Understanding Waves of Grief

Grief has been described as “the conflicting feeling caused by the end of or change in a familiar pattern of behavior.”[1] Emotions brought on by the experience of a significant loss can be turbulent; and in some cases, can feel like a wave from the ocean as they build and release into one’s reality. Briana MacWilliam (2017) notes, “Some things you never get over, you just learn to carry them.” It is difficult to say whether grief is an experience that one can be rid of, or if it is better understood as something that can be learned to cope with overtime. It is possible for one to feel they have gotten over a loss, and for grief to then show up again causing more unexpected emotional turbulence. Grief can sometimes create the illusion that one cannot move forward, or that one’s life is irreparably damaged. While it is true that one may never be the same, there are ways to grow after experiencing a traumatic loss.[2]

A loss can take on various forms: the death of a loved one, a romantic heartbreak, loss of a job, loss of a friend, death of a pet, and so on. One cannot control the rain that ruined the picnic, the missed flight that cost a promotion, the fall-out of a romantic relationship, or the cancer that took a loved one’s life. However, one is able to control how to move forward from such experiences. A decision must be made on how to shape one’s future experiences in a positive manner instead of succumbing to horrible events and allowing them to control future events. “Easier said than done,” one might say - and they would be right. However, the initial choice of moving forward is one of the most imperative moments in shaping one’s reality. Dwelling on feelings of heartache is not always a healthy way of honoring the dead or the lost; it can also be a form of self-punishment. MacWilliam notes, “The work of grief is the work of growth.”[3] Tolle (2004) adds that, “It is a choice between falling into a victimized identity or ‘discovering grace’ on the opposite side of helplessness and surrender.”[4]

After experiencing a loss, there are many ways that one can be reminded of their grief (e.g., hearing a song, the anniversary of a loss, and even seeing something small that reminds you of the person or the loss). Such triggers can make it difficult to maneuver through the five common phases of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.[5] Being reminded about one’s grief can create a feeling of one’s heart being enclosed in a vacuum seal, provoking anxiety about the onset of difficult memories. Various approaches can be used to cope with such emotions and triggers. However, one must first understand common myths of the nature of grief and how societal factors play into one’s experience with grief.

Common Myths of Grief

In an attempt to cope with grief, society has developed myths about the appropriate approaches to facing our difficult emotions. Popular phrases in the Western world can have a negative impact on the process of growth after experiencing loss. MacWilliam notes a few common phrases associated with myths surrounding how one should experience grief:[6]

Don’t Feel Bad

Replace the Loss

Grieve Alone

Just Give it Time

Be Strong for Others

Keep Busy

The issue with these common myths is that they involve repressing and disregarding feelings of pain, which in turn, can become “stuck” in one’s body, leading to significant diagnoses such as anxiety and depression.[7] Grief is a normal and natural reaction to any kind of loss. Therefore, one should embrace the waves of emotion that are associated with traumatic loss.[8] To embrace grief, one may try:

Feeling as Bad as You Do

Not Replacing the Loss

Finding Others That Share Your Pain

Taking One’s Time to Acknowledge the Loss

Letting Others Take Care of Themselves

Not Burning Out on Distractions

Grieving is Not Selfish

It is common for feelings of grief to become internalized, creating a sense of shame and selfishness in an individual. However, the experience of grief is not selfish, nor is it selfish to move on and experience feelings of joy again. The way in which one reacts to grief is generally in-line with one’s personality traits. For example, if one is quiet by nature, grief might be expressed more quietly and internally. Introverts, as such, are likely to hear encouragement from others to express their grief more outwardly when it happens. Conversely, individuals that are more naturally outgoing might express grief more openly; prompting responses from some people to keep emotions inside.[9] Social acceptance, or the lack thereof, can help or hinder one’s experience of grief. It is important for each individual to figure out what level of expression works best for them on their journey of self-growth. To find what works best for you, there are resources available such as self-help groups. These groups can help one to acknowledge the myths surrounding grief while providing a safe place to express oneself.[10]

Radical Acceptance

Radical acceptance is a technique derived from Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), that encourages one to look at the reality of a situation without judgment or distortion.[11] Instead of idealizing a scenario to be what you want it to be, radical acceptance means understanding that we are all doing the best we can. The practice of radical acceptance validates one’s emotions, thoughts, and actions.[12] Validating emotions such as loneliness and fear can help to change one’s perspective on a situation and in turn the experience of a challenging situation such as grief. Brian Therialut, a writer who lost his wife to cancer, notes that “Grief loses its power when it is radically accepted in the moment.”[13] By normalizing experiences such as grief, one can find coping mechanisms to deal with the stress and heavy emotions. Simple radical acceptance inquiry has been known to significantly improve coping and reduce suffering.[14] Even one’s inquiry into simple radical acceptance has been found to significantly improve coping and reduce suffering.

A study by Görg et al. (2017) measured the success of radical acceptance when treating trauma-related memories and associated emotions. Shame, guilt, disgust, distress, and fear were all found to significantly decrease from the start to the end of radical acceptance therapy. Radical acceptance has been found to be successful in treating emotions associated with trauma because it focuses on how to reduce the avoidance of memories.[15] Specifically, DBT encourages individuals to accept past traumatic events, painful memories of those events, and emotions about having experienced the events. In the study by Görg et al. (2017) the DBT treatment approaches utilized training for self-esteem, mindfulness, psychoeducation, and music or art therapy. In the end, radical acceptance functioned as a way to cope with traumatic or painful memories.

Practice & Implementation

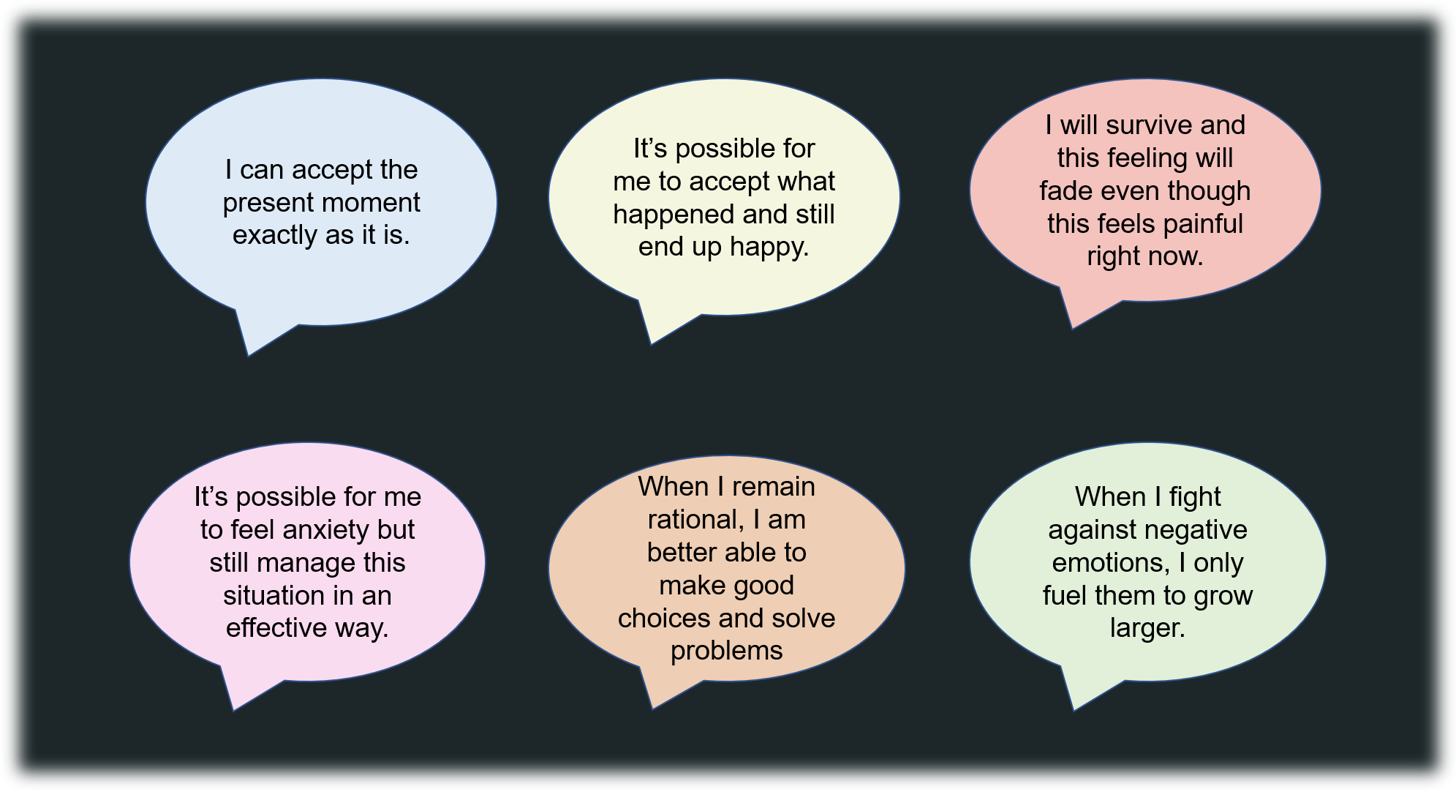

There are various approaches to implementing radical acceptance into one’s reality. For instance, when acceptance of a situation feels almost impossible, Cuncic (2022) offers some coping statements to help one practice radical acceptance:[16]

Image Source: Tori Steffen

Searching for beauty in a difficult situation can replace suffering with feelings of gratitude. Focusing on the sound of rain hitting the roof, the smell of burning firewood, or the taste of your favorite beverage can foster love and compassion. The more beauty one seeks out, the more likely one is to disengage in self-criticism.[17] Another approach is to outsmart your inner critic by discrediting self-doubt. Self-criticism can help one to grow, but it can also be self-destructive in that your perspective is clouded by a negative filter. One way to bring positivity into the picture when you are feeling self-critical is to think of a loved one and write a letter to yourself from their perspective. People often judge themselves too harshly, and rarely look at themselves from others’ perspectives. Taking the viewpoint of a loved one towards oneself can remind one of what they should admire about themselves.[18]

Additional approaches to implementing radical acceptance include embracing vulnerability and giving yourself the love you are searching for.[19] After expressing oneself in a vulnerable manner, it is likely that one can feel they have shared too much of themself. The reality of the situation is that the expresser is the one who reflects and cringes the most after being “too vulnerable”. Those that witnessed someone else being vulnerable are likely to feel closer to said person, and this connection is what fosters a sense of love for others.[20] To give yourself the love that you are searching for in others is to empower your independence and self-esteem.

Radical acceptance is often not an easy practice to implement in reality due to the nature of heavy emotions associated with grief. Radically accepting a situation does not mean that you agree with what is happening or what has occurred. Rather, it creates a chance to feel hopeful for the future because one can stop fighting the reality of a situation.[21] Lack of acceptance in a tough situation is normal and many have experienced the trials and tribulations of grief.

Another way to practice radical acceptance includes paying attention to triggers and noticing when acceptance is difficult. Imagining what reality would look like if you accepted the situation can be a great first step in practicing radical acceptance.[22] Ultimately, accepting the fact that life can still be worthwhile even when experiencing pain will help one to navigate the ocean of grief. Moreover, committing to the practice of radical acceptance when feeling resistance will help it to become more second-natured to an individual dealing with grief.

When feelings of depression and anxiety related to grief are chronic and impacting everyday life, steps should be taken to reduce such negative experiences by contacting a licensed mental health professional for further guidance.

Contributed by: Tori Steffen

Editor: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D.

REFERENCES

1 James, J. and Friedman, R. (2009) The Grief Recovery Handbook: The Action Program for Moving beyond Death, Divorce, and Other Losses including Health, Career, and Faith. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

2 Briana MacWilliam. (2017). Complicated Grief, Attachment, and Art Therapy : Theory, Treatment, and 14 Ready-to-Use Protocols. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

3 Ibid.

4 Tolle, E. (2004) The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment. Novato, Canada: Namaste Publishing.

5 Kessler, D., and Kubler Ross, E. (2022). Five stages of grief by Elisabeth Kubler Ross and David Kessler. Grief.com. https://grief.com/the-five-stages-of-grief/#:~:text=The%20five%20stages%2C%20denial%2C%20anger,some%20linear%20timeline%20in%20grief.

6 MacWilliam (2017)

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Tapper, M. L. (2016). Radical acceptance. MedSurg Nursing, 25(1), S1.

12 Ibid.

13 Theriault, B. (2012). Radical Acceptance A Nondual Psychology Approach to Grief and Loss. International Journal of Mental Health & Addiction, 10(3), 354–367.

14 Tapper (2016)

15 Goerg, N., Priebe, K., Bohnke, J. R., Steil, R., Dyer, A. S., & Kleindienst, N. (2017). Trauma-related emotions and radical acceptance in dialectical behavior therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder after childhood sexual abuse. BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER AND EMOTION DYSREGULATION, 4, UNSP 15.

16 Cuncic, A. (2022). What is radical acceptance? Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-radical-acceptance-5120614

17 Try these practices daily for radical self-acceptance. (2019). Yoga Journal, 311, 20.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Cuncic (2022)

22 Ibid.