Introduction

Historical Underpinnings

On paper, Asian Americans have the lowest official rates of mental illness, divorce, and juvenile delinquency out of any ethnic demographic in the U.S., as well as the lowest utilization of traditional mental health services.[1,2] At first glance, this might seem to demonstrate a true success story for Asian Americans: surveys of college students found a trend of beliefs that Asian Americans naturally have fewer mental health issues in comparison to their white counterparts.[3] However, this belief masks a sobering reality: female young adult Asian Americans in fact have the highest rate of suicide deaths of any racial and ethnic groups.[4] The façade of Asian American strength ignores many cultural factors hindering Asian Americans' disclosure and recognition of mental health conditions.

Cultural pressures against disclosure can be traced back to traditional norms within Asian motherlands as well as the pressures of coalescing into American culture and the subsequent model minority myth. Collectivist cultures within many Asian countries hold that mental health problems exist because of a lack of control, making it "shameful" to seek help through therapy rather than dealing in private.[5] In this sense, individuals' development of mental illness can be thought to result from a lack of proper guidance from their family members, reflecting badly on their familial honor and reputation.[6] Such pressures to restrain potentially disruptive and strong feelings can lead to low usage of support, withdrawal, denial, and even cutting off mentally ill family members.[7,8]

Crossing the ocean to America, historical discrimination and the accruement of generational traumas in Asian immigrants have also contributed to nondisclosure–particularly in relation to the model minority myth. Despite the common view of Asian Americans as an "immigration success story," that vision of success ignores a history of oppression. Collectively, since immigrating to America, Asians have been "the victims of laws that have denied them the rights of citizenship, ownership of land, and marriage and that have even forced the internment of over 110,000 Japanese Americans."[9] Perhaps ironically, the development of that success story was rooted in Asian Americans' oppression: in the nineteenth century, when the first wave of Chinese immigrants came to work on American railroads, they were compared to their Black counterparts and "praised for a superior work ethic."[10] During World War II and Japanese internment, Asian Americans felt pressures to act as "model citizens" in order to reduce racist sentiments, culminating in a 1966 New York Times article titled "Success Story, Japanese Style."[11] The article contrasted Asian Americans with "problem minority groups" to portray them as "rising above the barriers of prejudice and discrimination" and a "success story of meritocracy," as a means of dismissing civil rights activists' claims about racism.[12]

The Model Minority Myth: A Facade

Such an argument pastes a pretty façade over gaping problems. Asian Americans are not a monolith; the article's statements of a "higher median income" for Asian Americans ignores differences between higher income groups (for example, South and East Asians) and marginalized communities (for example, Southeast Asians) as well as the higher percentages of multiple wage earners in the family, equal incidence of poverty, and salaries not commensurate with educational levels of Asian American workers.[13,14] Besides heightening tensions with other minority groups, such a myth diverts attention from discrimination and prejudice against Asian Americans, and has even lowered research and policy interests in Asian American communities due to misconceptions that they do not require resources and support. The model minority myth ignores the historical xenophobia faced by Asian immigrants in America for centuries and now even today, with the current rise of anti-Asian hate during the COVID-19 pandemic.[15]

The creation of this façade can result in a form of gaslighting against Asian Americans experiencing mental health issues; the positive light can cause people to claim that no problems are happening, with the belief that Asian Americans are "immune from cultural conflict and discrimination."[16,17] Because of the prevailing belief that Asian Americans do not experience mental health conditions to the same extent as other demographics, American society can be dismissive of disclosed stresses and issues. Asian American parents can often portray a mindset that their child is making a big deal out of nothing and are in denial that their child needs mental health counseling, perhaps demonstrating an internalization of the model minority myth.[18]

The Pressure to Succeed

The parent-child relationship is in fact a key player in an Asian American child's experience with mental health, which is affected in large part by Asian cultural values and the model minority myth. Both influences place high expectations and high pressures on children to uphold familial honor and find a successful position in the "model minority" meritocracy. This pressure can adversely affect mental health: in a survey of Asian American children with mental health conditions, their largest reported source of stress was parental and societal pressures of high achievement.[19] The pressures exerted by the expectation of Asian success can compound with high parental expectations reinforcing the stereotype, making it difficult for children to reconcile these pressures and disregard the harmful stereotypes against Asian Americans.[20]

The high pressures of success placed on Asian American children–whether because of cultural tradition, parenting style, model minority myth, or a combination–are correlated with mental health difficulty. Asian American adolescents stereotyped as "academic overachievers" frequently experience serious mental health challenges, including higher social anxiety, lower self-esteem, and greater depressed mood and risk for self-injury.[21] Stemming from cultural values of familial honor and achievement as well as pressures of upward mobility in America, 28% of Asian American mothers and 19% of Asian American fathers can be described as a "tiger parent," whose harsh parenting styles coexist with warmth and attentiveness.[22] Although dependent on whether the child perceives this parenting as controlling or harsh, such disempowering parenting methods can be associated with anxiety, stress, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation in Asian American adolescents.[23] Parental emphases on "collectivism [and] interdependency," when operationalized with measures of meeting parental expectations for academic or career achievement, are found to be correlated with psychological distress in Asian American children.[24]

Self-Stigma and Self-Concealment: Difficulty Seeking Help

The greater amounts of stress placed on Asian American children makes it all the more troubling that disclosure rates and utilization of mental health resources are lowest in this demographic. The fact that Asian Americans are less likely to seek help for their mental health makes them more likely to wait until they have developed severe somatic symptoms or even a crisis situation before they reach out for mental health support.[25-27] Self-stigma, an internalization of negative societal beliefs around mental health, is already prevalent in the general population, where negative images of mental illness lower individuals' internalized self-concept, self-esteem, and self-efficacy.[28] In this way, seeking help is internalized as a feeling of inferiority; over 75% of all respondents to a survey conducted by Vogel et al. (2006) said they would feel "less satisfied with [them]selves," "inadequate," or even "less intelligent" if they were to seek psychological help.

Being Asian American heightens this stigma, with the model minority myth enforcing an idea of remaining silent about one's struggles, creating unresolved issues that build up stress.[29] In fact, Asian Americans have greater mental health stigma and less favorable help-seeking attitudes than European Americans.[30] Stemming from cultural contexts where "excessive self-disclosure and strong emotional expression" are seen as "disruptive acts against collective harmony and family honor," Asian American college students were found to display more self-concealment of potentially distressing personal information than were European Americans.[31] Such self-concealment was additionally negatively correlated with attitudes toward seeking psychological help. However, there is hope: another study found a significant correlation between previous experiences with counseling and "an increased willingness to seek such services in the future" as well as "higher ratings regarding severity of some problems, such as substance abuse."[32] Such an increase demonstrates the potential to counter Asian Americans' tendency to downplay the hardships they are enduring through receiving education that it is healthy rather than shameful to disclose struggles.

Possible Interventions

This finding leads us to a few potential interventions to combat Asian Americans' lack of disclosure regarding mental health conditions. Disseminating education around mental health in Asian American communities is an important step to cultivate healthy conversations between parents and children around mental health.[33,34] This education should highlight incremental preventative care for mental health to prevent further waiting until dire need or crisis to act. To be most effective, this education should also be tailored specifically to Asian American communities by using culturally familiar situations to normalize mental health conditions, medications, and therapy.[35]

One specific intervention tested by Yang et al. (2013) was a process of stereotype disconfirmation in Asian American parents to aid their relationship with their children's mental health experiences. In this experiment, parents were given an opportunity to directly interact with a caregiver who would disconfirm pre-existing stereotypes and unhealthy reactions to their children in order to create healthier relationships and reactions to disclosure in families. For example, specific Chinese "tiger parenting" strategies like using criticism as motivation were countered by demonstrating how this method exacerbates mental health situations. The experiment was found to improve parents' reactions to their children's disclosure, which could help encourage more disclosure. In doing so, the parents reported an importance of seeing direct real-life application of their situation from a teacher who had similar lived experiences to them.

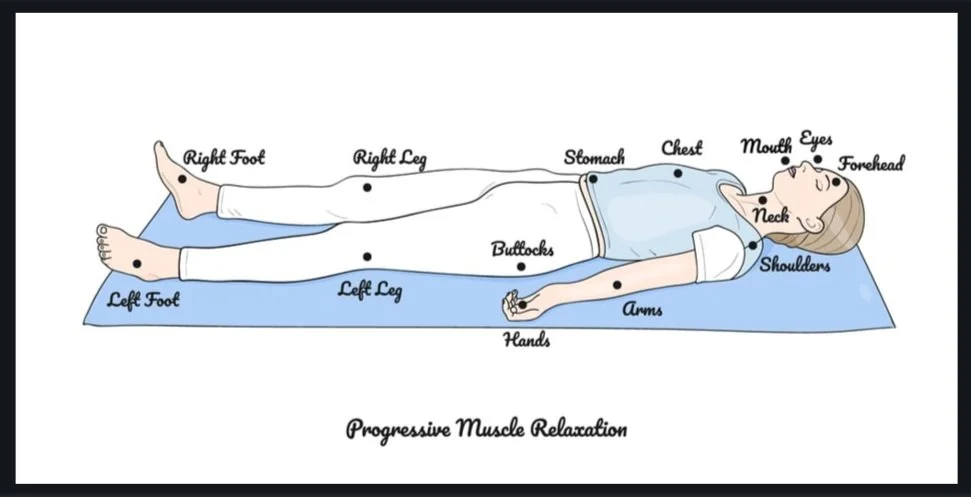

Finally, in the counseling field, we need to address barriers to cross-cultural counseling, which include culture-bound values, class-bound values, and language factors.[36] Because counseling strategies and techniques may force clients to oppose cultural values, particularly in Asian American patients who value restraint of strong feelings, we need to find ways to work within the bounds of culture or compassionately reason why cultural values can be harmful in order to build a healthy therapeutic relationship. By addressing the convergence of stereotypes, historical trauma, and cultural barriers to cross-cultural counseling, therapists can provide more empathetic support to Asian Americans in collaboratively confronting their mental health conditions.

For more information, click here to access an interview with Psychologist Sarah Gaither on race & social identity.

Contributed by: Anna Kiesewetter

Editors: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D. & Brittany Canfield, Psy.D.

References

1 Sue, D. W. (1993, November 30). Asian-American mental health and help-seeking behavior: Comment on Solberg et al. (1994), Tata and Leong (1994), and Lin (1994). Journal of Counseling Psychology. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ487581

2 Masuda, A., & Boone, M. S. (2011, September 21). Mental health stigma, self-concealment, and help-seeking attitudes among Asian American and European American college students with no help-seeking experience - International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling. SpringerLink. Retrieved February 23, 2022, from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10447-011-9129-1

3 Jung, S. (2021, June 18). The model minority myth on Asian Americans and its impact on mental health and the clinical setting. Asian American Research Journal. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2g78c205

4 Lee, S., Juon, et al. (2008, October 18). Model minority at risk: Expressed needs of Mental Health by asian american young adults - journal of community health. SpringerLink. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10900-008-9137-1

5 Ibid.

6 Sue, 1993

7 Ibid.

8 Yang, L. H., et al. (2013, December 6). A brief anti-stigma intervention for ... - sage journals. PubMed. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1363461513512015

9 Sue, 1993

10 Yi, V. (2016, February 9). Model minority myth. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Nationalism. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from https://www.academia.edu/21743155/Model_Minority_Myth

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Sue, 1993

14 Yi, 2016

15 Canady, V. A. (2021, March 26). Field condemns hate‐fueled attacks of Asian Americans, offers MH supports. Wiley Online Library. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mhw.32736

16 Jung, 2021

17 Sue, 1993

18 Jung, 2021

19 Lee et al., 2008

20 Ibid.

21 Choi, Y., et al. (2019, December 16). Disempowering parenting and Mental Health Among Asian American Youth: Immigration and Ethnicity. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0193397319301145

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Lee et al., 2008

26 Jung, 2021

27 Sue, 1993

28 Vogel, D. L., et al. (2006). Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking ... Measuring the Self-Stigma Associated With Seeking Psychological Help. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from https://selfstigma.psych.iastate.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/204/2016/02/SSOSH_0.pdf

29 Lee et al., 2008

30 Masuda & Boone, 2011

31 Ibid.

32 Sue, 1993

33 Lee et al., 2008

34 Sue, 1993

35 Yang et al., 2013

36 Sue, 1993