Introduction

Since January 20, 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has proved to be a crisis that will impact the world for years to come. Although the pandemic has consistently been presented as a physical health crisis, its prolonged and uncertain effects have negatively impacted mental health, especially for vulnerable populations. This increased mental distress during the pandemic is occurring against already existing high rates of mental illness and substance use in the United States. The pandemic has led to isolation and occupational/academic shifts, which have already been established as stressors that make people especially vulnerable to mental health problems. The pandemic’s safety precautions (e.g., such as social distancing) have also imposed additional barriers in the help-seeking process for all individuals, both those who have just started to experience negative mental health and those whose mental health has gotten significantly worse.

Systematic reviews have found an association between the pandemic and greater anxiety and depression in the general population, with more pronounced effects among specific demographic and minority groups. From April to June 2020, during one of the first peaks of the coronavirus pandemic, anxiety disorder and depressive disorder symptoms increased significantly in the United States when compared with the same months in 2019.[1,2]

Anxiety during a pandemic is not surprising. The unpredictability of the coronavirus, paired with the fear of becoming infected with an unknown virus, elicits anxious symptoms. Continual news reports of increasing death tolls and infection rates further increase this anxiety. COVID-19 symptoms and anxiety symptoms overlap, with many similarities, and also impact each other, making the other worse. For instance, anxiety’s somatic symptoms, such as sweat and muscle pain, could be confused with COVID-19 symptoms, heightening fear and worry in the individual.

There are increased mental health burdens associated with the pandemic; these burdens are disproportionately impacting groups that were already at heightened risk pre-pandemic, such as individuals with low socioeconomic status, racial/ethnic minorities, and sexual/gender minorities. One study comparing depressive symptom prevalence between pre- and post-pandemic times found that prevalence increased by three-fold throughout the pandemic, with greater risk observed among individuals with lower income and a greater number of pre-pandemic stressors.[3] A 2021 CDC report announced that the “percentage of adults with recent symptoms of an anxiety or depressive disorder increased significantly from 36.4% to 41.5%.”[4] This increase was most prominent for two groups of people: adults aged 18 to 29 years old and those with less than a high school education.[5]

Conversely, other studies indicate that Americans have shown resilience. A self-report study on 157,213 Americans found that anxiety increased initially in the first few months of the pandemic, but later returned to baseline.[6] However, sadness and depression continued to increase in later pandemic months, probably as residual effects of the increased uncertainty and worry in the early months of the outbreak. Despite these initial and persisting negative impacts, the present study, conducted by Yarrington et al., suggests that many Americans demonstrated resilience over the span of the pandemic in the United States.[7]

Economic downturn: unemployment & income inequality

The COVID-19 pandemic was responsible for one of the worst economic recessions the United States had seen in years. These rapid changes to our economy created additional stressors, further striking the mental health of certain individuals. For instance, a review conducted under the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) compiled that adults experiencing unemployment reported higher rates of anxiety and depressive disorder compared to adults who didn’t experience job loss. The figure below shows this drastic difference in rates, with 53.4% of respondents who lost their jobs reporting symptoms, while only 32% of individuals who didn’t lose their jobs reporting the same symptoms.[8]

Anxiety and depression increases were not the only mental health consequences linked to the pandemic. Other outcomes included substance use disorder and suicidality. Previous research from earlier economic downturns has consistently found that job loss is associated with increased depression, anxiety, distress, and low self-esteem, all of which lead to a higher risk for substance use disorder and suicidality. For example, the 2008 to 2010 economic crisis was correlated with an additional 10,000 suicides in Europe and North America.[9] The same KFF review above found that when compared to households experiencing no income decreases or unemployment, households that did experience these disturbances reported higher rates of pandemic-related worry or stress, resulting in significant decreases in their mental health and well-being. Some of these developments included difficulty eating and sleeping, increases in alcohol abuse and substance use, and worsening pre-existing chronic conditions.[10]

A negative correlation has been found between annual income and the susceptibility of developing mental health disorders due to the pandemic. Households with lower incomes were more likely to report major negative mental health outcomes throughout the pandemic. One of the KFF tracking polls observed that 35% of those earning less than $40,000 reported experiencing at least one adverse mental health outcome, while only 21% of those who earned between $40,000 to $89,000 and 17% of those earning $90,000 or more reported the same.[11]

BIPOC community

Not only has the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacted the BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) community in terms of death and infection rates, but they have also been more likely to report a greater number of adverse mental health effects. Due to longstanding systemic and institutional inequities, BIPOC individuals are already at a heightened risk for a multitude of conditions that make them more vulnerable to poorer physical and mental health, such as low socioeconomic status, lack of access to healthcare and education, and greater job instability. For example, BIPOC individuals already constitute an overrepresentation in essential jobs (e.g., the transportation sector, where socially distancing is more difficult) they are therefore more susceptible to COVID-19 transmission and subsequent negative mental health effects.

Even before the pandemic, BIPOC groups were already at a magnified risk for mental health disorders due to the pronounced lack of access to mental health care services. Historically, these communities of color have faced marked challenges accessing mental health care. The scarcity of culturally-adapted evidence-based treatments, as well as low minority representation within the field, impose barriers to the therapeutic alliance, increasing the likelihood of People of Color avoiding and dropping out of therapy. The pandemic has only further increased this gap in mental health problems and access.

Below is a figure breaking down the mental health impact the pandemic has had on different racial/ethnic groups. As the figure demonstrates, non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics/Latinos are at the top of the breakdown, with 46% to 48% reporting anxious or depressive symptoms, a significantly higher proportion compared to the 40.9% share in the non-Hispanic White sample.[12]

Although African Americans make up only 13% of the United States population, they have comprised 30% of COVID-19 patients (whose race was known) and 34% of COVID-19 deaths in 29 states.[13] The CDC compared the risk for COVID-19 hospitalization and death between racial/ethnic minority groups and White individuals. They found that African Americans were 2.5 times more likely to be hospitalized and 1.7 times more likely to die.[14] Likewise, Latinos were 2.4 times and 1.9 times more likely, respectively.[15]

Moreover, the intersection of race and socioeconomic status magnifies these impediments. Most of the safety precautions that individuals could take during a pandemic, like hand-washing and social distancing, are “functions of privilege”.[16] Andoh (2020) notes that a likely factor contributing to the disproportionate rates of infection and deaths is that People of Color are more likely to live in racialized and impoverished neighborhoods, with limited or no access to sanitation and health care.[17]

Throughout the pandemic, Asian Americans have been the targets of raging xenophobia throughout the United States. Negative stereotypical language about the COVID-19 pandemic, such as “Chinese virus” and “Kung flu”, increased rates of anti-Asian discrimination in the United States. Racial trauma, which occurs as a result of microaggressions, discrimination, and racism, negatively impacts the mental health of targeted groups. These discriminatory and racist thoughts and acts have been found to contribute to poorer health and increased rates of chronic health illnesses.[18,19] A 2015 meta-analysis on racism and mental health found that racism was significantly correlated with poorer mental health, such as anxiety, depression, and psychological stress.[20]

Essential workers

Essential workers were and continue to be the backbone of the United States economy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, grocery, healthcare, package, and delivery employees are at a heightened risk of contracting COVID-19. Additionally, these workers are at a heightened risk of developing symptoms of depression and anxiety. Significantly more essential workers reported these symptoms than non-essential workers (42% to 30%).[21] In addition, 25% of essential workers reported starting or increasing substance abuse and 22% of them reported suicidal ideation, while only 11% and 8% of non-essential workers reported the same, respectively.[22] The figure below visually depicts these contrasts.

School-aged children & their parents

To prevent further COVID-19 spread, schools at all grade levels shut down at a nationwide level and transitioned to online learning in 2020. These school closures disrupted families’ routines and dynamics, especially through the sudden lack of childcare, as many working parents depend on schools as a form of daycare. Children were also deprived of a major source of human contact and knowledge, a developmental necessity. As developmental psychologists have argued, children need interactions with people outside of their immediate family network (e.g., teachers and peers) in order to develop accordingly and healthily. A 2018 comprehensive review on the role several macro- and micro-contexts have on child development, “Early care and education settings are, next to the family, the most important social contexts in which early development unfolds”.[23] Teachers can serve as protective factors, instilling motivation and providing psychological support.[24] In-person schools have the capacity to not only facilitate the attainment of concrete knowledge but also enhance social and emotional competencies.[25] The shift to remote learning for prolonged periods of time significantly impacted the well-being of school-aged children. A study with a representative sample of primary and secondary Chinese students found that the three most prevalent symptoms were anxiety (24.9%), depression (19.7%), and stress (15.2%).[26] A protective factor was parent-child discussion, characterized as the amount of pandemic-related discussion between the child and their parent(s).[27]

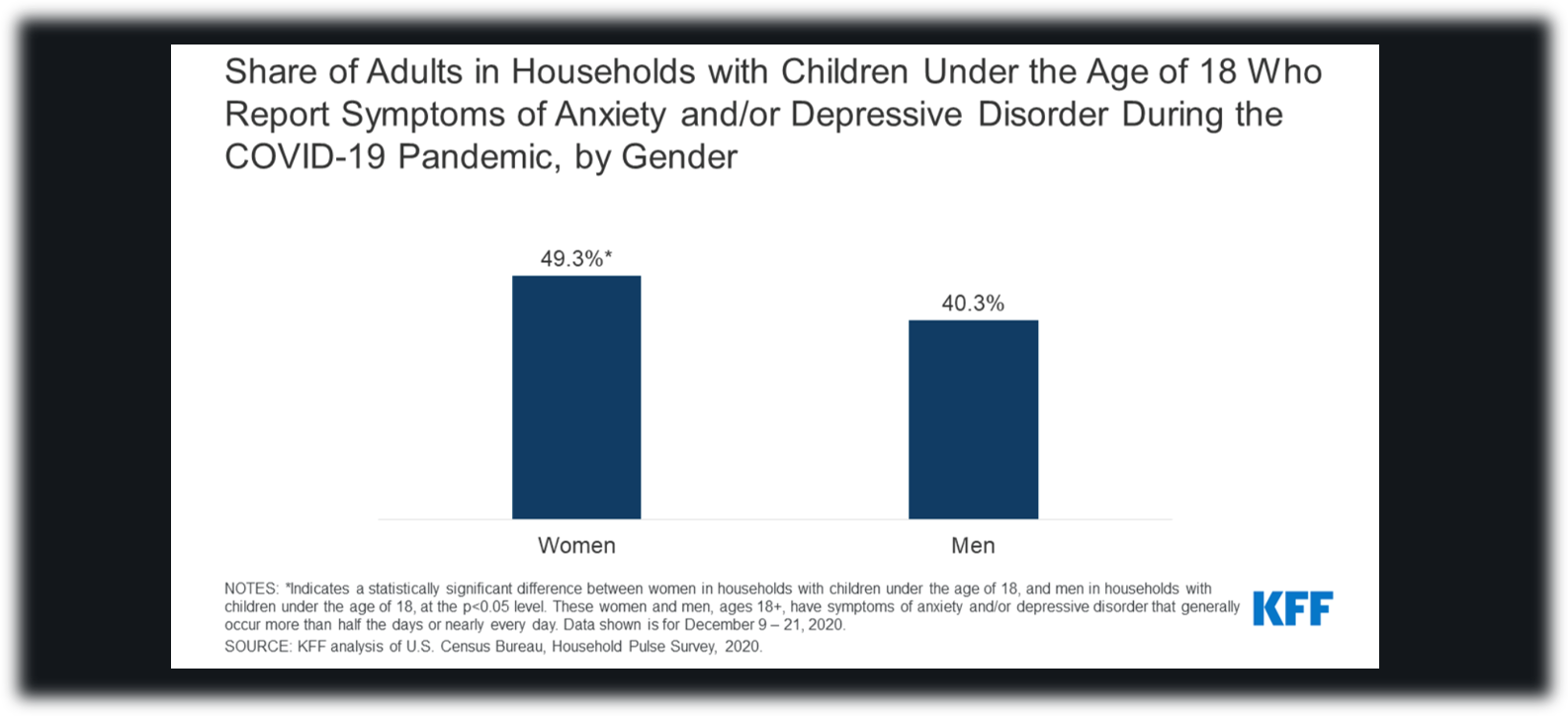

Not only are parents concerned about their childrens’ well-being, but parents are also at heightened risk of negative mental health outcomes. This effect was also found to occur differentially based on gender in heterosexual relationships, with mothers being more likely to report these outcomes than fathers. The figure below shows this differing impact.[28] Pre-pandemic, women were already more likely than men to report decreased mental health. The pandemic has only further escalated this gender difference.

The mental well-being of parents and children affected each other bidirectionally, with high paternal stress correlated with worsened mental health in children, and worsened mental health in children correlated with decreased parental well-being. A national survey on the well-being of parents and children throughout the COVID-19 pandemic found that higher rates of poor mental health for parents simultaneously occurred with deteriorating behavioral health for children in approximately 1 in 10 families.[29] Among these families, 48% reported loss of child care, 16% reported change in insurance status, and 11% reported worsening food security.[30]

Adolescents and young adults

Adolescence and young adulthood are critical developmental periods characterized by an increase in independence, often by starting college, moving out of one’s childhood home, exploring more serious romantic relationships, and entering the workforce. Yet, the pandemic and its accompanying restrictions have put a halt to these milestones. For young people, the disruptions to access to mental health services, school closures, and employment crises have most prominently impacted their well-being.

Though initially one of the most low-risk groups for COVID-19 infection and death at the start of the pandemic, adolescents and young adults could arguably be the demographic whose mental health has been most negatively impacted. This disproportionate effect can be traced to the pandemic’s role on diminished, and even nonexistent, social relationships and a weakened sense of belonging. Young adults, with all the changes they undergo during this developmental period, are a high-risk group for loneliness, to begin with. Fluctuating social networks and a greater sense of independence away from the family unit predispose this population to higher levels of loneliness. Add onto that the social distancing and lockdowns associated with the pandemic, and an already potentially lonely demographic is now even less connected to others. To make matters worse, although mental health illness increased among this demographic, support stayed stagnant.

According to a report sponsored by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, young people (15 to 24-year-olds) were 30% to 80% more likely to report symptoms of depression or anxiety than adults in Belgium, France, and the United States in March 2021; additionally, they also reported higher levels of loneliness.[31] Despite the slow return to “normal” and reopening of society, the prevalence of anxious and depressive symptoms among young people remains higher than pre-pandemic levels, demonstrating the pandemic’s significant leftover effects.

Among college students specifically, multiple studies have found that over 70% have reported increases in stress, anxiety, and depression. Most students attribute these increases to worries about the health of themselves and loved ones (91%), deficits in concentration (89%), sleep disruptions (86%), decreases in belongingness and social interactions (86%), and academic performance worries (82%).[32] College students have adopted a variety of coping mechanisms, both positive and negative. These include support from family and friends, exercise, meditation, and new hobbies, to increases in alcohol and drug consumption, and procrastination.[33]

Sexual and gender minorities

When compared to heterosexual and cisgender populations, sexual and gender minorities experience greater health disparities. These pre-existing mental health incongruities have made them particularly vulnerable during a time like the COVID-19 pandemic. According to a review by the American Psychological Association (APA), these groups reported notably higher rates of alcoholism, substance abuse, PTSD, depression, anxiety, OCD, and suicidal behaviors throughout the pandemic.[34]

Sexual and gender minorities experience paramount barriers to medical care, both physical and mental. The lack of culturally competent, respectful, and accepting healthcare providers elicits medical distrust and avoidance. Baumann et al. (2020) note that queer and trans individuals were already more likely to be homeless or lack access to resources pre-pandemic.[35] The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated these inequities. For queer youth, in particular, pandemic-related school closures may have severed access to potential support structures outside of the home, such as peers, school clubs/organizations, and school counselors. This community-building, a well-known resilience factor for sexual and gender minorities, was hindered by COVID’s social distancing and stay-at-home policies.

A KFF tracking poll attempting to examine the pandemic’s impact on LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) individuals found that almost three-fourths (74%) say worry and stress from the pandemic has harmed their mental health.[36] Conversely, only 49% of respondents who are not LGBT, reported the same.[37] Another study conducted by Moore et al. (2021) found that the LGBT population had significantly higher rates of pandemic-related depression and anxiety symptoms, often surpassing clinical concern thresholds.[38]

What the mental health field can do to mitigate these disproportionate outcomes

It is important to note that all the demographics listed above do not exist in isolation. Many individuals identify under multiple categories, such as African-American mothers, Asian American college students, or a low-income and transgender essential worker. When there are multiple avenues of oppression and disadvantage, all of the negative impacts listed above are intensified. To combat these intersectional inequities and aid marginalized communities, the APA recommends that psychologists “understand their place, be a partner (not a savior), encourage the use of bystander intervention, and be an advocate.”[39]

Psychologists must recognize their own biases and privilege. Exhibiting cultural competence and humility, and actively committing to anti-racist practices, are essential components for effectively addressing and treating the ill-proportioned mental health struggles of minority populations. The APA loosely defines cultural competence as, “the ability to understand, appreciate and interact with people from cultures or belief systems different from one's own.”[40] Before the lack of minority representation in the mental healthcare field can be tackled, which is due to a variety of deep-rooted issues, current providers should be equipped with cultural competence and anti-racist guidelines. Evidence-based treatments (EBTs), and the field of psychological science as a whole, has a long history of ignoring minority groups by only studying WEIRD samples (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic). Therefore, cultural adaptations to existing EBTs are crucial for equity in care. Meta-analyses conducted on the efficacy of these modified EBTs have concluded that they are widely effective for marginalized groups.[41]

Cultural humility is an added factor to cultural competence. It shifts this knowledge-based stance to a lifelong learning process. One must also account for within-cultural variation. For example, although Latinx is one categorical division, there are actually 33 countries throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, each with unique histories and traditions. Additionally, Latinx individuals born in the United States encounter very different life trajectories and events compared to their immigrant counterparts. Therefore, achieving a balance between gaining knowledge while also recognizing and prioritizing individual differences is crucial.

An example of these cultural considerations is the Cultural Formulation Interview, which is a semi-structured interview to elicit a client’s racial identification and cultural background. The salience of identities varies by client. Although a therapist can have two clients that identify as Latina women, one of them may prioritize their womanhood more, while the other may prioritize their latinidad (Latinx ethnicity) more. The questions within this interview guideline allow therapists to gauge the importance and hierarchies that clients have about their identities and culture. The mere process of asking these types of questions strengthens the therapeutic alliance because it demonstrates care to clients. Through this strengthening, one of the main barriers that minorities experience, lack of a connection with their therapist and subsequent dropout, is prevented. It is key to remember that there is no end goal when learning about the history and struggles of marginalized communities. Thus, providers must follow the client’s lead and view cultural competence as a continual learning process which will benefit society throughout the pandemic and beyond.

For more information, click here to access an interview with Psychiatrist David Neubauer on insomnia & anxiety.

Contributed by: Nicole Izquierdo

Editor: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D.

References

1 CDC, National Center for Health Statistics. Indicators of anxiety or depression based on reported frequency of symptoms during the last 7 days. Household Pulse Survey. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm

2 CDC, National Center for Health Statistics. Early release of selected mental health estimates based on data from the January–June 2019 National Health Interview Survey. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/ERmentalhealth-508.pdf

3 Ettman, C. K., Abdalla, S. M., Cohen, G. H., Sampson, L., Vivier, P. M., & Galea, S. (2020). Prevalence of Depression Symptoms in US Adults Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2019686–e2019686. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686

4 Vahratian A, Blumberg SJ, Terlizzi EP, Schiller JS. Symptoms of Anxiety or Depressive Disorder and Use of Mental Health Care Among Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, August 2020–February 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:490–494. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e2

5 Ibid.

6 Yarrington, J. S., Lasser, J., Garcia, D., Vargas, J. H., Couto, D. D., Marafon, T., Craske, M.

G., & Niles, A. N. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health among 157,213 Americans. Journal of affective disorders, 286, 64–70

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.056

7 Ibid.

8 Panchal, N., Kamal, R., Cox, C., & Garfield, R. (2021, February 10). The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use. KFF. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/

9 Reeves, A., McKee, M., & Stuckler, D. (2014). Economic suicides in the Great Recession in Europe and North America. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 205(3), 246–247. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.144766

10 Panchal, N., Kamal, R., Cox, C., & Garfield, R. (2021). KFF.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Andoh, E. (2020, May 1). How psychologists can combat the racial inequities of the COVID-19 crisis in American Psychological Association. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19/racial-inequities

14 CDC. (2022, February 1). Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death By Race/Ethnicity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

15 Ibid.

16 Andoh, E. (2020).

17 Ibid.

18 Williams, D.R., Lawrence, J.A., Davis, B.A. & Vu, C. (2019). Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Services Research, 54 (S2), 1374-1388. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13222

19 Williams, D.R. & Mohammed, S.A. (2013). Racism and health I: Pathways and scientific evidence. American Behavioral Scientist, 57, 1152-1173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213487340

20 Paradies, Y., Ben, J., Denson, N., Elias, A., Priest, N., Pieterse, A., Gupta, A., Kelaher, M., & Gee, G. (2015). Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE, 10(9), e0138511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511

21 Panchal, N., Kamal, R., Cox, C., & Garfield, R. (2021). KFF.

22 Ibid.

23 Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2020, January 24). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24:1, 6-36. 10.1080/10888691.2017.1398650

24 Ibid.

25 Flook, L. (2019). Four Ways Schools Can Support the Whole Child. Greater Good. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/four_ways_schools_can_support_the_whole_child

26 Tang, S., Xiang, M., Cheung, T., & Xiang, Y.-T. (2021). Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: The importance of parent-child discussion. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.016

27 Ibid.

28 Panchal, N., Kamal, R., Cox, C., & Garfield, R. (2021). KFF.

29 Patrick, S. W., Henkhaus, L. E., Zickafoose, J. S., Lovell, K., Halvorson, A., Loch, S., Letterie, M., & Davis, M. M. (2020). Well-being of Parents and Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey. Pediatrics, 146(4), e2020016824. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-016824

30 Ibid.

31 Takino, S., Hewlett, E., Nishina, Y., & Prinz C. (2021, May 12). Supporting young people’s mental health through the COVID-19 crisis. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=1094_1094452-vvnq8dqm9u&title=Supporting-young-people-s-mental-health-through-the-COVID-19-crisis

32 Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., & Sasangohar, F. (2020, March 9). Effects of COVID-19 on College Students’ Mental Health in the United States: Interview Survey Study J Med Internet Res 2020; 22(9): 21279. https://doi.org/10.2196/21279

33 Ibid.

34 Baumann, E., Kishore, A., Page, K., Ryu, D., Skinta, M., & Wagner, K. (2020, June 29). How COVID-19 impacts sexual and gender minorities in American Psychological Association. Retrieved February 25, 2022, from https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19/sexual-gender-minorities

35 Ibid.

36 Dawson, L., Kirzinger, A., & Kates, J. (2021, March 11). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on LGBT People. KFF. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-lgbt-people/

37 Ibid.

38 Moore, S. E., Wierenga, K. L., Prince, D. M., Gillani, B., & Mintz, L. J. (2021). Disproportionate Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Perceived Social Support, Mental Health and Somatic Symptoms in Sexual and Gender Minority Populations. Journal of Homosexuality, 68(4), 577–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2020.1868184

39 Andoh, E. (2020).

40 Deangelis, A. (2015, March). In search of cultural competence. American Psychological Association. Vol 46, No. 3. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.apa.org/monitor/2015/03/cultural-competence

41 Ibid.