An Interview with Sociologist Peter J. Stein

Dr. Peter J. Stein is a Professor Emeritus of Sociology at William Paterson University and a Holocaust scholar.

Jennifer Ghahari: Hey, thanks for joining us today. I'm Dr. Jennifer Ghahari, Research Director at Seattle Anxiety Specialists. I'd like to welcome with us Sociologist, Peter Stein. Dr. Stein has a Doctorate in Sociology from Princeton University, and has been a professor of sociology for 33 years, primarily at William Paterson University in New Jersey. Most recently he was a senior research scientist at UNC Chapel Hill. Since 2018 Dr. Stein has been volunteering, educating groups about the Holocaust at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Author of nine books, his most recent includes; “A Boy's Journey: From Nazi-Occupied Prague to Freedom in America.” Before we get started, can you please let our listeners know a little bit more about yourself and what made you interested in studying the Holocaust?

Peter Stein: Thank you for the introduction, Jennifer, and I'm glad to be here. I was born about two years before the Nazis and Hitler occupied, Czechoslovakia. I was born in Prague. First couple of years of my life were fine. But on June 15th, 1939, Germans came in, and the Holocaust started not much after that. My dad was Jewish, Viktor Stein, and he married a Catholic woman, my mother, Helen Zdenka Kvetonova. They had mutual interests. They liked music, they liked dancing. They fell in love, they married. And the fact that my Jewish father married a Christian woman, pretty much saved his life.

Jennifer Ghahari: Wow.

Peter Stein: Because unlike the other eight members of his family, his brothers and sisters and his mother, were all sent to concentration camps in 1942. My dad was not sent until two years later. He was doing slave labor. That is manual labor in and around Prague, which was difficult and demanding, but he survived. So, then he sent to Terezin in Czech or, quote, "Theresienstadt" in German, which was a ghetto-labor camp about an hour northwest of Prague. He was forced - he worked on wood manufacturing, is what he did before the war. That is, he had the Bentwood Manufacturing Factory. So, they made chairs. Anything with bentwood. Tennis rackets, skis, ping pong paddles, and so on...

So, he was able to apply some of those skills in Terezin. He came back in 1945. I remember him jumping off a Soviet truck. About 12 Russian soldiers brought back survivors of the Holocaust. He was still wearing a yellow star, which was required. So, then we went back to democracy, but the communist party came into power, and it took my parents almost two years to get an American visa. We came to the states the same night that Harry Truman upset Thomas Dewey for the presidency in 1948. Sailed by, The Statue of Liberty, her crown lit up, the torch lit up, and I saw downtown Manhattan. And I wanted to stay up all night. Why? Because I was looking for king Kong and Fay – climbing the edifice with Fay Wray. Finally, my mother said, no, go to bed. So, we came to the States. My father came two years later. It's a long story, but basically he was arrested by the communists for trying to get his factory back. My mom was a governess for a family with two children. And we lived with them in Larchmont, New York. I learned English. I went to City College. Then I went to Princeton for my PhD degree and I've taught in and around the New York area, primarily William Paterson. Jennifer's alma mater and where we also met and the rest is history.

Jennifer Ghahari: Great. Well thank you for sharing that with us and I'm sorry for everything that you and your family have been through, again, even begin to imagine. And again, thank you for speaking with us today. In terms of antisemitism that I think it's used fairly often. Can you explain to our listeners, what does that term actually mean?

Peter Stein: It's interesting. Historians and scholars still research and write about it. And most recently the current Biden administration appointed Deborah Lipstadt, who's a historian of the Holocaust, to a position overseeing Holocaust and genocide developments. So, it's come to that level of importance. And basically goes back to the Nazi ideology that Jews are inferior. They're inferior physically, they're inferior mentally and intellectually. And basically they have no right to survive. I mean, that's the essence of the Nazi ideology. That they're less than humans. And one film that the Nazi's produced shows Jews as vermin, as roaches to be destroyed...

And many people hope that the use of that term and attitude towards Jews would change with the end of World War II. However, all kinds of studies, one by ADL, the Anti-Defamation League shows an increase in antisemitism, both in the United States and in Europe. So, much so the latest study is a 2021 study. And I want to make sure that I report the figures correctly.

Jennifer Ghahari: Thank you.

Peter Stein: They do something where they count anti-Semitic incidents in the year 2021. They discovered 2,717 antisemitic incidents ranging from vandalism, putting a swastika or something of that sort, to violence in the synagogue and Pittsburgh, most notably the Tree of Life Synagogue and others. So, the antisemitism continues and I have to quote one noted authority. My mother. And when she was still alive, I asked her, well, why do you think there was so much antisemitism in Czechoslovakia?

She said envy. And I think there's something about envy. The Jews for millennia in Europe were segregated into ghettos, they were limited in what they can do. But in the 17th, 18th centuries in Europe, they were given more latitude, more opportunities. And they went into the professions, law, medicine, manufacturing, banking, and they were succeeding quite well. And I think the envy came in there because for generations, Jews were seen as inferior, less than human, to be avoided. And suddenly Jews had power and some had wealth. But I have to be very clear that yes, there were rich Jews and there were also very poor Jews. Many of them, the poorer ones in Eastern Europe, in agricultural areas. But that antisemitism had been spreading for generations before Hitler ever came on the scene.

Jennifer Ghahari: Wow. And as you said, it's spiking again. And it seems that hate groups are on the rise again. And aside from antisemitic attacks, there's also been a large increase in anti-Asian sentiments and attacks in the US. And it seems to correspond, especially with Asian Americans, with the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. And in America, we're talking about Jewish Americans and we're talking about Asian Americans. They're not outsiders, but some people are treating them as such. So, sociologically speaking, how can we overcome as a society, this discrimination against our own subgroups.

Peter Stein: I think you hit the nail on the head with the use of the word outsiders. I think one way to look at all of these issues is who's the insider, who's the outsider - who are the we, who are the they, who are the people with power and influence and who are those with limited? And I dare to say that in every society that we know of, there have been some people with more power and they can use the power to label other people as different that as outsiders. And among outsiders, if you look at it historically, were women, African Americans, Asians, Jews, people with disabilities, people with different sexual orientations. Any number of those people who then can be painted as dangerous, as different, as our kids shouldn't associate with them. And you quite right about Asians. It's been an ongoing struggle that we're now more aware of...

And Asian community are saying, we want protection. We want equal opportunities. We want equal rights. Chinese of course were built sent to your neck of the woods, the West Coast, to build railroads, primarily male workers, very few women. And so they were doing that kind of labor. The Japanese were the “good” group. They were the ideal group to the World War II when they were suspected of being pro German and sent to internment camps, which is a different word for concentration camps. And they suffered. And if you look at just one quick figure I was looking at, if you look at the proportion of Asians in technical jobs, chemistry, other sciences, is quite high. If you look at the proportion of CEOs in American corporations with Asian backgrounds it’s about 2%. So, they're promoted up to a certain point and then I think the stereotypes come in.

Jennifer Ghahari: Wow. Thank you. Sadly, and unfortunately, obviously it seems that you have firsthand experienced of the damage that extreme prejudice and discrimination can do. And are you comfortable to share some of your childhood experiences in Prague with our listeners?

Peter Stein: For those people looking for holiday gifts? There's a wonderful book - my memoir.

Jennifer Ghahari: It is a great book. I read it probably in two sittings.

Peter Stein: Wonderful. You didn't have some Czech wine with it, I hope. I hope it was Czech beer. It was difficult. My dad, would disappear for periods of time and I always would ask, this is during the war, during the Nazi occupation, during the Holocaust, I would ask my mother where's dad. And also where's my uncle Richard, my favorite uncle, brother of his, who would always bring me stuffed animals and toys. He was wonderful. My mom's standard answer was, “Your dad's on a business trip. He'll be back as soon as he can.” I checked with my cousin Gerti. Gerti also has a Catholic mother, Jewish father and her mother had the exact same answer that her sister did. That is, “Your dad is on a business trip. He'll be home as soon as possible.” So, I had no idea. I of course, had no sense of what Holocaust, what concentration camps were...

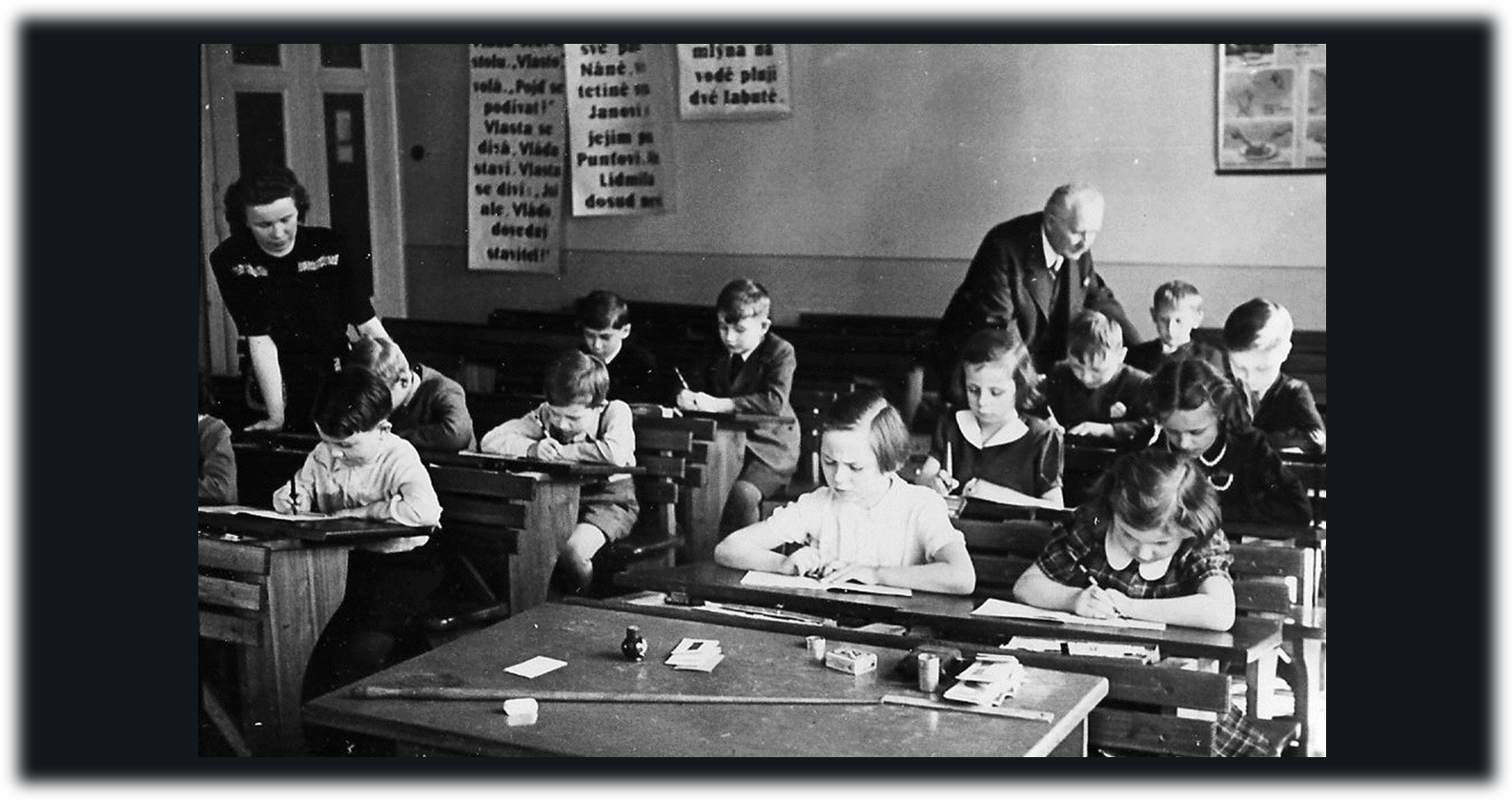

None of that. I went to school. But we had German soldiers all around. And in my classroom, every classroom in the front, there was a picture of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi flag. The teachers were Czech, but they were instructed to be quite reverential of Hitler and the Nazis. So, I'll give you one quick example of what I experienced as cognitive dissonance. Monday through Friday, we were told in class, when it came up that the Germans were winning. They even took us to a couple of parades to honor German soldiers coming back from the east. But on Sundays, I and my mother would visit my Catholic grandparents. And my grandmother was a wonderful cook, wonderful baker, always had a good meal, despite food shortages. She could put a chicken on the table at six o'clock like clockwork. Every Sunday when we were there, my grandfather invited me and my cousin, Robert, who was nine months older than I into a study. He would put on his Blaupunkt short wave radio and listen to the BBC, the British Broadcasting Corporation, which started with the chimes of Big Ben then Beethoven’s 5th (sings a few notes).

Jennifer Ghahari: That's very dramatic.

Peter Stein: And we'd have a bulletin of the news. And my grandfather spread a map of Europe on his desk. He had a stack of black checkers, which indicated the German positions and red checkers indicating the Allied positions, including D-Day in Normandy. And it was just amazing. And whenever we finished with him at his home, he would say, “Don't worry, your dad will come back.” He told both of us. Sadly, my dad did come back, he survived - my cousin's father, Leo Perutz was killed in Auschwitz. But that dissonance, what was happening: so, for a seven or eight year old, who do you listen to? Well, I went with my grandfather, but he said never about this in school...

If the teachers get a wind of it, you could get into trouble. So, the whole thing, the war years were difficult, including a couple of bombings of Prague. I have a whole chapter about that, where an American squadron flew over Prague, the same day they were supposed to bomb Dresden in Germany. They mistook the topography. It's very similar rivers. And so we lived through that. That was one of the scariest moments, because my school is in downtown Prague and they hit some buildings, the church, so on. So, the whole thing, the war was there, but somehow we managed and my mother was terrific. She looked after me, made sure we ate and all of that. And at the end of the war, she and I both became vegetarians. Why? We couldn't get any meat. So, I had fresh bread, which I loved with several different mustards. No meat. No hotdogs. Not a problem in Seattle these days.

Jennifer Ghahari: Exactly. You didn't stick with the vegetarianism. Did you?

Peter Stein: It ended as soon as the war ended. Butchers opened businesses, stores.

Jennifer Ghahari: Nice. Thank you for sharing that with us. It definitely helps to visualize what you and your family experienced. And now looking at what's going on in Ukraine, I think people might be able to see some connections. For those who aren't familiar on February 24th, Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered his army to invade Ukraine. And for those who have seen images on TV at home, the images and the stories are just gut wrenching and actually anxiety inducing. So, I can only imagine what you feel, seeing something like that. Cause it seems you some type of similar things that you went through back in Prague. From your own personal experience, can you speak of what you see going on in Ukraine? And are there any similarities?

Peter Stein: How many days do we have for this?

Jennifer Ghahari: Exactly.

Peter Stein: It's quite tragic, I must say. A couple of historical examples come to mind. In 1938, before Hitler invaded the whole country, he went to liberate an area called the Sudetenland. Sudetenland: about three million Czech citizens who spoke German as their native language. And Hitler used that pretext to liberate them from the Czechs, who he accused of oppressing. Putin’s take on it certainly is influenced by that kind of structuring. Then in 1948, the communists came into power in February and again in one day dictated censorship. So, my dad came home from his office in February midday, and he showed me the newspaper. He said, democracy has died in Czechoslovakia. I said, what do you mean? He shows me the newspaper and there're several columns, completely white. Those are stories that were never printed. Critical of, in this case, the communist takeover, what was called a putch.

And so Czechs had to flee. 20 years later, 1968, the Soviet army, well, the Warsaw Pact Nations in invade Czechoslovakia. People are probably familiar with that. And rest of my family, the Czech Jewish family that survived the war, left Prague one person at a time, because the rumor was that if you try to take your whole family out, you're likely to be questioned, even arrested. So, I spent a week in Vienna with my dad and every afternoon at three o'clock, we'd go to the railroad station to see if any relatives, and it literally took two weeks for the father, the mother, the daughter, and the son to come out. And you see it, people weren't being bombed, but they were limited to one suitcase.

And since I was there, I did a little study. I interviewed people for a couple of days. Most of them were in their thirties or forties, single or young parents, doctors, lawyers, nurses, social workers, teachers. What we would call a brain drain. And I think we haven't looked at the full impact in Ukraine of the Russian attack. How many other people have fled, had skills that are necessary. And it's very close to a genocide. Certainly they’re war crimes, the bombing of hospitals, of children's centers, of theaters, killing women and children, tying them up “in the name of freedom.” And it's hard not to think about domestic situation. I'm not going to go there, but the use of the concept of freedom and helping people themselves, you have to ask, who's doing the talking and what are the actions like? What's the behavior. It's not propaganda. It's what they do. And it's troubling. And now, as you know yesterday, the Secretary of Foreign Affairs for Russia, Mr. Lavrov, is talking about, they “have nuclear weapons,” while we know that, but that's...

Jennifer Ghahari: The similarities are highly disturbing, especially because it seems like you said that, it is ethnic cleansing, even though it's framed in the terms of liberation. But as you said, everything that they're doing is not liberation. It's the exact opposite.

Peter Stein: Brave Ukrainians. I don't know how many people would do that to risk their lives.

Jennifer Ghahari: Sure. And as you mentioned too, it's not only a brain drain. So, it's affecting Ukraine itself negatively because they're losing all of essential workers. And by essential, I also mean what you were saying, like doctors and people that keep society running. Like all of these people, it's millions have fled. But then also if you think of the flip side that now these people are refugees coming to different countries. I know out here in Seattle, we're supposed to get, I'm not sure how many refugees from Ukraine, but there's supposed to be several coming. And if they don't have a good handle on the English language, so you have someone like a doctor or professor or any profession, to get started over in a brand new country and to have lost so much. It's really heartbreaking. And I hope that when refugees go wherever they end up, whether it's here, whether it's the UK or anywhere, I hope people are cognizant of that. That these people are not here because they want to be. It's not that they left because they wanted to. Similar to you and your family. You left because you had to survive. And it wasn't an easy thing to do. Obviously you were a child when you came here and your English is perfect. But for older adults just getting a start, I can't imagine how difficult it is.

Peter Stein: Even my little example. (phone ringing) Sorry.

Jennifer Ghahari: No worries.

Peter Stein: I don't know how to quiet this.

Jennifer Ghahari: It wasn't me calling.

Peter Stein: Okay. My first few days in an American school with my lousy English, couple of kids thought I was German. Stein. I said, Stein, I'm Czech. I'm Jewish, I'm not German. And so imagine if you come... As you have said to be an immigrant, it's a difficult status. And is there anybody there? Fortunately had a wonderful teacher, Mrs. Murray in the seventh grade who took me under her wing and she helped me with English and writing and she was wonderful. And you think about the importance of teaching for immigrants English as a second language. My dad took one of those classes. He spoke Czech, he spoke German, he spoke French, but he didn't speak English.

Jennifer Ghahari: Wow.

Peter Stein: So, he had to come up to snuff and pass the citizenship exam. And you're so right, because it takes you out of your home. Out of settings of familiarity, to a brand-new country where they may or may not welcome you. And yet immigrants have done so much to build up this country. I mean the number of immigrants from Southeast Asia, from Asia. Seattle is certainly one place.

Jennifer Ghahari: And anxiety that comes from that type of move, especially when it's forced upon you. It's really detrimental. So, again, I hope that people are just a little bit more aware and a little bit more sensitive and will just kind of maybe take an extra step to try to help people however possible.

Peter Stein: And government policy is so critical. We won't speak about the former president who wanted to stop the incoming of any Muslims, of anybody. I mean, just willy-nilly. Well, so then it's not surprising that when they come, some Americans are upset. “You shouldn't be here, go back to where you came from.” And that kind of antisemitism and anti-minorities just makes being an immigrant that much more difficult. And I got to put a plug in for education because I think that's critical. That schools ought to welcome different points of view, different languages, different cultural patterns. And not start burning, taking books away. And no, you can't learn about this one or that one. That kind of blinders that some folks have.

Jennifer Ghahari: So, it sounds like multiculturalism and education are pretty much key to overcoming this anti-racism, antisemitism, basically all types of anti-discrimination. Correct?

Peter Stein: I would certainly hope so, because you may get it at home, but you may not. And so that's critical. Speaking one other point about antisemitism that the ADL League found, they're now looking at social media and the spread of antisemitism there. And they found that in one year in the United States, there were 4.2 million antisemitic tweets. And they go into their methodology, which is quite sophisticated, but 4.2 million antisemitic tweets.

Jennifer Ghahari: Wow.

Peter Stein: So, somebody's writing it, somebody's reading it, somebody's sending it out. And that's new. I don't think anyone else looks at the use of the media in that way.

Jennifer Ghahari: Right.

Peter Stein: Now one gentleman just bought a big media outfit and we'll see how goes.

Jennifer Ghahari: That should be interesting. Well, thank you. And so, as someone who specializes in antisemitism and wartime atrocities, do you have any other advice or any parting words for our listeners? Anything else that you want to add?

Peter Stein: Well, again to educate not only in schools, but educate yourself because the media, as, as lovely as it is, can be influenced. Who's saying it? Where does the message come from? Who's got what kind of vested interest in having you, accept this as a fact, as opposed to just an opinion. But also to communicate, to talk to other people, to talk against people who have racist jokes or sexist jokes, or rather than just ignore it and laugh, suggest how does this impact other people. Anti-gay or lesbian jokes, or what have you, and to support the right to vote. Another key issue that maybe needs more attention and the democracy supposedly is helping people, encouraging people to vote, to express their opinions. Well, if you make it more and more difficult, it's easier for people of one opinion to get in it and not others. So, I just would hope for more tolerance, more understanding of other people, as the salvation and the Golden Rule is to do unto others, as you would have them do unto you. And I think that's an important rule to keep in mind in our lives.

Jennifer Ghahari: Great. Well, thank you so much. And again, thank you for sharing with us, what you and your family had gone through. And I'm very sorry that you have experienced all of that. And if we could have you back sometime, we definitely will. Again, thank you for talking with us today.

Peter Stein: Thank you so much for inviting me. If anybody has any questions after they see the tape, feel free to communicate with me or through Jen. Glad to answer and thank you for what you are doing.

Jennifer Ghahari: Perfect. And you had mentioned that there may maybe some photos that we could add along with the interview.

Peter Stein: Sure.

Jennifer Ghahari: Perfect. So, for those listening we'll put that into the transcript section on our website and you'd be able to access that along with the link to Dr. Stein's book.

Peter Stein: Thank you.

Jennifer Ghahari: Thank you again.

Photo gallery images courtesy of Dr. Peter J. Stein:

Zdenka Kvetonova and Viktor Stein (Peter Stein’s parents), married in Prague’s Old Town Hall, May 1934.

Peter Stein and his Mother (left).

School children in Prague (2nd grade).

Photo taken during the May 5-8,1948 uprising by Czech partisans battling remaining German troops--eventually chasing them out of town.

1946 Prague: Peter Stein’s family along with Kurt Fuhr (Peter’s Father’s cousin) and his wife, Malvinka. Both Kurt and Malvinka were Jewish and Captains in the Czech Army, fighting with the Soviet Army against the German Army. They each received medals for bravery (he was wounded in battle and she was a nurse).

Arriving to the U.S. and seeing the Statue of Liberty for the first time.

Please note: The views expressed by the interviewee are for educational and informational purposes only, are not meant to diagnose or treat any condition, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Seattle Anxiety Specialists, PLLC.

Editor: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D.