A Path to Healing

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health condition triggered by experiencing or witnessing a terrifying event. Currently experienced by approximately 3.5% of the U.S. adult population; it is estimated that 1-in-11 people will be diagnosed with PTSD in their lifetime.[1]

The most common types of events leading to the development of PTSD include:[2]

Combat exposure

Childhood physical abuse

Sexual violence

Physical assault

Being threatened with a weapon

A serious accident (e.g., vehicle crash)

Many other traumatic events also can lead to PTSD; these include: the sudden, unexpected loss of a loved one,[3] life-threatening medical diagnosis, natural disaster, fire, mugging, robbery, plane crash, torture, kidnapping, terrorist attack, mass shooting and other extreme or life-threatening events.[4]

Symptoms may include flashbacks, nightmares and severe anxiety, as well as uncontrollable thoughts about the event.[5] Most people who go through traumatic events may have temporary difficulty adjusting and coping, but with time and proper self-care, recovery can occur. If symptoms worsen, last for months or years, and interfere with your day-to-day functioning, you may have PTSD.

While trauma-focused psychotherapies are the most highly-recommended type of treatment for PTSD and provide the greatest evidence for recovery, you may wish to include some supportive self-care strategies. These include:

Journaling

Writing (including expressive, transactional, poetic, affirmative, legacy, and mindful writing) can increase resilience, and decrease depressive symptoms, perceived stress, and rumination.[6] Specifically, when people write and translate their emotional experiences into words, they may be changing the way their experiences are organized in the brain, resulting in more positive outcomes.[7] Guided, detailed writing can help people process what they’ve been through and help envision a path forward. Additionally, it can lower blood pressure, strengthen immune systems, and increase one’s general well-being. Resulting in a reduction in stress, anxiety, and depression, expressive writing can additionally improve the quality of sleep, leading to better focus, clarity and performance.[8]

Research has found that the most healing of writing must contain concrete, authentic, explicit detail. Linking feelings to events, such writing allows a person to tell a complete, complex, coherent story, with a beginning, middle, and end. In this retelling, the writer is transformed from a victim into something more powerful: a narrator with the power to observe. In the written expression of what occurred, people can reclaim some measure of agency and control over what happened.[9]

The following tips may help getting started with journaling:[10]

Make it a habit – try to stick to a routine.

Keep it simple – journal only for a few minutes; consider setting a timer.

Do what feels right – find what’s best for you and go with it.

Write about anything, with any type of pen/pencil, in any type of book – there are no rules, this journal is yours.

Get creative – write lists, make poetry, draft a letter to someone, doodle or draw art.

Aim small, win big – keep in mind that journaling isn’t a “magic fix”, but it will help and provide benefit, and will give back the effort you put in.

Grounding and 4-7-8 Breathing Techniques

Grounding strategies can help a person who is dissociating or overwhelmed by memories or strong emotions and help them become aware of the “here and now”. Examples of grounding techniques include:[11]

Stating what you observe around you (e.g., what time is it, what pictures are on the wall, how many books are on the table, etc.)

Decreasing the intensity of affect - clenching fists can move the energy of an emotion into fists, which can then be released; visualize a safe place; remember how you survived and what strengths you possess that helped you to survive the trauma.

Distract from unbearable emotional states - focus on the external environment (e.g., name red objects in the room or count objects nearby). Somatosensory techniques (e.g., toe-wiggling, touching a chair) can remind people of their current reality.

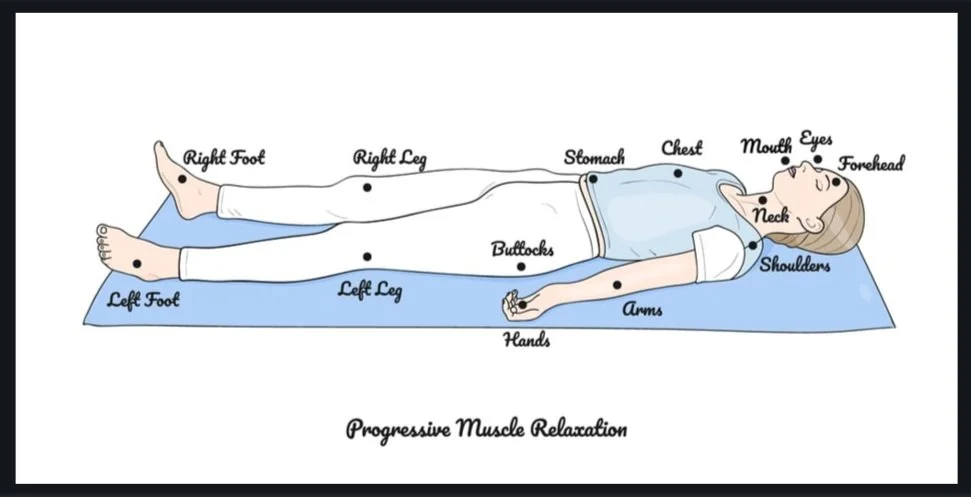

4-7-8 breathing techniques - controlled breathing is one way to move our systems out of a state of panic. Inhaling activates the sympathetic nervous system (fight-or-flight), while exhaling activates the parasympathetic nervous system (rest and digest).[12] To employ the 4-7-8 breathing relaxing technique:

breathe in for 4 counts

hold the breath for 7 counts

exhale for 8 counts

Note that any variation on these numbers should still elicit a calming response as long as the exhale is noticeably longer than the inhale.

Peer Support Groups

Within a peer support group, a person can discuss day-to-day problems with other people who have also been through trauma. While support groups have not been shown to directly reduce PTSD symptoms, they can help you feel better by giving a sense of connection to other people with similar, shared experiences. Further, peer support groups can help people cope with memories of a trauma or other parts of their life they are having difficulty dealing with as a result of the event. Dealing with and processing emotions such as anger, shame, guilt, and fear becomes easier when talking with others who understand.[13]

Similarly, group therapy may be another outlet one can employ to receive support as they recover from trauma.

Meditation & Mindfulness

Meditation practices can combat symptoms of PTSD as they have elements of exposure, cognitive change, attentional control, self-management, relaxation, and acceptance.[14] Specifically, mindful meditation orients one’s attention to the present with curiosity, openness, and acceptance. Experiencing the present moment non-judgmentally and openly may lead to the approach of (and not avoidance of) distressing thoughts and feelings, thus potentially leading to the reduction of one’s cognitive distortions.[15]

Healthy Diet & Exercise

A healthy neuro-nutritional diet is beneficial for both your mind and body. Good neuro-nutrition, based on a holistic and healthy diet of fresh fruits and vegetables, lean proteins, whole grains, nuts and seeds and spices and herbs, can improve moods and cognitive function, help reduce the risks of cognitive decline due to ageing as well as provide healthy nutrients to the rest of your body. Further, healthy neuro-nutrition can help improve the brain’s neuroplasticity (i.e., its ability to change) as well as neurogenesis (i.e., its ability to create new neurons.) Additionally, healthy neuro-nutrition helps to mitigate inflammation, which has been linked to a myriad of health deficits. Animal meats, hydrogenated oils, and many of the chemical and preservatives in processed foods have inflammatory qualities.[16] A healthy diet can also help address physical health conditions associated with PTSD, including diabetes, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome.[17]

Glucose is a critical nutrient to fuel a healthy mind and brain, with the healthiest sources of glucose found in unprocessed plant-based complex carbohydrates. By incorporating a steady, balanced supply of these vegetables, fruit, beans, nuts, seeds and whole-grain products, one can additionally achieve better mood regulation. The PTSD Association of Canada notes: blood sugar is balanced by having meals spaced fairly evenly, and eating every three to four hours. Choosing unrefined carbs and balancing those meals with protein and fat help delay the absorption of the glucose into the bloodstream. This can help keep your blood sugar level even, for both mood stability and appetite control.[18]

Exercise and other physical activity has been found to lessen the symptoms associated with PTSD. A 2022 meta-analysis by McKeon et. al., found that physical activity and structured exercise are inversely associated with PTSD and its symptoms. Moreover, exercise interventions may lead to a reduction in symptoms among individuals with, or at risk of PTSD.[19] Additionally, a 2021 meta-analysis by McGranahan and O'Connor notes that exercise training has promise for improving overall sleep quality, anxiety, and depression symptoms among those with PTSD.[20] The duration of exercise does not need to be significant in order to be effective. In fact, Pontifex et al., (2021) report that just twenty minutes of moderate intensity aerobic exercise has been shown to improve inhibitory control, attention and action monitoring.[21] To get the most out of one’s exercise, physical activity enjoyed outdoors has been shown to boost these beneficial effects.

It is important to keep in mind that the benefits of the afore-mentioned self-care tips will likely develop over time, following a consistent approach. Try not to get discouraged in the process and remember that some self-care tips will be more effective than others. Everyone’s path to recovery and healing will be different.

To learn more about PTSD, click here to access our interviews with experts on the subject; click here to access a multitude of articles including additional ways to recovery.

Contributed by: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D.

Editor: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D.

REFERENCES

1 “What is Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)?” American Psychiatric Association (accessed 7-5-22) psychiatry.org/patients-families/ptsd/what-is-ptsd

2 Ibid.

3 “Post-traumatic Stress Disorder,” National Institute of Mental Health (accessed 6-22-20) www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/index.shtml

4 “Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD),” Mayo Clinic (accessed 6-22-20) www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/post-traumatic-stress-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20355967

5 Ibid.

6 Glass, O., Dreusicke, M., Evans, J., Bechard, E., & Wolever, R. Q. (2019). Expressive writing to improve resilience to trauma: A clinical feasibility trial. Complementary therapies in clinical practice, 34, 240–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.12.005

7 “Writing Can Help Us Heal from Trauma,” Harvard Business Review (accessed 7-6-22) hbr.org/2021/07/writing-can-help-us-heal-from-trauma

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 “The Benefits of Journaling for Mental Health,” Diversified Rehabilitation Group (accessed 7-6-22) ptsdrecovery.ca/the-benefits-of-journaling-for-mental-health/

11 Melnick SM, Bassuk EL. Identifying and responding to violence among poor and homeless women. Nashville, TN: National Healthcare for the Homeless Council; 2000.

12 “Proper Breathing Brings Better Health,” Scientific American (accessed 2-16-22) www.scientificamerican.com/article/proper-breathing-brings-better-health/

13 “PTSD: Peer Support Groups,” U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (accessed 7-6-22) www.ptsd.va.gov/gethelp/peer_support.asp

14 Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:125–143. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg015.

15 Gallegos AM, Cross W, Pigeon WR. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for veterans exposed to military sexual trauma: Rationale and implementation considerations. Military Medicine. 2015;180:684–689.

16 “Neuro-Nutrition for a Healthier Brain,” PTSD Association of Canada (accessed 7-6-22) www.ptsdassociation.com/nutritional

17 McKeon, Grace; Steel, Zachary; Wells, Ruth; Fitzpatrick, Alice; Vancampfort, Davy; Rosenbaum, Simon. Exercise and PTSD Symptoms in Emergency Service and Frontline Medical Workers: A Systematic Review, Translational Journal of the ACSM: Winter 2022 - Volume 7 - Issue 1 - e000189 doi: 10.1249/TJX.0000000000000189

18 PTSD Association of Canada

19 McKeon, et. al.

20 McGranahan, M. J., & O’Connor, P. J. (2021). Exercise training effects on sleep quality and symptoms of anxiety and depression in post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 20, 100385. doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2021.100385

21 Pontifex, M. B., Parks, A. C., Delli Paoli, A. G., Schroder, H. S., & Moser, J. S. (2021). The effect of acute exercise for reducing cognitive alterations associated with individuals high in anxiety. International journal of psychophysiology : official journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology, 167, 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2021.06.008