports that 1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men have experienced intimate partner physical violence such as slapping, injury and sexual abuse.[1] These issues can be difficult to notice from the outside of a relationship, allowing abuse to continue while mental scars shape victims' psychological and physical well-being. The connections between dating violence, abuse, and mental health shed light on the silent struggles endured by survivors.

The Spectrum of Abuse

Abuse in dating relationships takes on various forms - from physical violence to emotional manipulation, coercion, and even digital harassment. The dynamic that leads to violence in a relationship is a power imbalance when one person gains power and control over the other.[2] This may take the forms of threats, intimidation, financial abuse, stalking and isolation[3] and this multifaceted spectrum of dating violence can leave victims feeling trapped in a cycle of abuse. Dating violence shatters victims' sense of security, trust, and self-worth, planting the seeds for lasting mental health challenges.

Examples of the warning signs of abusive behaviors include:[4]

Using force or coercion to initiate sexual activity

Attempting to isolate one from their family or friends

Using threats

Breaking objects, creating noise or yelling to establish intimidation

Having a history of abuse in past relationships

Expressing control financially (refusing for a partner to work)

Expressing control over where a partner goes, what they wear, who they speak to...

Frequent mood swings and shifts when in public compared to in private

Constant jealousy

Erosion of Emotional Well-being

The emotional toll inflicted by dating violence relates to poor mental health outcomes. Adolescent dating violence is particularly prevalent (i.e., 1 in 3 adolescents have experienced an abusive or unhealthy relationship) and is a predictor of partner violence as an adult.[5,6] Pérez-Marco et al. (2020) note that adolescents characterized dating violence as psychological, sexist, and verbal types of violence.[7] For example, blackmailing or damaging a partner’s dignity are examples of psychological violence.[8] Further, Piolanti et al. (2023) note that adolescent dating violence contributes to increased risk-taking behaviors such as marijuana and alcohol use, and negative mental health such as victimization, a common result of physical or emotional abuse.[9] These poor outcomes were more common among females when compared to males. Additionally, among 116 married women experiencing domestic abuse, Malik et al. (2021) found that abuse was associated positively with depression, anxiety and stress.[10] Domestic abuse was also related to a decreased quality of life.[11] The constant undercurrent of fear, anxiety, and uncertainty from degradation and physical attacks can erode victims' emotional well-being and even skew the perception of their relationship as being “normal” amidst high psychological distress.

Emotional abuse is related to:[12]

Complex Trauma & Misconceptions of Dating Violence

Exposure to dating violence often inflicts complex trauma, or unique forms of psychological injury that can lead to enduring emotional and mental turmoil. The patterns of abuse – the relentless cycle of tension, explosion, and reconciliation – carve a pattern of fear in victims' minds. Complex trauma can manifest as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders and depression.[13] From an external perspective, relationship violence is commonly misunderstood as bystanders may question why a victim stays in their violent relationship if they are being abused. It is so easy to ask, “Why don’t they just leave?”[14] However, there is a deep manipulative aspect to dating violence that maintains a harmful cycle.

De Sousa et al. (2023) found that among participants ages 15-22 in relationships, control tactics were predominantly isolation, domination, and emotional manipulation.[15] These controlling dynamics establish heavy power imbalances that lead to both a bystander's and a victim's blindness to the harm of a relationship. For example, an abusive partner may conceal their violent tendencies when in public or around peers, but when in private with their partner, inflict abuse. The victim may even develop learned helplessness, in which they have repeatedly experienced violence and eventually stop resisting or trying to change the uncontrollable circumstance. Additionally, it is common for victims to find comfort in their abusive relationship, as they are manipulated to believe that they abuse because their partner “loves them,” as Shawn Guy writes for Genesis Women’s Shelter in an article about teen dating violence.[16] This occurrence is sometimes referred to as Stockholm syndrome, or the psychological response of a positive connection to an abuser.[17]

The Path to Recovery: Empowerment and Support

Victims of dating violence find it challenging to escape their abusers. Feelings of shame, guilt, and societal stigma can create barriers to seeking help. Additionally, financial dependence and isolation enforced by abusers can make it difficult for victims to end relationships.

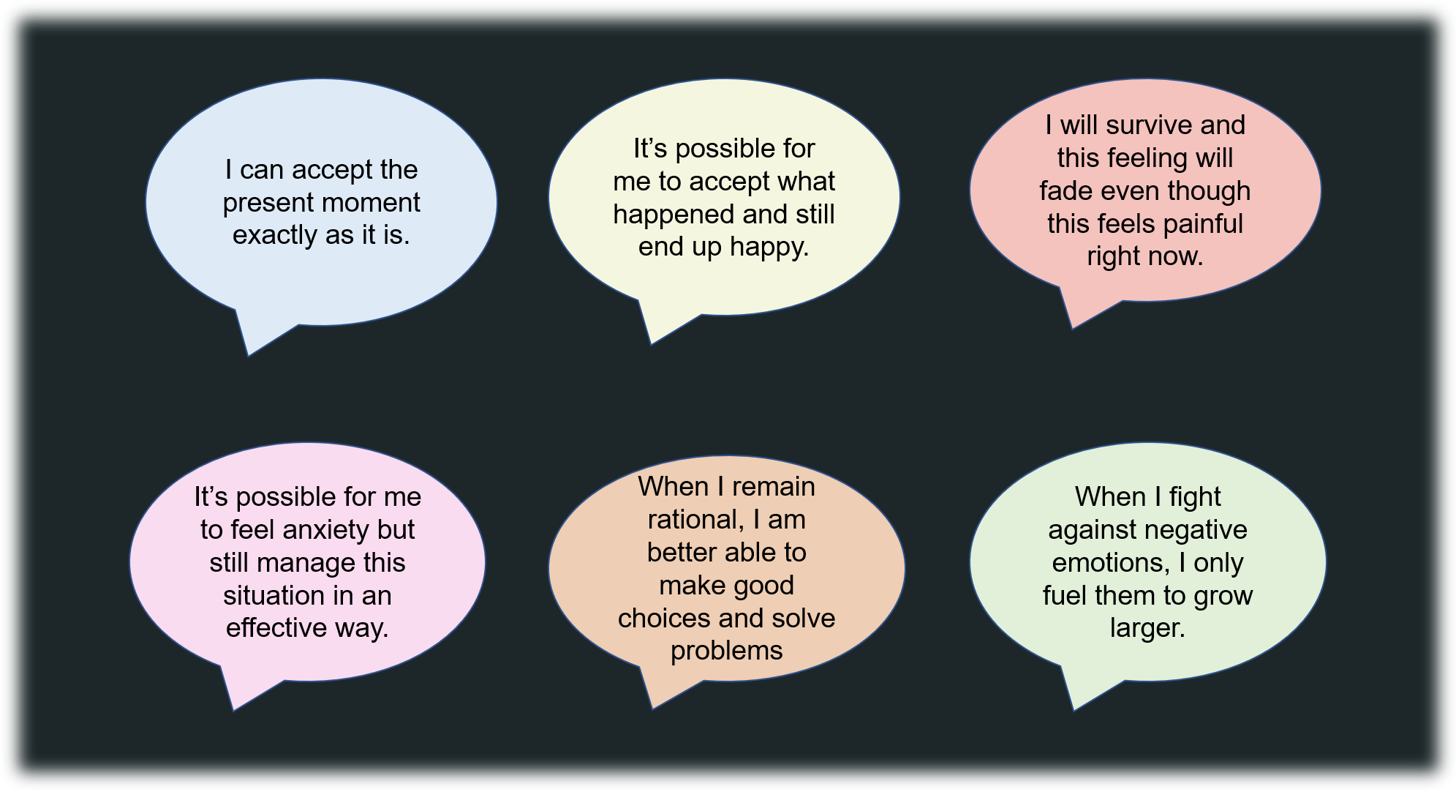

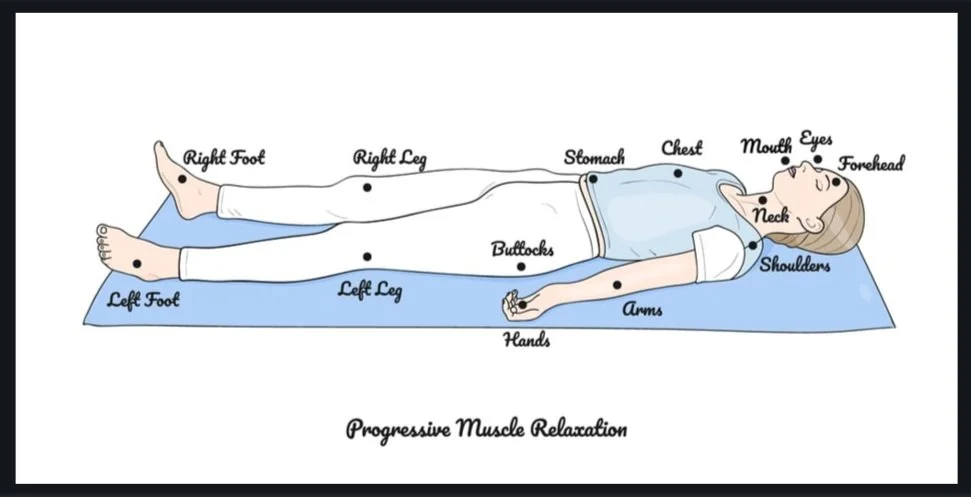

Professional help through therapy can help survivors regain a sense of agency and control over their lives to minimize the long-term effects of abuse and trauma. For example, Karakurt et al. (2022) found that cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness, motivational interviewing and expressive writing have led to successful results in increasing empowerment among women who had experienced intimate partner violence.[18] These modalities lowered stress and depressive symptoms, as well.[19]

Empowerment becomes a sign of hope as victims rebuild their self-worth as Pérez-Marco et al. found that empowerment skills were an effective resource to combat negative outcomes of abuse.[20] Treatment for perpetrators of domestic violence is less researched, but also integral to preventing relationship violence and subsequent mental health challenges. Taking into consideration social, societal and developmental contexts may be involved in methods to address high levels of violence exhibited by abusers as well as equitable access to treatment.[21,22]

Dating violence and abuse result in devastating impacts on victims' mental health, inflicting trauma that may never fully fade without proper intervention. By amplifying awareness, education, and access to mental health resources, society can stand against the silent scars left by dating violence and empower survivors on their journey toward recovery.

If one is experiencing any form of abuse or mental health challenges due to a relationship, please reach out to a licensed mental health professional (e.g., a psychotherapist, psychologist or psychiatrist) for guidance and support.

Contributed by: Phoebe Elliott

Editor: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D.

References

1 National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. National Statistics. https://ncadv.org/STATISTICS#:~:text=NATIONAL%20STATISTICS&text=On%20average%2C%20nearly%2020%20people,10%20million%20women%20and%20men.

2 Washington University in St. Louis. (2023). What is Relationship and Dating Violence? https://students.wustl.edu/relationship-dating-violence/

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Liz Claiborne Inc and The Family Fund. Teen Dating Abuse 2009 Key Topline Findings. http://nomore.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/teen_dating_abuse_2009_key_topline_findings-1.pdf

6 Piolanti, A., Waller, F., Schmid, I. E., & Foran, H. M. (2023). Long-term Adverse Outcomes Associated With Teen Dating Violence: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics, 151(6), e2022059654. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-059654

7 Pérez-Marco, A., Soares, P., Davó-Blanes, M. C., & Vives-Cases, C. (2020). Identifying Types of Dating Violence and Protective Factors among Adolescents in Spain: A Qualitative Analysis of Lights4Violence Materials. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(7), 2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072443

8 Ibid.

9 Polanti et al. (2023)

10 Malik, M., Munir, N., Ghani, M. U., & Ahmad, N. (2021). Domestic violence and its relationship with depression, anxiety and quality of life: A hidden dilemma of Pakistani women. Pakistan journal of medical sciences, 37(1), 191–194. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.37.1.2893

11 Ibid.

12 Telloian, C. (2023, March 23). What Are the Effects of Emotional Abuse? https://psychcentral.com/health/effects-of-emotional-abuse#relationship-impacts

13 PTSDuk. (2023). Causes of PTSD: Domestic Abuse. https://www.ptsduk.org/what-is-ptsd/causes-of-ptsd/domestic-abuse/

14 Ibid.

15 De Sousa, D., Paradis, A., Fernet, M., Couture, S., & Fortin, A. (2023). "I felt imprisoned": A qualitative exploration of controlling behaviors in adolescent and emerging adult dating relationships. Journal of adolescence, 95(5), 907–921. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12163

16 Guy, S. (2020, October 19). When Love is Blind: What Teens Don’t See in an Abusive Relationship. https://www.genesisshelter.org/when-love-is-blind-what-teens-dont-see-in-an-abusive-relationship/

17 Cleveland Clinic. (2022, February 14). Stockholm Syndrome. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22387-stockholm-syndrome

18 Karakurt, G., Koç, E., Katta, P., Jones, N., & Bolen, S. D. (2022). Treatments for Female Victims of Intimate Partner Violence: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 793021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.793021

19 Ibid.

20 Pérez-Marco, et al. (2020)

21 Oğuztüzün, Ç., Koyutürk, M., & Karakurt, G. (2023). Characterizing Disparities in the Treatment of Intimate Partner Violence. AMIA Joint Summits on Translational Science proceedings. AMIA Joint Summits on Translational Science, 2023, 408–417.

22 Wexler D. B. (1999). The broken mirror. A self psychological treatment perspective for relationship violence. The Journal of psychotherapy practice and research, 8(2), 129–141.