Understanding Self-Compassion

Research has found that increased self-compassion is linked to increased feelings of social connectedness, as well as decreased feelings of self-criticism, depression, rumination, thought suppression, and anxiety.[1] Those who are self-compassionate tend to possess psychological strengths such as happiness, optimism, wisdom, curiosity, initiative, and positive affect.[2] Additionally, self-compassion can improve emotional resilience when facing challenges or personal flaws, such as failing a test or social situation.

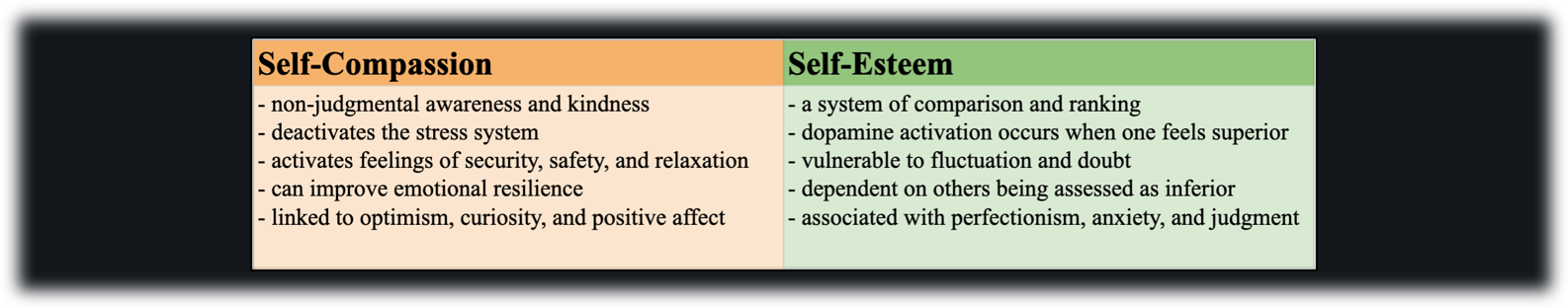

Self-compassion is not “positive thinking,” but rather the ability “to hold difficult negative emotions in non-judgmental awareness without having to suppress or deny negative aspects of one’s experience”.[3] This type of non-judgmental awareness has a multitude of potential applications, and studies have found that self-compassion can reduce harmful effects of disordered eating, improve interpersonal relationships, and promote healing in clinical settings.[4,5] In an interview with Dr. Mark Leary, a professor emeritus of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University, he notes that self-compassion is not only the effort of “reducing meanness toward oneself,” but also involves “the addition of kindness.”[6] Self-compassion also must not be confused with self-esteem, which instead of kindness, is a system of hierarchical ranking in which one derives pride from a sense of superiority.

While the benefits of self-compassion correlate with those of self-esteem, the two are distinct, as self-esteem rests on external evaluations and outcomes. Self-esteem is vulnerable to fluctuations and can be associated with perfectionism, anxiety, and self-judgment, since the elevated esteem toward oneself is conditional upon success. Research by Gilbert and Irons (2005) explores the divergence of these two qualities, finding that self-compassion deactivates the threat system and activates feelings of security, safety, and relaxation, whereas self-esteem alerts and energizes the body through dopamine when one perceives the self to be “better” in some way than others.[7]

Certain myths hold people back from letting go of judgmental self-talk and embracing a stance of warmth and understanding. Some don’t believe they are worthy of gentle affection, while others are afraid to let go of self-criticism out of fear that all their motivation for success will disappear along with it. Self-criticism is a habit that people can come to depend on as a galvanizer for change and progress. In conversation with Leary he explains how negative self-assessment is absolutely important and necessary for accurate and honest self-awareness and reflection. However, the reality that people occasionally fall short of their goals is not mutually exclusive with self-compassion. One can acknowledge failure while making sure not to add unnecessary cruelty and subjective, global judgments of themselves. Furthermore, research conducted by Leary et al., (2007) suggests that “highly self-compassionate [people] have more accurate perceptions of themselves than less self-compassionate participants.”[8] Maintaining a factual account of one’s shortcomings helps prevent self-talk that may be based in extrapolative, subjective, and global judgments such as “I am a failure.” By abstaining from derision and overwhelming self-criticism, the self remains in a state of safety, which is essential for growth to occur.

Learning to incorporate self-compassion into one’s life is no small feat. As Sonya Jendoubi, a therapist at Seattle Anxiety Specialists believes, “it’s a continuous process that involves commitment to the self through a willingness to face, explore, and understand the current way in which one relates to oneself.” Jendoubi finds self-compassion integral to her work with clients, and unremittingly relevant to the work that occurs in therapy. If one notices a dearth of self-compassion and wishes to change this, beginning therapy might be the next step. One can also begin to implement the components on their own. Kristin Neff, a pioneer in the field of self-compassion, has proposed three main components to achieving well-being via self-compassion: 1) self-kindness, 2) a sense of common humanity, and 3) mindfulness.[9]

Self-kindness - Flaws are noticed and treated gently, and the overall emotional tone when talking to the self is soft and supportive, like one would use to talk to a small child. When life proves challenging and painful, self-kindness looks like taking the time to turn inward and offer oneself soothing and comfort.

Common humanity - A shared sense of humanity involves recognizing that all humans are imperfect, fail, make mistakes, and engage in unhealthy behaviors. Life’s difficulties are framed in the light of commonality, inclusivity, and universality, such that one feels connected to others through their personal pain. When considering one’s flaws it is important to not cut oneself off from others, in the misbelief that one has failed unforgivably. Shaming oneself is the antithesis of self-compassion.

Mindfulness - Mindfulness includes awareness of the present moment in a clear manner. The first step to mindful self-compassion is recognizing the fact that one is suffering. Pausing to acknowledge one’s pain may seem rudimentary and overly-simple, but it can also be an immense challenge; it is crucial to pull oneself away from their current process of self-judgment or rumination to validate one’s own suffering. Neither ignoring nor ruminating is mindful.

Examples of what self-compassion can sound like:

“My date told me she ‘just wasn’t feeling it,’ and left early. I’m sad and feel insecure about a joke I said. Even though she didn’t particularly like me, I’m not defined by her opinion of me. Plenty of people appreciate my humor and find me attractive, and no one is liked by everyone. I will just let myself feel this sadness tonight though, because it always hurts to experience a form of rejection.”

“The job I wanted turned me down. This is extremely disappointing and I’m scared that no one will ever hire me. I have to remember that timing and other random external circumstances are always at play, and that I just wasn’t the best fit. Thinking about remaining unemployed is making my stomach and jaw tense. I am sending awareness to these areas in my body and taking a few deep breaths. This is not personal and I am still a hard-working, disciplined, and focused individual with lots of potential. Everything will be ok.”

“Everybody is awkward at one time or another. Just because I froze during that meeting and didn’t know what to say does not mean that I am exceptionally awkward or socially inept. I felt some shame and embarrassment afterward, but that is completely normal. I may have even reassured someone else who froze up during their last meeting that it is not the end of the world to not know what to say all the time.”

The biggest barrier to implementing more self-compassion into one’s life may be the challenge of just remembering to spend time focusing on self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness. Therefore, setting aside a few minutes each day or week to journal self-compassionately may jumpstart the routine of this mental response, moving oneself and closer to automatic self-compassion. For specific journaling prompts and other exercises targeting self-compassion, Neff provides several of these on her website.

As with all things healing, lasting, and good, this process of reworking your internal self-talk will take time. One should expect countless moments of recognizing the need for self-compassion only after the fact. Additionally, there will always be a part of the self that offers some criticism or judgment, so it’s important not to become defeated when perfection isn’t attained. And, one should remember to celebrate the moments in which they can smile at themselves, where they previously might have criticized.

Contributed by: Maya Hsu

Editor: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D.

References

1 Neff, K. D. (2009). Self-Compassion. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior (pp. 561-573). New York: Guilford Press.

2 Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K. L., & Rude, S. S. (2007). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004

3 Neff, K.D. (2009).

4 Adams, C. E., & Leary, M. R. (2007). Promoting self–compassionate attitudes toward eating among restrictive and Guilty Eaters. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(10), 1120–1144. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2007.26.10.1120

5 Williamson, J.R. (2014), Addressing Self-Reported Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in College Students via Web-Based Self-Compassionate Journaling

6 Leary, M., & Hsu, M. (2021, October 4). Psychologist Mark Leary on Self-Compassion. Seattle Psychiatrist Magazine. Retrieved October 5, 2021, from https://seattleanxiety.com/psychology-psychiatry-interview-series/2021/10/4/psychologist-mark-leary-on-self-compassion

7 Gilbert, P. & Irons, C. (2005). Therapies for shame and self-attacking, using cognitive, behavioural, emotional imagery and compassionate mind training. In P Gilbert (Ed.) Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 263 – 325). London: Routledge.

8 Leary, M. R. et al., (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 887–904. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.887

9 Neff, K.D. (2009).