The Prepper Next Door

In 2011, the television show Doomsday Preppers began airing on National Geographic, bringing mainstream attention to what appeared to be an obscure phenomenon.[1] The series featured “preppers” stockpiling bunkers with enormous amounts of food and ammunition while conducting drills to prepare for apocalyptic events such as an electromagnetic pulse (EMP) destroying modern technology or the collapse of society due to civil war.[2] As this trend became more popular, sales of preserved food surged 700% between 2009 and 2014.[3] Since then, interest in the practice has continued to increase with “prepper” groups uniting on social media and companies churning out the supplies needed to survive a doomsday scenario.

What is Prepping?

Prepping has been defined as, “The management of stockpiled household items in anticipation of market disruption.”[4] Individuals considering themselves preppers may perceive the current structure of society to be a landscape of risk in which the institutions that control access to energy, food, healthcare, shelter, water and waste disposal are associated with risks related to nuclear fallout, toxic pollution, climate change, resource depletion, and potential ecological collapse.[5] Activities of “prepping” tend to revolve around the six core needs of medicine, security, shelter, nutrition, hydration, and hygiene.[6]

Lessons from COVID-19

Smith & Thomas (2021) note that before the COVID-19 pandemic, doomsday prepping was sometimes associated with terms such as paranoia, conspiracy mentality, social dominance orientation, cynicism, and conservatism - but attitudes of the general public changed when COVID-19 lockdowns began in early 2020.[7] Shortages of toilet paper rippled throughout the country as the public frantically panic-shopped while preparing to stay home for an undetermined amount of time.[8] Two years later, supply chain issues related to the pandemic still continue, with 2022 seeing shortages in Sriracha, lumber, baby formula, and cream cheese.[9] To many, the previously-mocked lifestyle of prepping no longer seemed like a wild idea, but rather an intelligent way to prepare for uncertainty that may lie ahead.[10]

The pandemic spurred the immediate reaction of flight from densely-populated urban environments, with Manhattan experiencing a 15-20% reduction in population during the first few months.[11] By the end of 2020, the average new home purchase had shifted an additional 3 miles away from urban centers, though some analysts believe that urban flight may be temporary.[12,13] Some who migrated to rural areas started discovering the joys of hobbies like gardening, cooking from scratch, and creating homemade goods.[14] This shift in priorities and interests, combined with years of rotating shortages often attributed to disastrous events such as Hurricane Ian or Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, worked together to result in a public change in perception towards prepping.[15] Fetterman, (2021) believes this shift is not necessarily unfounded since recent research conducted in Denmark and the US indicates that those who had an interest in prepping were better-equipped psychologically, during the pandemic.[16]

The Surprising Effect of Media on Resilience

The beginning of the millennia produced a fascination with post-apocalyptic worlds, as can be seen by the popularity of shows like The Walking Dead and video games like Fallout 4.[17] While media has at times been credited, or possibly accused, with sewing the idea of individual self-reliance during the apocalypse, Dr. Troy Rondinone, historian of American culture, states these stories also provided narratives of hope by showing that the best chances of survival are through democratic, interracial neighbors selflessly helping each other.[18]

This concept was recently reinforced by research conducted by Scrivner et al., (2021) which found that during the COVID-19 pandemic, those who had engaged with thematically-relevant media (such as pandemic-related media and horror films) demonstrated greater psychological resilience and preparedness.[19] Additionally, horror fans showed greater resilience than fans of the prepper genre (including zombie, apocalyptic, and alien-invasion media) indicating that “trait morbid curiosity” and exposure to frightening fiction may give audiences the opportunity to practice effective coping strategies and results in positive resilience.[20]

Ancient Preppers

While prepping may sound like an extreme response to our current structure of society, historically, there may be precedence across cultures to indicate otherwise. The art of processing and storing food is what allowed humans to survive times of winter or long voyages overseas.[21] When agriculture was being developed, food storage served as a form of risk management that protected against crop failure.[22] To preserve food for winter, humans learned the art of shucking, shelling, boiling, blanching, and canning which gave humanity the benefits of reducing food waste, improving nutrition, and increasing leisure time.[23] Historically, food storage systems were needed to secure an excess amount of food that was greater than what was required for immediate annual household needs, provided sustenance through seasonal or yearly shortages, and allowed an excess amount for trading.[24]

Evidence of the importance of food storage to early humans is supported by research conducted by Blasco et al., (2019) on the Qesem Cave in Israel which found that during the Middle Pleistocene period, butchery techniques indicated that preservation was used for delayed consumption of bone marrow and bone fat.[25] Similarly, in Jordan, evidence gathered from a 19,000-year-old archaeological site showed evidence of gazelle meat being smoked and dried for preservation.[26] Recent evidence has also emerged indicating that prehistoric West Africa used clay pots to assist in the processing and storing of plants 10,000 years ago.[27]

During the Roman Empire, food storage was so advanced that Aelius Aristides, a second century grammarian, described it as the warehouse of the world since Roman consumers not only had access to food from different regions, but they were available year-round.[28] In ancient Peru, stone structures (qolcas) were constructed on the northern face of a mountain where icy wind produced natural refrigeration; they were used as a system of community food storage to help withstand times of bad harvest.[29] In Ireland, hundreds of butter cakes have been found (one dating back as early as 5,000 years ago) in peat bogs which prevented the growth of bacteria and decomposition.[30] Around the same time, China began using salt as one of the most important food preservatives.[31] Considering the long global history of humans storing food to avert shortages, it may not be that unusual that modern humans today have the instincts to engage in a similar behavior.

Prepping Across the Modern World

One unique aspect of prepping in modern America is the emphasis on self-sufficiency, the American ideal of individualism.[32] Some preppers in the US strive for independence and desire to break free from the institutions that regulate access in modern society.[33] Yet the prepping phenomenon is not unique to the United States.

In 2019, it was estimated that one-in-five consumers in Britain were storing medicine, food, and water in preparation for supply chain interruptions related to Brexit (the highly-debated decision for the United Kingdom to leave the European Union).[34] Yeoh (2020) reported that in Singapore, some preppers aim to use a methodical mindset towards preparation which provides a contingency plan for any crises.[35] This point is illustrated by descriptions of a family that is fully prepared with harnesses to quickly escape their 5th floor apartment in the event of a fire, and supplies of oxygen tanks in case a family member tested positive for COVID-19 but needed to wait for medical treatment.[36] It should also be recognized that not all cultures view prepping as an unusual activity. Nakkiah Lui, a First Nations actress and comedian from Australia who created the sitcom Preppers, describes her journey watching shows about entering the world of prepping and thinking, “Being a First Nations person… that idea of survival and prepping for the worst, and survival being part of your history…that’s definitely something I’ve inherited.”[37]

Inherited Instincts or Learned Behavior

With the historical context of food storage and preparedness across cultures, the question can be raised, “Is the act of prepping the result of human instincts or reactions to perceived threats in the environment?” In response to this question, different theories have emerged. Research conducted by Lindstrom et al., (2016) found that in dangerous environments, genetic preparedness and social learning co-evolve simultaneously.[38] In both humans and animals, preparedness behaviors have the tendency to reduce foraging efficiency, but can result in higher rates of survival which indicate the trade-off that needs to take place between safety and flexibility.[39]

Life History Theory (LHT) is an explanatory framework for behavior that integrates the perspectives of evolutionary, social developmental, and ecological theories while considering the amount of effort needed to invest in achieving a goal and the trade-offs that are required.[40] Living in an unpredictable environment tends to lead to activities that are focused on the present and may involve riskier behavior, while living in a more predictable environment leads to behavior that is more focused on long-term strategies such as lower levels of risk-taking and greater regard for social rules.[41] Since emergency preparedness requires a focus on long-term strategies, it tends to be adapted by those with a slower life history; those with a faster life history may experience greater fear of future disasters.[42]

The Instinct Theory of Motivation suggests the environment plays the role of triggering the cognitive abilities that are produced through natural selection.[43] Theorists from the Santa Barbara School of Evolutionary Psychology take a nativist outlook to cognitive instinct, teaching that cognitive mechanisms are hardwired and inherited genetically from our ancestors through the natural selection of genes.[44] In contrast, the California School Cultural Evolutionists endorse the view that our psychology is primarily culturally inherited, through social learning that may be underpinned by cognitive instincts.[45] Turner & Walmsley, (2021) state the view that cultural learning and social cognition are the result of a substantial amount of genetic inheritance.[46]

The way a person views apocalyptic scenarios may also offer insight into people’s beliefs about humans and society.[47] For example, it may be easier for a person to express that they would be fearful of how people would behave in an apocalyptic world than to say that they distrust people.[48]

Prepping and Mental Health

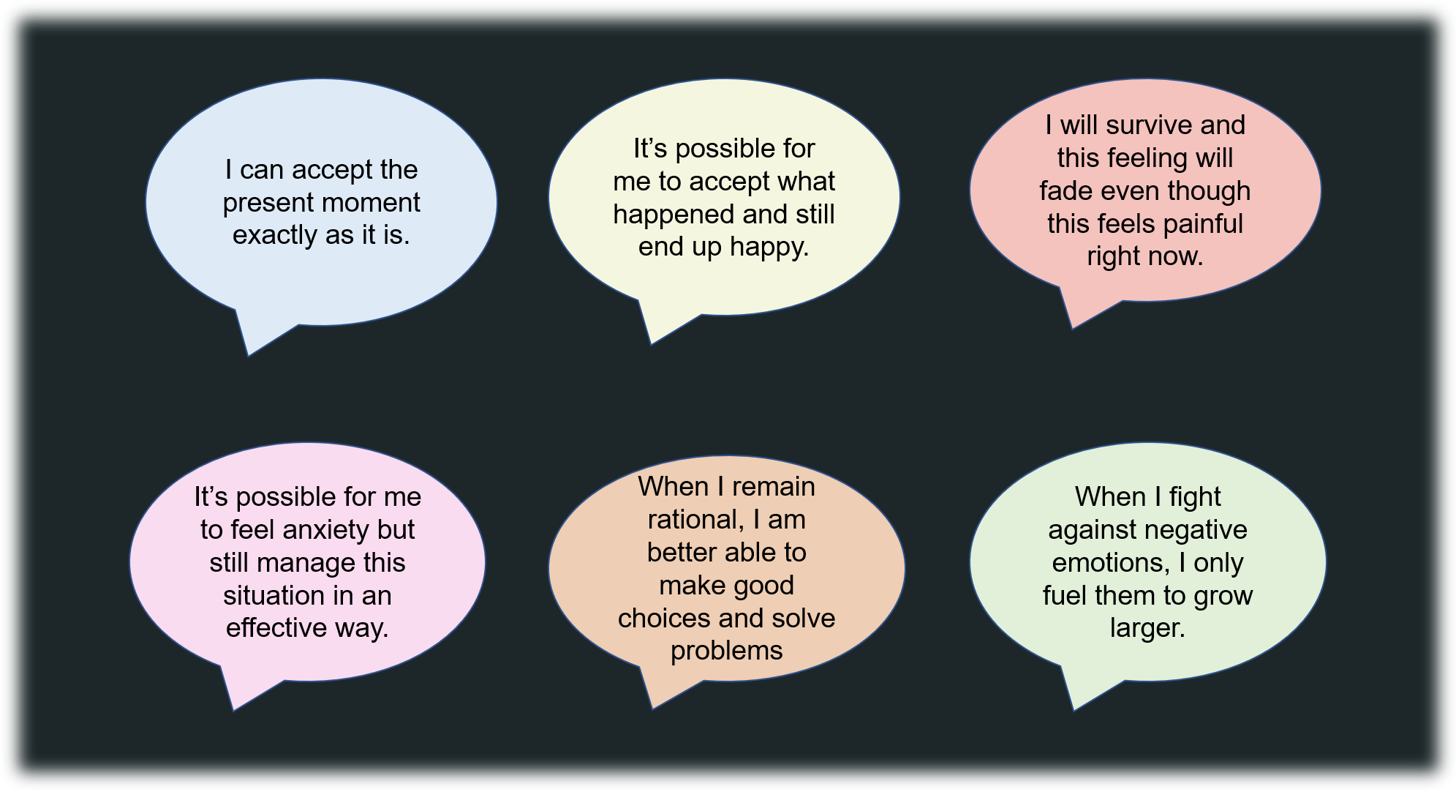

The historic and genetic aspects of this topic all work to raise the question, “Is prepping a psychologically healthy behavior?” Mills (2019) presents an understanding that prepping is a response generated by general anxiety about a variety of potential disasters in the future, which are fueled by reports and government warnings in mainstream media.[49] However, fieldwork interviewing preppers found that the majority of concerns were non-apocalyptic and focused instead on temporary disasters.[50] In terms of existential psychology, prepping thoughts and behavior may be an outlet for processing feelings of uncertainty.[51] To address these concerns, self-sufficiency can serve as an emotional management strategy that channels the emotional energy generated over risk into the more pleasurable activities of building water systems, gardening, and canning.[52]

While analyzing the events of 2020, which included the recent pandemic, the storming of the Capitol, protests for racial justice, a record-breaking hurricane season, and unprecedented freezes in Texas that left many without power, Psychologist Adam Fetterman determined that the majority of time people were cooperative and helped each other during these events.[53] Dr. Fetterman, who states that he previously believed prepping behavior to be a little irrational, found that while the COVID-19 pandemic showed that cynical views on human nature were largely unwarranted, there was some legitimacy about concerns to the supply chain.[54] This raises the question of how real threats to temporary access to resources can be addressed in a way that is psychologically healthy.

Psychologist Marty Nemko recommends avoiding hoarding, but stocking enough supplies to last a month, then supplementing them with smaller purchases as needed.[55] He recommends prioritizing water, food, medication, first aid supplies, hand-cranked/solar radios and flashlights, motor oil, cash, and back-up internet through a cell phone provider.[56] Taking these basic precautions is considered a productive way to take charge and effectively address concerns about the supply chain.

While preparing for potential disasters is warranted, it is still best to make sure it does not become an all-encompassing preoccupation. A person should consider speaking with a licensed mental health professional if worrying about potential disasters becomes obsessive, anxiety is interrupting eating or sleeping, preparations have negative impacts on a person’s finances, personal relationships are being impacted, or a person feels too overwhelmed to take the steps necessary to prepare for a future event.

Contributed by: Theresa Nair

Editor: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D.

REFERENCES

1 Doomsday preppers. IMDb Web site. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2069270/. Accessed January 6, 2023.

2 Doomsday preppers. National Geographic Web site. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/tv/shows/doomsday-preppers. Updated 2023. Accessed January 6, 2023.

3 Mills MF. Obamageddon: Fear, the Far Right, and the Rise of “Doomsday” Prepping in Obama’s America. Journal of American studies. 2021;55(2):336-365. doi:10.1017/S0021875819000501

4 Kerrane B, Kerrane K, Bettany S, Rowe D. (Invisible) Displays of Survivalist Intensive Motherhood among UK Brexit Preppers. Sociology (Oxford). 2021;55(6):1151-1168. doi:10.1177/0038038521997763

5 Ford A. Emotional Landscapes of Risk: Emotion and Culture in American Self-sufficiency Movements. Qualitative sociology. 2021;44(1):125-150. doi:10.1007/s11133-020-09456-x

6 Mills (2021)

7 Smith N, Thomas SJ. Doomsday Prepping During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in psychology. 2021;12:659925-659925. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.659925

8 Fisher M. Flushing out the true cause of the global toilet paper shortage amid coronavirus pandemic. The Washington Post Web site. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2387125885?accountid=11243&parentSessionId=tet7dRjqBnZ4ODYs%2BJHwOpbh3ygcM8U2IzS3hGUGX6I%3D. Updated 2020. Accessed January 10, 2023.

9 Hernandez D, Wagh M. These 19 items are in short supply due to COVID-related supply chain issues. Popular Mechanics Web site. https://www.popularmechanics.com/culture/g38674719/covid-shortages/. Updated 2022. Accessed January 4, 2023.

10 Smith & Thomas (2021)

11 Haseltine W. Urban flight due to covid-19 is temporary, not permanent. Forbes Web site. https://www.forbes.com/sites/williamhaseltine/2020/12/21/urban-flight-due-to-covid-19-is-temporary-not-permanent/?sh=22faaa154cd5. Updated 2020. Accessed January 6, 2023.

12 Malone T. Is the pandemic-induced move to the suburbs over? CoreLogic Web site. https://www.corelogic.com/intelligence/is-the-pandemic-induced-move-to-the-suburbs-over/. Updated 2023. Accessed January 12, 2023.

13 Haseltine (2020)

14 Farrer L. 4 reasons rural destinations are winning in the great relocation. Forbes Web site. https://www.forbes.com/sites/laurelfarrer/2022/03/24/4-reasons-rural-destinations-are-winning-in-the-great-relocation/?sh=885ead733d84. Updated 2022. Accessed January 12, 2023.

15 Little A. The preppers were right all along. Bloomberg Web site. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-11-06/climate-change-is-launching-a-new-generation-of-preppers. Updated 2022. Accessed January 12, 2023.

16 Fetterman A. Were the doomsday preppers right? Psychology Today Web site. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/it-s-all-metaphor/202104/were-the-doomsday-preppers-right. Updated 2021. Accessed January 3, 2023.

17 Fetterman A., Rutjens B., Landkammer F, Wilkowski B. On Post-apocalyptic and Doomsday Prepping Beliefs: A New Measure, its Correlates, and the Motivation to Prep. European journal of personality. 2019;33(4):506-525. doi:10.1002/per.2216

18 Rondinone T. Has hollywood prepped us for the pandemic? Psychology Today Web site. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-asylum/202003/has-hollywood-prepped-us-the-pandemic. Updated 2020. Accessed January 4, 2023.

19 Scrivner C, Johnson JA, Kjeldgaard-Christiansen J, Clasen M. Pandemic practice: Horror fans and morbidly curious individuals are more psychologically resilient during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;168:110397. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0191886920305882. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110397.

20 Ibid.

21 Temple N. How humanity has changed the food it eats. BBC Web site. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20210514-how-humanity-has-changed-the-food-it-eats. Updated 2021. Accessed December 19, 2022.

22 Kuijt I. What Do We Really Know about Food Storage, Surplus, and Feasting in Preagricultural Communities? Current anthropology. 2009;50(5):641-644. doi:10.1086/605082

23 Temple (2021)

24 Kujit (2009)

25 Blasco R, Rosell J, Arilla M, et al. Bone marrow storage and delayed consumption at Middle Pleistocene Qesem Cave, Israel (420 to 200 ka). Science advances. 2019;5(10):eaav9822-eaav9822. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aav9822

26 Alex B. How did ancient people keep their food from rotting? Discover Web site. https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/how-did-ancient-people-keep-their-food-from-rotting. Updated 2020. Accessed January 4, 2023.

27 Dunne J. Chemical traces in ancient west african pots show a diet rich in plants. The Conversation Web site. https://theconversation.com/chemical-traces-in-ancient-west-african-pots-show-a-diet-rich-in-plants-177579. Updated 2022. Accessed January 6, 2023.

28 Cheung C. Managing food storage in the roman empire. Quaternary International. 2021;597:63-75. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040618220304584. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2020.08.007.

29 Liendo Tagle I. In peru, ancient food technologies revived in pursuit of future security. Mongrabay Web site. https://news.mongabay.com/2021/09/in-peru-ancient-food-technologies-revived-in-pursuit-of-future-security/. Updated 2021. Accessed January 4, 2023.

30 Alex (2020)

31 Huebbe P, Rimbach G. Historical Reflection of Food Processing and the Role of Legumes as Part of a Healthy Balanced Diet. Foods. 2020;9(8):1056. Published 2020 Aug 4. doi:10.3390/foods9081056

32 Ford (2021)

33 Ibid.

34 Kerrane et al. (2021)

35 Yeoh G. Ever ready for an apocalypse: Inside the minds of doomsday preppers in singapore. Channel News Asia (CNA) Web site. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/cnainsider/always-ready-apocalypse-inside-minds-doomsday-preppers-singapore-629296. Updated 2020. Accessed January 6, 2023.

36 Ibid.

37 Connaughton M. Nakkiah lui on public shaming and her doomsday comedy: ‘Prepping for the worst is something i’ve inherited’. The Guardian Web site. https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2021/nov/08/nakkiah-lui-on-public-shaming-and-her-doomsday-comedy-prepping-for-the-worst-is-something-ive-inherited. Updated 2021. Accessed January 10, 2023

38 Lindström, Selbing, I., & Olsson, A. (2016). Co-evolution of social learning and evolutionary preparedness in dangerous environments. PloS One, 11(8), e0160245–e0160245. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160245

39 Ibid.

40 Kruger DJ, Fernandes HBF, Cupal S, Homish GG. Life History Variation and the Preparedness Paradox. Evolutionary behavioral sciences. 2019;13(3):242-253. doi:10.1037/ebs0000129

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 Turner CR, Walmsley LD. Preparedness in cultural learning. Synthese (Dordrecht). 2021;199(1-2):81-100. doi:10.1007/s11229-020-02627-x

44 Ibid.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid.

47 Fetterman et al. (2019)

48 Ibid.

49 Mills MF. Preparing for the unknown... unknowns: “doomsday” prepping and disaster risk anxiety in the United States. Journal of risk research. 2019;22(10):1267-1279. doi:10.1080/13669877.2018.1466825

50 Ibid.

51 Fetterman et al. (2019)

52 Ford (2021)

53 Fetterman (2021)

54 Ibid.

55 Nemko M. Should you prep for supply chain shortage? updated 4/15/20. Psychology Today Web site. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/how-do-life/202004/should-you-prep-supply-chain-shortage-updated-41520. Updated 2020. Accessed January 4, 2023.

56 Ibid.