- To seek treatment, please refer to this list of DBT providers.

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT)

Overview

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based treatment evolved and developed by Psychologist Marsha Linehan in 1993 to treat people with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD).[1] Linehan aimed to target suicidal behavior with this treatment and ended up developing a comprehensive, evidence-based, cognitive-behavioral treatment for BPD. It is currently the only empirically supported treatment for BPD and has also been shown to improve outcomes in other psychiatric disorders such as substance use disorders, mood disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and eating disorders.[2]

According to Chapman (2006), DBT treatment involves weekly individual sessions, weekly group skills training sessions, phone coaching, and therapist consultation meetings. The combination of these many facets of the treatment bolster its efficacy, as there are multiple different settings for learning, discussion, and practice. One notable aspect of DBT is its dialectical philosophy; dialectical frameworks are defined by the view that reality consists of opposing forces that can be true at the same time. For example, life can be excruciatingly difficult, and full of beauty at the same time. Another example would be that everyone is trying their best, and everyone can always do better. Linehan’s overarching goal was to help others create lives they find worth living.[3]

Borderline personality disorder is one of the most stigmatized mental disorders, and people with the condition tend to experience extreme difficulties managing relationships, conflict, stress, self-image, and other areas of functioning.[4] According to Carmel et al., (2014), patients with BPD tend to place a disproportionately high financial burden on systems of care because of how many behavioral health services they seek. The authors also argue that the growth of the evidence-based practice movement has led to an increased need for empirical support that delineates concrete linkages between research and clinical practice.[5]

There are four core modules that comprise DBT’s comprehensive approach:

Mindfulness

Distress Tolerance

Emotion Regulation

Interpersonal Effectiveness

Mindfulness skills involve the practice of observing reality without judgment and accepting thoughts and emotions as distinct entities from the self. This skill is essential because without knowing one’s thoughts and feelings, it is much more difficult to proceed to implement other skills that address those thoughts and feelings. Mindfulness serves as the bedrock for DBT, where patients acquire the ability to recognize and acknowledge inner turmoil, and can then follow up with additional skills. Its centrality to DBT is adapted from Zen Buddhism, as Linehan believed in the power and philosophy of meditation practices.[6,7]

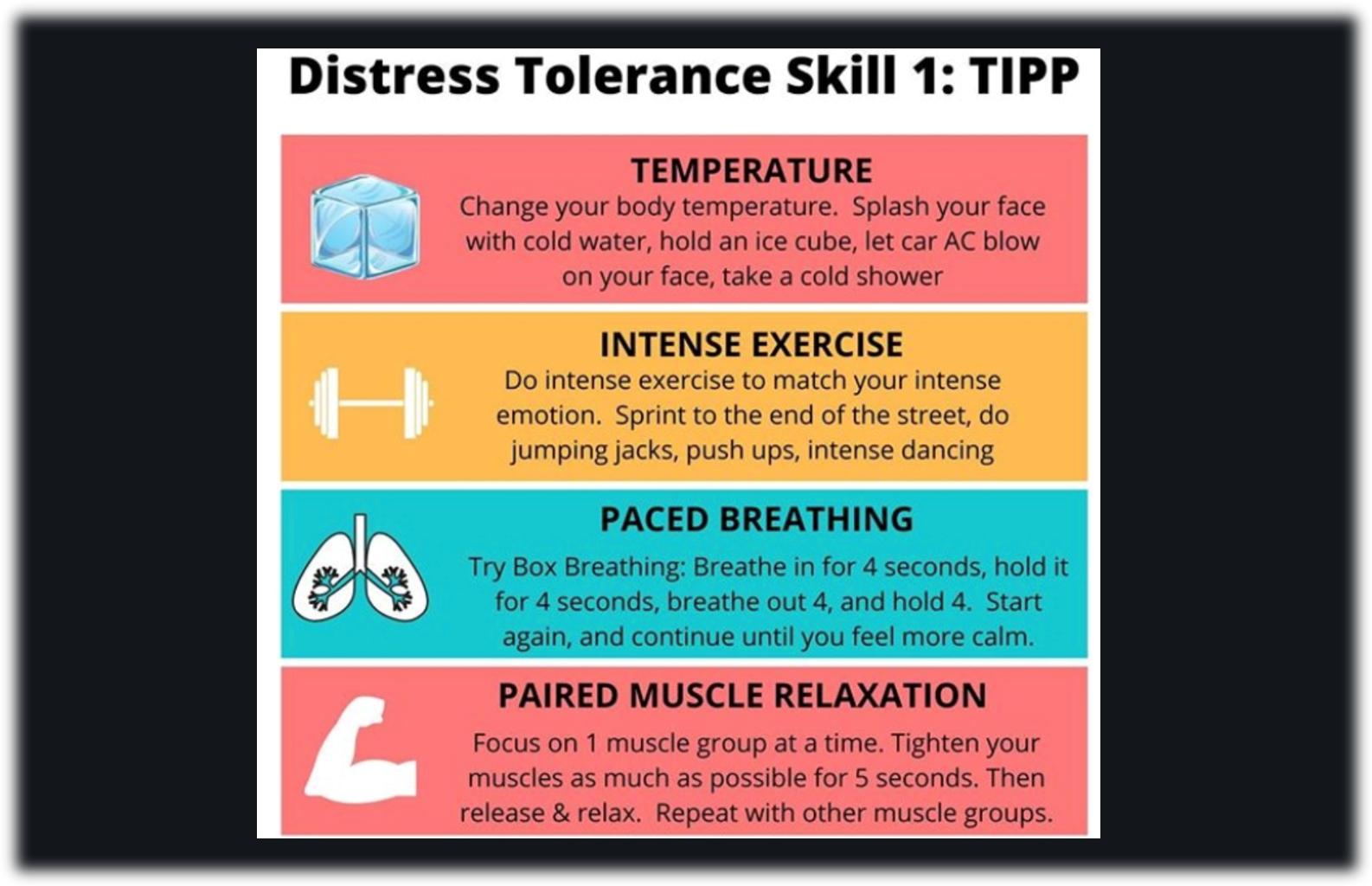

Distress Tolerance skills provide a patient the knowledge of how to progress through a severely distressing moment or crisis. One skill is called TIPP, and through temperature moderation, intense exercise, paced breathing, or paired muscle relaxation, a person can trigger their parasympathetic nervous system to activate.[8] The activation of the parasympathetic nervous system signals safety and moves one out of fight-or-flight into a state of rest and digestion. Other skills in this module similarly guide a person from panic toward calmness.

Figure 1: DBT worksheet for the TIPP skill

Note: This figure was produced by Green, J. (n.d.)[9]

Emotion Regulation skills help people understand the functions of different emotions and their accompanying action urges.[10] Since most-- if not all-- emotions exhibit an action urge, it is important to familiarize oneself with one’s action urges and to investigate the impact of these options. One DBT Emotion Regulation skill is designed specifically to target action urges and is called Opposite Action. This skill is useful for making an emotion go away or become less uncomfortable, and works when someone does the opposite action to their emotion. For example, if someone feels depressed and unmotivated to leave bed, they may use the Opposite Action skill to brush their teeth and make breakfast.

Figure 2: Emotions and their opposite actions

Note: This figure was produced by DBT tools[11]

Finally, interpersonal effectiveness teaches skills for smoother and clearer communication and confrontation. There are skills, like DEAR MAN, that walk patients through a step-by-step process of having difficult conversations and asserting one’s needs.[12]

Figure 3: Steps for using the DEAR MAN skill

Note: This figure was produced by Lamm, J. (2019)[13]

Outside of the patient’s experience of the curriculum, therapists administering DBT are also expected to participate in weekly consultation meetings with other therapists and supervisors. Without the component of regular case consultation, a therapist is not technically implementing comprehensive DBT.[14] The combination of practical and feasible skills, homework for practice, group support, access to the therapist outside of sessions, and therapist consultation all work together to ensure that a patient is progressing with structured consistency and multiple professional perspectives.

Applications of Dialectical Behavior Therapy

Below is a non-exhaustive list of some of the uses for DBT:

Reduce suicidality and suicidal behavior

Reduce non-suicidal self injury

Accept the past, present, and future

Learn new and effective behaviors to replace maladaptive ones

Increase and improve mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, emotion regulation, and distress tolerance

Address therapy interfering behaviors (e.g. missing treatment, substance use, unemployment)

Expand a person’s ability to experience a full range of emotions

Learn to tolerate distress without impulsivity or destruction

Build a life worth living; discover personal values and life goals

Mental health disorders that may improve with DBT:

Borderline Personality Disorder

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Patient Experience

The patient experience of DBT includes individual therapy, group therapy, and phone coaching. Each of these three components work together to ensure a person is continuing to build therapeutic skills and provide different types of support.

Individual therapy is for individualized discussion about how DBT skills can be better applied to one’s personal needs and lifestyle. The one-on-one setting allows for vulnerable, in-depth, very specific collaboration about where and how one can be using different skills outside of therapy. Homework is an essential part of DBT and patients typically fill out daily “diary cards” to track thoughts, emotions, urges, and behaviors. Skills can also be tracked on the cards to determine which ones a person is using and how helpful they are.[15] Weekly individual sessions provide a space for homework discussion that may not be fitting for group settings.

Figure 3: Example of a Diary Card

Note: These figures were produced by Beaches Therapy[16]

Group therapy is typically where people learn and discuss new skills, share their experiences practicing skills, and receive feedback on homework from group leaders and peers. Blackford & Love (2011) found a positive correlation between group skills training attendance and symptom reduction, which was consistent with a naturalistic study by Harley et al. (2007).[17,18] Blackford & Love also demonstrated that moderately-trained clinicians could successfully execute DBT skills training groups in community mental health settings, which would increase the accessibility of cost effective treatment.

Phone coaching is where a person can call their therapist during the week and receive in-the-moment coaching for skill use. The rationale for between-session telephone coaching is based on the fact that suicidal people often need more frequent therapy than weekly sessions. It is an extra source of support for desperate moments and also can encourage healthy communication and social interaction by practicing phone call skills (Linehan & Wilks, 2018). For an example of how telephone coaching can reinforce skills usage, someone may try to use an Emotion Regulation skill before delivering an important work presentation and not experience any symptom relief; phone coaching could be useful for troubleshooting and trying different combinations of skills or receiving guidance about executing the skill more effectively.

Additionally, DBT can be divided into four stages of treatment:

First, the client feels out of control and has to move toward achieving behavioral control. This stage is where suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury are targeted.

The client next moves from a state of desperation toward full emotional experiencing. Before DBT treatment, patients often have an inhibited emotional experience due to past trauma and invalidation.

In the third stage, the client defines life goals, builds self-respect, and finds peace and happiness. In this stage, the goal is to lead a life of ordinary happiness and unhappiness.

While some clients complete treatment in the third stage, others need the fourth stage of finding deeper meaning, if ordinary happiness and unhappiness fail to meet a further goal of connectedness or fulfillment. [19]

Evidence Base for DBT

As of 2014, there were eleven controlled trials of DBT that showed effective reduction in suicidal behavior and inpatient admissions, among other key outcomes.[20-27] Generally, these studies provide evidence that self-injurious, substance abuse, and suicidal behaviors decrease significantly with DBT. In a study by Priebe and colleagues (2012), the researchers found that DBT was more effective than control conditions, such as individual psychotherapy, validation therapy for substance abuse, or community treatment. They propose that DBT is most impactful for addressing high-risk behavior rather than broad clinical symptoms, which is congruent with other studies that criticize the reputation of DBT.[28,29]

There are numerous published findings that provide empirical evidence of DBT’s effectiveness for BPD through randomized controlled trials. However, the generalizability of this treatment for routine health care has not yet been fully elucidated.[30] In a study conducted by Stiglmayr et al. (2014), DBT was implemented in Germany via a routine health care situation. Out of 78 patients who started the study, 47 of them completed one year of treatment. Patients experienced significant improvement regarding self-injury, number of inpatient hospital stays, and severity of borderline personality disorder symptoms. In fact, after one year of treatment, 77% of patients no longer met diagnostic criteria for BPD. Under routine mental health care conditions in Germany, DBT led to positive and significant changes that corresponded with efficacy findings of previous studies that used randomized controlled trials. This study provides evidence that DBT’s effectiveness can be generalizable to the public and is not dependent upon the presence of experimental lab conditions.[31] Rather, it can improve symptom severity in real life mental health care settings. Additional studies like this one that model the applicability of DBT in non-experimental conditions would help clinicians understand how to facilitate treatment in a wide variety of contexts.

One study by Schaich et al. (2021) investigated how patients with BPD experience the Distress Tolerance Skill portion of DBT. In general, they found that patients experienced immediate reduction of distress, prevention of self-injurious and suicidal behavior, and increased functioning. They perceived Distress Tolerance skills as tools to handle challenges and crises which increased their feelings of stability, safety, and confidence. Despite these benefits, they also experienced the training and implementation of these skills as overwhelming and difficult. The authors reflect that these skills can be powerfully helpful if mastered, but also acknowledge the importance of addressing tension and reluctance between therapist and client through this process.[32]

Limitations and Future Research

DBT has the most supportive evidence and has been empirically tested more than any other treatment for BPD. While there is substantial evidence demonstrating the efficacy of DBT for reducing BPD symptoms, there is also a notable amount of inconclusive evidence.[33] Bendit (2013) finds that when other treatments are compared to DBT, they perform the same in outcome measures. He concludes that the evidence in support of DBT is not as strong as its reputation, and he mainly seeks to expand people’s perceptions about treatment options for BPD.

In order to bolster DBT’s influence, there could be more research on its application for psychiatric disorders other than BPD. Given that DBT has been implemented and assessed for less than 30 years, there is considerable empirical evidence in support of its efficacy for not only borderline personality disorder, but also mood disorders, eating disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Lynch et al., 2003). While some studies demonstrate its applicability for other mental health conditions, most existing research identifies advantages of this treatment for those with BPD. Understanding the exact mechanisms of how this treatment improves symptoms of mood disorders would allow future therapeutic modalities to replicate and expand on the specific aspects that help alleviate suffering. Related to BPD treatment broadly, it would be helpful for therapeutic services like DBT to become more widely accessible, especially financially.

Furthermore, Toms et al. (2019) write that DBT efficacy has mostly been assessed in Western and outpatient mental health service contexts. They also mention how large reviews of DBT rely on published literature, which usually reflect a bias toward positive results. There is also still a need to implement and study DBT within marginalized and high risk populations, such as cultural minority groups. Their paper also identifies how reports of DBT implementation largely depend on self-reports of success, and collect data retrospectively. In one instance, Toms et al. (2019) found that samples may not have been representative, as the response rate was approximately 14%.[34] Therefore, some of the research touting overwhelming success may only illustrate the experiences of a minority of people in DBT treatment. There is certainly work still to be done in terms of determining DBT’s generalizability to non-Western cultures and other psychiatric conditions.

Despite the limited number of published studies that attest to the validity of treatment outcomes in non-randomized, non-controlled settings, there is still evidence demonstrating its efficacy in real world health care systems.[35] The fact that DBT has been demonstrably effective in community mental health agencies is important. Access to mental health treatment is often largely dependent on a person’s financial means, and since BPD tends to require substantial support and therapy, it is critical that people can afford the help they need. Since DBT is partly based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (which is often heralded as the gold standard for psychotherapy), it is likely that DBT will continue to garner supportive research as the field of psychology continues on its quest for evidence-based and empirically-supported practices.

Contributed by: Maya Hsu

Editor: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D.

References

1 Dardashti, N. (2016). The history & benefits of dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT). Manhattan Psychology Group. https://manhattanpsychologygroup.com/dbt-dialectical-behavior-therapy-nyc/

2 May, J. M., Richardi, T. M., & Barth, K. S. (2016). Dialectical behavior therapy as treatment for borderline personality disorder. The mental health clinician. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6007584/

3 Chapman A. L. (2006). Dialectical behavior therapy: current indications and unique elements. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 3(9), 62–68.

4 Greenstein, L. (2017). Treating borderline personality disorder. NAMI. Retrieved from https://www.nami.org/Blogs/NAMI-Blog/June-2017/Treating-Borderline-Personality-Disorder

5 Carmel, A., Rose, M. L., & Fruzzetti, A. E. (2014). Barriers and solutions to implementing dialectical behavior therapy in a public behavioral health system. Administration and policy in mental health, 41(5), 608–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0504-6

6 Robins, C. (2002). Zen principles and mindfulness practice in dialectical behavior therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 9(1), 50-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1077-7229(02)80040-2

7 Huppertz M. (2003). The relevance of zen-buddhism for dialectic-behavioral therapy. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, medizinische Psychologie, 53(9-10), 376–383. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2003-42174

8 Linehan, M. M., & Wilks, C. R. (2018). The course and evolution of dialectical behavior therapy. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 69(2), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2015.69.2.97

9 Green, J. (n.d.) TIPP skill. The love therapist. https://jordanandrea.com/

10 What are DBT emotion regulation skills? Sunrise Residential Treatment Center. (2017). https://sunrisertc.com/dbt-emotion-regulation-skills/

11 Linehan, M. (n.d.). Opposite action skill. Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) Tools. Retrieved from https://dbt.tools/emotional_regulation/opposite-action.php

12 Moore, K. E., Folk, J. B., Boren, E. A., Tangney, J. P., Fischer, S., & Schrader, S. W. (2018). Pilot study of a brief dialectical behavior therapy skills group for jail inmates. Psychological services, 15(1), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000105

13 Lamm, J. (2019). DEAR MAN: Learn efficient communication. The Mind Fool. https://themindfool.com/dear-man-steps-that-help-you-strike-efficient-communication/

14 Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. (2021). Dialectical behavior therapy. ABCT. https://www.abct.org/fact-sheets/dialectical-behavior-therapy/

15 Tartakovsky, M. (2021). What is dialectical behavior therapy, and is it right for me? Psych Central. https://psychcentral.com/lib/an-overview-of-dialectical-behavior-therapy

16 Client tools, info & forms. Beaches Therapy - DBT & Mindfulness Center. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.beachestherapy.com/resources--info.html

17 Blackford, J. U., & Love, R. (2011). Dialectical behavior therapy group skills training in a community mental health setting: a pilot study. International journal of group psychotherapy, 61(4), 645-657. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijgp.2011.61.4.645

18 Harley, R. M., Baity, M. R., Blais, M. A., & Jacobo, M. C. (2007). Use of dialectical behavior therapy skills training for borderline personality disorder in a naturalistic setting. Psychotherapy Research, 17(3), 351-358. DOI: 10.1080/10503300600830710

19 University of Washington. (n.d.). Dialectical Behavior Therapy. Behavioral Research Therapy Clinics. https://depts.washington.edu/uwbrtc/about-us/dialectical-behavior-therapy/

20 Bohus, M., Dyer, A. S., Priebe, K., Krüger, A., Kleindienst, N., Schmahl, C., Niedtfeld, I., & Steil, R. (2013). Dialectical behaviour therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder after childhood sexual abuse in patients with and without borderline personality disorder: A randomised controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82, 221-233. https://doi.org/10.1159/000348451

21 Koons, C. R., Robins, C. J., Tweed, J. L., Lynch, T. R., Gonzalez, A. M., Morse, J. Q., Bishop, G. K., Butterfield, M. I., & Bastian, L. A. (2006). Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy, 32(2), 371-390. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(01)80009-5

22 Linehan, M. M., Armstrong, H. E., Suarez, A., Allmon, D., Heard, H. L. (1991). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of general psychiatry, 48(12), 1060-1064. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003

23 Linehan, M. M., Comtois, K. A., Murray, A. M., Brown, M. Z., Gallop, R. J., Heard, H. L., Korslund, K. E., Tutek, D. A., Reynolds, S. K., & Lindenboim, N. (2006). Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of general psychiatry, 63(7), 757–766. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757

24 Linehan, M. M., Dimeff, L. A., Reynolds, S. K., Comtois, K. A., Welch, S. S., Heagerty, P., & Kivlahan, D. R. (2002). Dialectical behavior therapy versus comprehensive validation therapy plus 12-step for the treatment of opioid dependent women meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder. Drug and alcohol dependence, 67(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00011-x

25 Lynch, T. R., Morse, J. Q., Mendelson, T., & Robins, C. J. (2003). Dialectical behavior therapy for depressed older adults: a randomized pilot study. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry: official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 11(1), 33–45.

26 Telch, C. F., Agras, W. S., & Linehan, M. M. (2001). Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 69(6), 1061–1065. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1061

27 Verheul, R., Van Den Bosch, L. M., Koeter, M. W., De Ridder, M. A., Stijnen, T., & Van Den Brink, W. (2003). Dialectical behaviour therapy for women with borderline personality disorder: 12-month, randomised clinical trial in The Netherlands. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science, 182, 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.182.2.135

28 Priebe, S., Bhatti, N., Barnicot, K., Bremner, S., Gaglia, A., Katsakou, C., Molosankwe, I., McCrone, P., & Zinkler, M. (2012). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of dialectical behaviour therapy for self-harming patients with personality disorder: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 81(6), 356-365. https://doi.org/10.1159/000338897

29 Toms, G., Williams, L., Rycroft-Malone, J., Swales, M., & Feigenbaum, J. (2019). The development and theoretical application of an implementation framework for dialectical behavior therapy: a critical literature review. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-019-0102-7

30 Flynn, D., Kells, M., Joyce, M., Suarez, C., & Gillespie, C. (2018). Dialectical behaviour therapy for treating adults and adolescents with emotional and behavioural dysregulation: study protocol of a coordinated implementation in a publicly funded health service. BMC Psychiatry, 18(51). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1627-9

31 Stiglmayr, C., Stecher-Mohr, J., Wagner, T., Meiβner, J., Spretz, D., Steffens, C., Roepke, S., Fydrich, T., Salbach-Andrae, H., Schulze, J., & Renneberg, B. (2014). Effectiveness of dialectic behavioral therapy in routine outpatient care: the Berlin Borderline Study. Borderline personality disorder and emotion dysregulation, 1, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/2051-6673-1-20

32 Schaich, A., Braakmann, D., Rogg, M., Meine, C., Ambrosch, J., Assmann, N., Borgwardt, S., Schweiger, U., & Fassbinder, E. (2021). How do patients with borderline personality disorder experience Distress Tolerance Skills in the context of dialectical behavioral therapy?-A qualitative study. PloS one, 16(6). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252403

33 Bendit, N. (2013). Reputation and science: examining the effectiveness of DBT in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Australasian Psychiatry, 22(2), 144-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856213510959

34 Sharma, B., Dunlop, B. W., Ninan, P. T., & Bradley, R. (2007). Use of dialectical behavior therapy in borderline personality disorder: a view from residency. Academic Psychiatry, 31, 218-224. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.31.3.218

35 Flynn, D., Kells, M., & Joyce, M. (2021). Dialectical behavior therapy: implementation of an evidence-based intervention for borderline personality disorder in public health systems. Current Opinion in Psychology, 37, 152-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.01.002