The Unrecognized Grief

Grief is an often overwhelming emotion commonly associated with losing a loved one or a personal tragedy. But, what if grief arises from a dream that never materializes or when life continually falls short of expectations? Nonfinite grief occurs when one mourns for what was never realized as opposed to grieving something that has been lost.[1] In terms of duration, nonfinite grief is a continuing presence of loss that may be physical, psychological, and/or emotional.[2] In a world where life's disappointments and unfulfilled hopes can be devastating, understanding nonfinite grief can help people process and comprehend the spectrum of human emotional experiences.[3]

Assumptive World

Throughout a person's lifetime, their early experiences shape their beliefs, expectations, and assumptions about how the world operates. These foundations are influenced by various factors such as culture, people's behaviors, upbringing, and other elements, collectively called the "assumptive world".[4] Conversely, the shattered assumptions theory, introduced by Janoff-Bulman in the context of traumatic experiences, explains that individuals rely on these assumptions about the world and themselves to maintain healthy human functioning.[5] Edmondson et al. (2011) explains that without these assumptions, individuals may face a breakdown of their life narrative and a loss of self-identity, as described in the shattered assumptions theory.[6] The predictable worldview's function is to provide individuals with a sense of purpose, self-worth, and the illusion of invulnerability.[7]

Conversely, when one’s assumptive world undergoes severe disruptions, individuals can experience nonfinite grief. This grief can manifest from different types of life experiences, as demonstrated by the following examples:

Physical: An athlete has been diligently preparing for a life-changing game. Due to a recent injury, they were rendered ineligible to participate in that pivotal game and left devastated.

Psychological: An individual tirelessly worked towards a promotion at their job. They were passed over, leaving them with a deep sense of disappointment.

Emotional: An individual longs for the day they exchange vows with their long term partner. However, as the years pass, they find themselves single and the dream of marriage seemingly slipping away.

Recognizing the Grief

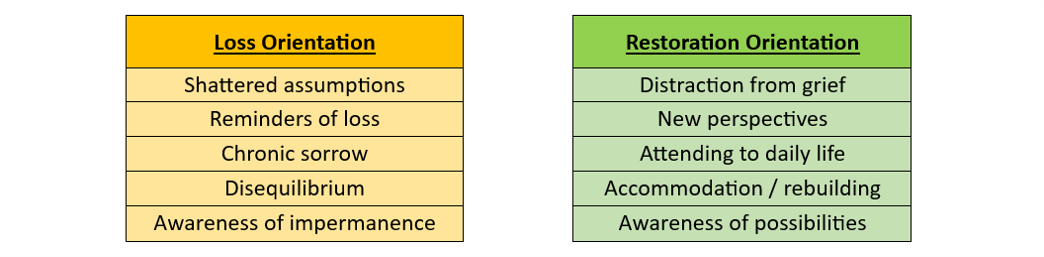

Grief, when it falls outside of societal norms, can be hard to identify. The Dual Process Model for Non-Death Loss and Grief displays some of the everyday experiences of an individual oscillating between loss orientation and restoration orientation.[8] Wang et al. (2021) explains how loss orientation refers to the focus on coping with the loss itself whereas restoration orientation is a coping strategy that focuses on emotional recovery.[9]

In the Dual Process Model (as shown below) people oscillate between two types of orientation during their every day lives.[10]

In order to try to recognize one’s grief, the following three main factors separate nonfinite grief experiences from grief caused by death:[11]

The loss causes a persistent feeling of despair and emptiness from the reality shaped by their previous expectations with their envisioned future.

The loss is due to an inability to meet developmental expectations.

The loss is intangible, such as a loss of one’s hopes or ideals related to what the individual believes should have, could have, or would have been.

Furthermore, individuals grappling with nonfinite loss, such as erosion of long-cherished hopes and aspirations, often contend with persistent uncertainty regarding what the future holds.[12] A pervasive feeling of helplessness and powerlessness accompanies this ongoing loss, which is often met with little recognition or acknowledgment by others.[13]

Finding new meaning to life

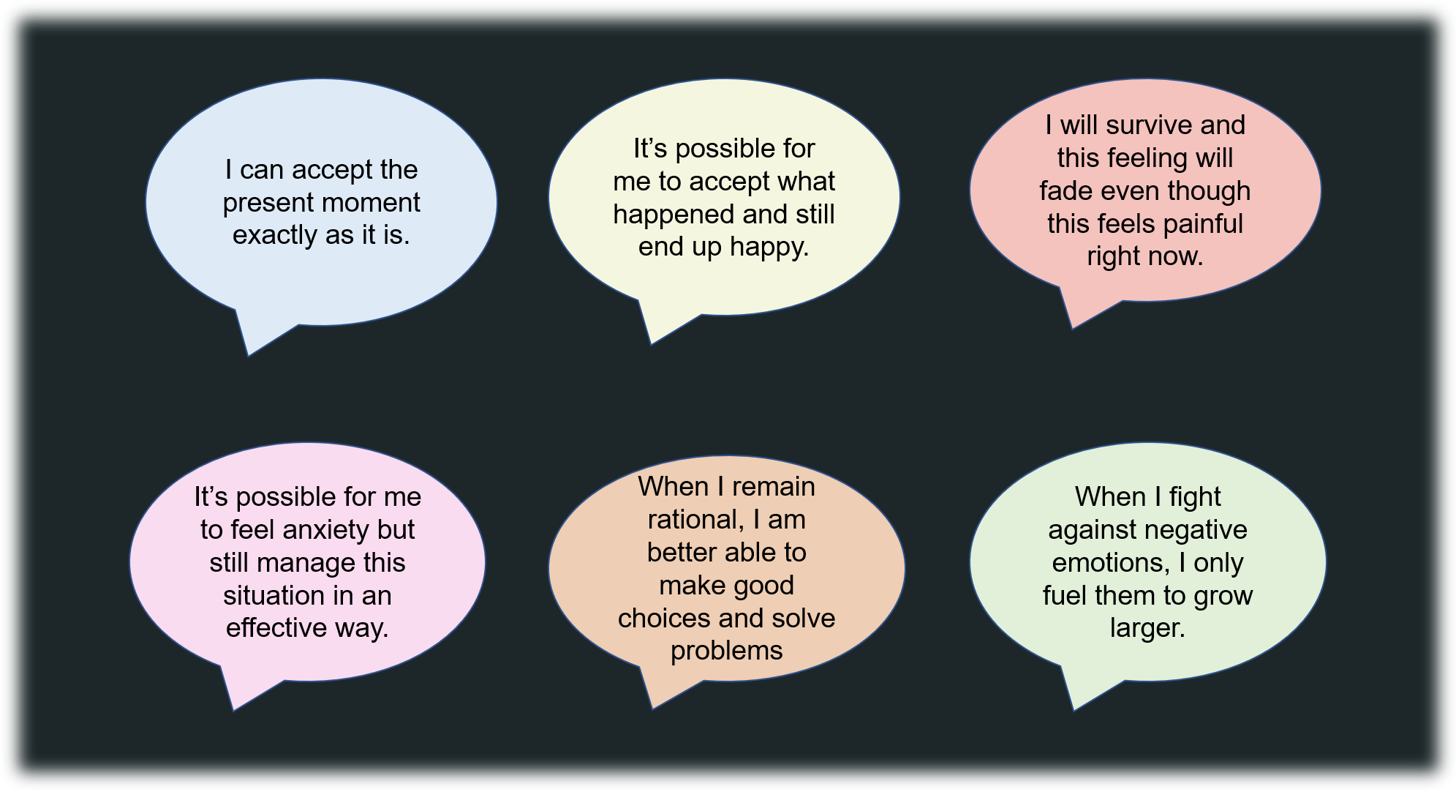

Discovering new meaning to life can feel incredibly challenging especially when initial hopes and expectations were high. Amidst the grieving process, acceptance is more about recognizing that the new reality is permanent rather than merely adjusting.[14] Furthermore, acceptance includes taking a non-judgemental attitude towards oneself rather than labeling the grieving as a negative or positive experience.[15] When grappling with the complexities of grief, specialized therapy such as Complicated Grief Therapy (CGT) can help. This therapy is designed to address intense yearning, persistent longing, intrusive thoughts, and the acceptance of the reality of loss.[16] In addition to alleviating these specific symptoms, CGT also emphasizes the importance of personal growth, nurturing relationships as part of the healing process, and is based on attachment theory.[17] CGT with elements of cognitive-behavioral principles has been shown the most promise for individuals.[18]

An individual in CGT would cover seven core themes spanning over 16 sessions, including:[19]

Understanding and accepting grief

Managing painful emotions

Planning for a meaningful future

Strengthening ongoing relationships

Telling the story of the loss

Learning to live with reminders

Establishing an enduring connection with memories of the loss

Although 16 sessions is recommended, CGT is a flexible program.

Another valuable approach for addressing grief is Acceptance and Commitment therapy (ACT).[20] Similarly to CGT, ACT uses core themes for individuals to work through their loss and life transitions including:[21]

Acceptance or willing to experience negative emotions or thoughts

Cognitive defusion

Contact with the present moment

Self as context

Values

Committed Action

Malmir et al. (2017) explored the effectiveness of ACT for grieving individuals between the ages of 20 and 40 who were experiencing a range of symptoms, including anxiety, shortness of breath, illusion, and sleep disturbances.[22] The before and after outcomes were evaluated using a questionnaire designed to gauge the participant’s level of hope and anxiety.[23] The results of ACT therapy showed a significant reduction in symptoms among the eleven women and six men who received therapy compared to the ten women and seven men who did not.[24] The effectiveness of this modality in terms of healing from grief comes from increased cognitive flexibility, which is the main component of ACT.

If you or someone you know are experiencing nonfinite grief and loss that is impacting daily life and overall well-being, please reach out to a licensed mental health professional (e.g., a psychotherapist, psychologist or psychiatrist) for additional guidance and support.

Contributed by: Kelly Valentin

Editor: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D.

REFERENCES

1 Bruce, E. J., & Schultz, C. L. (2001). Nonfinite Loss and Grief: a psychoeducational approach. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL8601025M/Nonfinite_Loss_and_Grief

2 Neimeyer, R. A., Harris, D. L., Winokuer, H. R., & Thornton, G. (2021). Grief and bereavement in contemporary society: Bridging Research and Practice. Routledge.

3 Harris, D. L. (2011). Counting our losses: Reflecting on Change, Loss, and Transition in Everyday Life. Routledge.

4 Parkes, C. M. (1971). Psycho-social transitions: A field for study. Social Science & Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-7856(71)90091-6

5 Edmondson, D., Chaudoir, S. R., Mills, M. A., Park, C. L., Holub, J., & Bartkowiak, J. (2011). From shattered assumptions to weakened worldviews: trauma symptoms signal anxiety buffer disruption. Journal of Loss & Trauma. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2011.572030

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Harris (2011)

9 Wang, W., Song, S., Chen, X., & Yuan, W. L. (2021). When learning goal orientation leads to learning from failure: the roles of negative emotion coping orientation and positive grieving. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.608256

10 Stroebe, W., Schut, H., & Stroebe, M. S. (2005). Grief work, disclosure and counseling: Do they help the bereaved?. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.01.004

11 Harris (2011)

12 Bruce, E. J., & Schultz, C. L. (2001). Nonfinite Loss and Grief: a psychoeducational approach. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL8601025M/Nonfinite_Loss_and_Grief

13 Ibid.

14 Cianfrini, L. R., Richardson, E. J., & Doleys, D. (2021). Pain psychology for clinicians: A Practical Guide for the Non-Psychologist Managing Patients with Chronic Pain. Oxford University Press.

15 Ibid.

16 Wetherell, J. L. (2012). Complicated grief therapy as a new treatment approach. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.31887/dcns.2012.14.2/jwetherell

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Iglewicz, A., Shear, M. K., Reynolds, C. F., Simon, N. M., Lebowitz, B. D., & Zisook, S. (2019). Complicated grief therapy for clinicians: An evidence‐based protocol for mental health practice. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22965

20 Speedlin, S., Milligan, K., Haberstroh, S., & Duffey, T. (2016). Using acceptance and commitment therapy to negotiate losses and life transitions. Research Gate.

21 Bohlmeijer, E. T., Fledderus, M., Rokx, T., & Pieterse, M. E. (2011). Efficacy of an early intervention based on acceptance and commitment therapy for adults with depressive symptomatology: Evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.10.003

22 Malmir, T., Jafari, H., Ramezanalzadeh, Z., & Heydari, J. (2017). Determining the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) on life expectancy and anxiety among bereaved patients. https://doi.org/10.5455/msm.2017.29.242-246

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.