Anxiety Snapshot

Approximately 25% of adults in the United States will experience an anxiety disorder in their lifetime.[1] Feelings of anxiety and worry can stem from regular daily events such as taking an important exam, giving a speech, or going on a first date. Normal occurrences as such will not always point to the presence of an anxiety disorder. However, when feelings of worry and negative thought patterns are chronic and uncontrollable, they can indicate that an anxiety disorder is present.[2] Experiences of anxiety can vary from person to person, and different types of anxiety disorders can provoke various uncomfortable feelings or thought patterns. BetterHelp (2022) lists the ten most common “hallmarks” of an anxiety disorder whether it be generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder or social anxiety disorder (i.e., social phobia):[3]

Excessive Worry - Experiencing a sense of dread that lasts six months or longer about regular topics such as school, work, social life, relationships, heath, and finances.

Difficulty Sleeping - Lying awake at night and not being able to fall asleep due to anxious or fearful thoughts about a possible upcoming event.

Fatigue - Feeling exhaustion throughout the day or becoming easily tired even if one gets an adequate amount of sleep.

Trouble Concentrating - Procrastinating either knowingly or unknowingly and struggling to complete daily tasks at school or work due to blanking out.

Irritability and Tension - Feeling on edge regularly or becoming easily angered when stressed out. Tension can also present itself physically in tense muscles or aches and pains.

Increased Heart Rate - Experiencing rapid heart rate or irregular palpitations can occur during panic attacks and episodes of social anxiety.

Sweating and Hot Flashes - Feeling one’s body temperature rise can stem from increased heart rate and higher blood pressure.

Trembling and Shaking - Feelings of fear and anxiety can induce limb shaking, especially in the hands. A state of heightened adrenaline and a fight-or-flight response can cause shaking as well.

Chest Pains and Shortness of Breath - Limiting the amount of oxygen in the lungs can cause chest pains, particularly during panic attacks. One may feel a sensation of tightness in the chest.

Feelings of Terror or Impending Doom - Feeling like something negative is going to occur can happen suddenly and come from an unknown source. Such feelings are likely to be disproportional to the actual events causing anxiety and panic.

Mindfulness Meditation as a Modern Practice

The field of positive psychological research has a common goal of focusing on what can go right in life, also known as positive affect. Positive affect can include enjoyment, personal connection, and states of pleasant feelings.[4] Deliberate trainings of positive emotions are referred to as Positive Psychology Interventions (PPIs); mindfulness meditation (MM) is one of the most effective known PPIs (Morgan, 2021). MM recently made its way into Western culture during the last century and can be defined as, “The awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment”.[5] As a result of practicing MM, emotions can be regulated, and physiological and mental changes can occur, enhancing one’s reality.[6]

Mindfulness meditation manifests in two forms: state mindfulness and trait mindfulness. State mindfulness is the feeling of being present in the moment after practicing MM, whereas trait mindfulness is a practice one carries throughout their life, regardless of knowing about mindfulness or not.[7] There are five approaches one can take when practicing MM:[8]

Body Scan: Focusing on one’s bodily sensations; typically starting at the top of the head down to the toes.

Focused Attention: Holding concentration on one object or a specific feeling.

Open Monitoring: Allowing your mind to wander and focusing on the sensations it naturally is pulled towards while remaining present.

Mindful Movement: Utilizing practices such as yoga and tai chi to focus on one’s bodily sensations.

Loving Kindness: Visualizing oneself and others while cultivating feelings of gratitude, forgiveness, and love. First turning inward to oneself and progressing outward toward a cherished friend, a neutral person, a difficult person, and eventually everyone elsewhere.

Loving-Kindness Meditation and Loving-Kindness Coloring

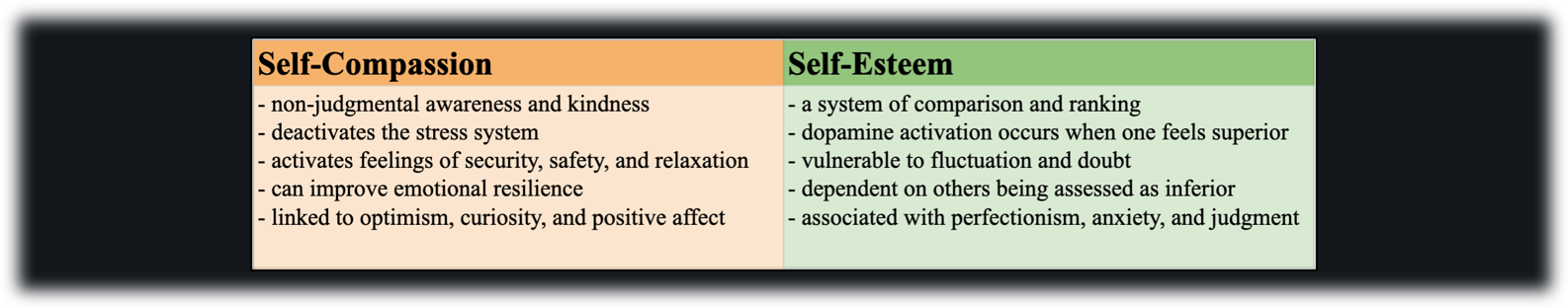

A study conducted in the United Kingdom by Mantzios et al. (2022) found that loving-kindness meditation (LKM) and loving-kindness coloring (LKC) were both successful in decreasing feelings of anxiety.[9] Previously mentioned in the last section, LKM is one of the primary and effective practices that show up in mindfulness meditation. LKC is an alternative practice where one redirects attention to a colorful design such as a mandala and actively observes one’s thought patterns to understand which thoughts are provoking certain feelings.[10] Ultimately, both LKM and LKC showed to partially increase state mindfulness, self-compassion, and decrease anxiety.[11] Having the choice between different meditation practices allows individuals to find what works best for them. Some limitations to the study include: the results were only minimally statistically significant and only included under-graduate students as participants. In the case of such limitations, future research should replicate the same study with more of a general population to improve the external validity of the information.[12]

Coping with Anxious Thought Patterns

Additional mindfulness approaches for coping with anxious and fearful thoughts include: thinking realistically, facing one’s fears, and getting regular exercise.[13]

Think Realistically

A real-life example of coping with anxiety using realistic thinking is when one is experiencing health anxiety. For instance, if an individual feels tired most of the time and wonders, “What if I have cancer and don’t know it?” Catastrophic patterns of thought can cause one to go down roads of fearful thinking that are counterproductive to becoming healthier.

First, one must identify the distorted thoughts that may be occurring on a regular basis. One way to identify a distorted thought is to change a “what-if?” question to an affirmative statement. For example, change “What if my low energy and fatigue are signs of cancer?” to “Because I have low energy and fatigue, I have cancer.” Then, question the validity of the affirmative statement. For instance, what are the actual odds that low energy and fatigue could be indicative of cancer and not something more simple and likely such as a lack of sleep, being overworked, overstressed or possibly dehydrated? Additionally, considering the results of an unrealistic outcome can bring about feelings of peace: “If the worst did happen, is it really true that I’d not find any way to cope?” Once you have assessed the validity of the statements, replace them with more realistic ones. Since there are several possible explanations for fatigue, the “worst-case” odds of having cancer in this scenario are very low.[14]

Face Your Fears

One of the most effective approaches to overcoming one’s fears is to face them head-on.[15] For individuals that experience phobia-related anxiety, facing fears can seem extremely off-putting. However, exposure should be a gradual, step-by-step process instead of immediate and sudden immersion into a fearful situation. This process, known as exposure therapy, usually involves a comprehensive plan to face one’s phobias when feasible.[16] Phobias are likely to induce avoidance behaviors, which can interfere with normal routines such as work or relationships and cause significant distress. Common phobias include: public speaking, riding in elevators, fear of flying, and fear of heights.[17] Sensitization (i.e., the process in which one becomes overly sensitive to particular stimulus) is a prime factor in the development of phobias. For example, a phobia of giving speeches in public can stem from past negative experiences with public speaking. These prior negative experiences are likely to lead to feelings of physical anxiety (e.g., sweating and shaking) as well as psychological symptoms (e.g., worry and low self-esteem). Real-life exposure allows one to unlearn the connection formed between a situation and an anxious response by re-associating feelings of calmness and confidence with that certain situation.[18] A licensed mental health professional can help direct one how to safely be exposed to stimuli they are afraid of.

Exercise Your Fears Away

Bourne and Garano (2016) note that getting regular exercise is one of the most powerful and effective methods to combat feelings of anxiety. The body’s natural fight-or-flight response is activated when faced with a perceived threat bringing along an influx of adrenaline. Exercise acts as a natural outlet for an overwhelming amount of adrenaline, diminishing the tendency to react with an anxious response to one’s fears.[19] Regular exercise has a direct effect on the following various physiological factors associated with anxiety:[20]

Reduction of Muscle Tension

Rapid Metabolism

Discharge of Frustration

Enhanced Oxygen of the Blood and Brain

Increased Levels of Serotonin

In addition to physiological factors, there are also several psychological benefits that accompany increased amounts of regular exercise:[21]

Increased Self-Esteem

Reduced Insomnia

Reduced Dependence on Alcohol and Drugs

Improved Concentration and Memory

Greater Sense of Control Over Anxiety

If feelings of anxiety are chronic and impact one’s everyday life, steps should be taken to reduce such negative experiences by contacting a licensed mental health professional for further guidance.[22]

Contributed by: Tori Steffen

Editor: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D.

REFERENCES

1 Bourne, E. J, & Garano, L. (2016). Coping with Anxiety: Ten Simple Ways to Relieve Anxiety, Fear, and Worry. New Harbinger Publications. https://ezproxy.snhu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1197205&site=eds-live&scope=site

2 BetterHelp. (n.d.) How to tell if you have anxiety: 10 signs and symptoms. (accessed 10-20-2022) https://www.betterhelp.com/advice/anxiety/how-to-tell-if-you-have-anxiety-10-signs-and-symptoms/

3 BetterHelp

4 Morgan, W. J., & Katz, J. (2021). Mindfulness meditation and foreign language classroom anxiety: Findings from a randomized control trial. Foreign Language Annals, 54(2), 389–409. https://doi-org.ezproxy.snhu.edu/10.1111/flan.12525

5 Kabat‐Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness‐based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156.

6 Morgan (2021)

7 Ibid.

8 Roeser, R. W. (2016). Mindfulness in students' motivation and learning in school. In K. Wentzel & D. Miele (Eds.), Handbook of motivation in school (pp. 385–487). Taylor and Francis. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301813078_Mindfulness_in_students'_motivation_and_learning_in_school

9 Mantzios, M., Tariq, A., Altaf, M., & Giannou, K. (2022). Loving-kindness colouring and loving-kindness meditation: Exploring the effectiveness of non-meditative and meditative practices on state mindfulness and anxiety. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 17(3), 305–312. https://doi-org.ezproxy.snhu.edu/10.1080/15401383.2021.1884159

10 Mantzios et al. (2022)

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Bourne & Garano (2016)

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Mantzios et al. (2022)