An Overwhelming Sense of Loss

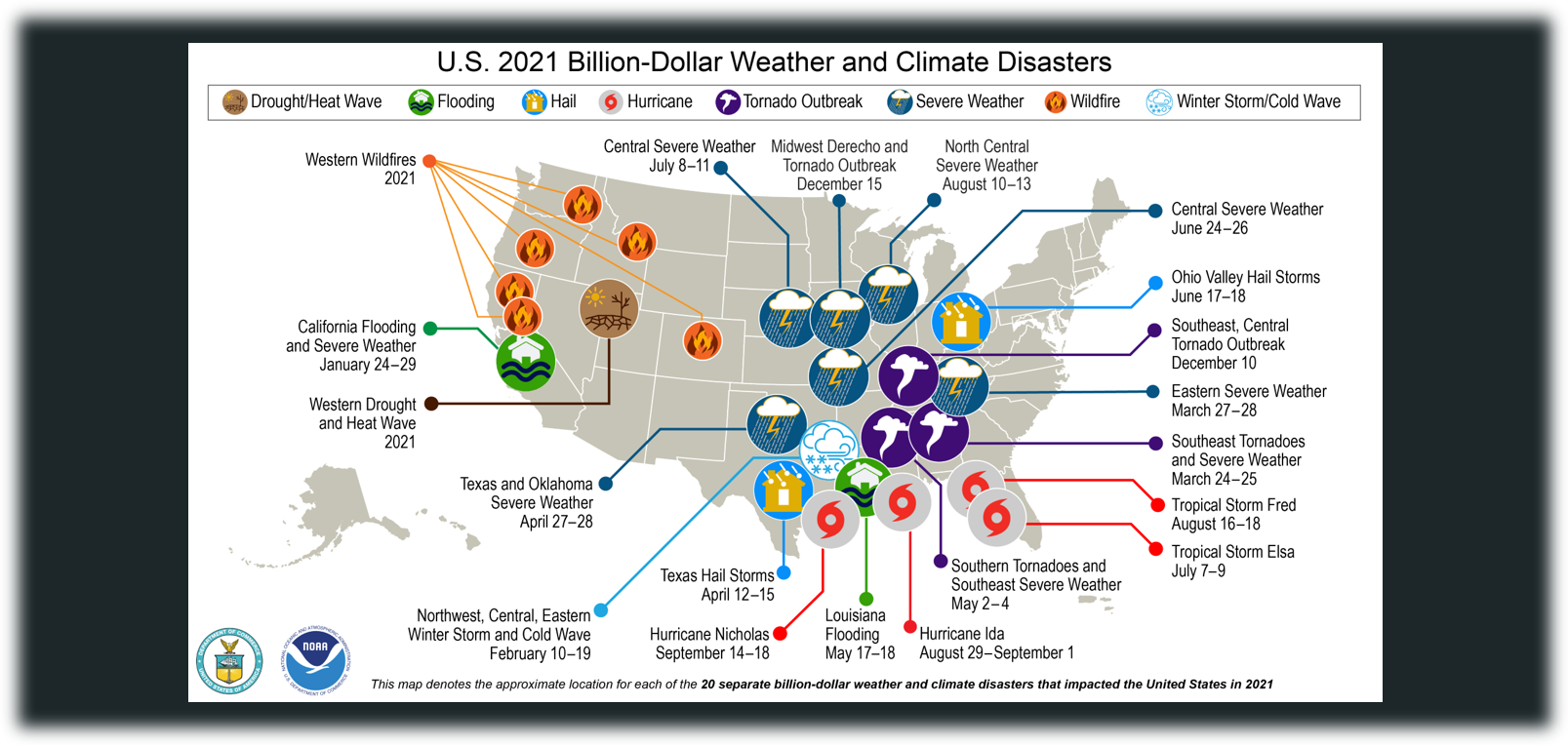

As families in Central Florida struggle to recover from Hurricane Ian, the Bolt Creek Fire continues burning in Washington State.[1,2] The incidence of natural disasters is on the rise, with the years 2020 and 2021 ranking as the two years with the highest recorded number of disasters in the United States.[3] Devastating disasters in 2021 included 20 billion-dollar events ranging from a derecho (a widespread, damaging windstorm that moves across vast distances) in the Midwest, an extreme cold wave event in Texas, multiple wildfires across the west coast, and four tropical cyclones in the Southeast.[4]

In 2021, the United States experienced record-smashing 20 weather or climate disasters that each resulted in at least $1 billion in damages. NOAA map by NCEI.

Image source: Smith (2022)[5]

All regions of the country are affected by some form of natural disaster and exposure to these events take a toll on mental health. In the immediate aftermath of a disaster, survivors are often left in a state of shock while struggling with anxiety over safety and recovery.[6,7] Even those who are not directly impacted by a disaster may still experience trauma due to the potential threat of their area being affected, evacuating to avoid the danger, having loved ones in harm’s way, or watching the event unfold on the news. While every person reacts to these experiences differently, it is normal for disasters to have some degree of impact on mental health.[8] Understanding these reactions, and when to seek help from others, is an important step in the process of recovery.

Common Reactions to Disasters

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, more commonly referred to as PTSD, is the most commonly studied psychopathology following a disaster.[9] After Hurricane Maria, a sample study of survivors who relocated to Florida from Puerto Rico found that two-thirds showed significant symptoms of PTSD.[10] Those suffering from PTSD may experience flashbacks of the event, detachment from others, reactions to loud sounds, avoiding reminders of the disaster, and restless sleep from nightmares.[11] These symptoms may naturally decline over time, but a person experiencing ongoing symptoms may benefit by seeking treatment from professionals who can provide support through Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) and prescribe medication if needed.[12]

Depression – Depression is another common reaction to a disaster.[13] Symptoms of major depressive disorder, or clinical depression, may include: feeling sad, empty or hopeless; loss of interest in enjoyable activities; sleeping too much or too little; slowed thinking or speaking; feeling guilty or worthless; unexplained physical pain; increases or decreases in appetite; emotional outbursts; and thoughts of suicide.[14] A sense of loss is normal after a disaster, and these feelings may fade with time, but if symptoms last for several days, or are impeding the recovery process, it may be time to speak to a mental health professional.[15] If a person is depressed and contemplating suicide, they should seek immediate help by contacting the national suicide hotline at 988, calling 911, or proceeding to the nearest emergency room.[16]

Anxiety – The immediate time following a disaster can be filled with fear and uncertainty of the future.[17] Disasters can activate the “flight or fight” response, which sends cortisol and adrenaline rushing through the body to help a person react more quickly.[18,19] This is a normal response to a threatening situation, and it may be difficult to differentiate between a normal rush of adrenaline following an event and the development of anxiety.[20] While occasional experiences of anxiety are considered normal throughout life (and especially following a disaster) if the symptoms persist for months, it could be a sign that a person is developing Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), or another phobia-related disorder.[21] If a person begins experiencing persistent feelings of dread, worrying uncontrollably, constantly being “on-edge,” headaches, stomach aches, difficulty sleeping, or constant thoughts of a specific fear, it may be time to seek professional guidance to determine if therapy and/or medication would be beneficial.[22]

Insomnia – Insomnia is a sleep disorder that can interfere with a person’s ability to either fall asleep or stay asleep.[23] Difficulty sleeping is common after disasters, not only because it can manifest by itself, but also because it is believed to be associated with the development of other disorders including PTSD and depression.[24] A 2019 study on survivors of disasters in Korea found that those who were widowed, divorced, elderly, separated, and in pain were the most likely to experience less than 5 hours of sleep per night in the following years.[25] If a person finds themselves experiencing insomnia, there are natural remedies that can be tried including relaxation training, stimulus control therapy, sleep environment improvement, sleep restriction, sleep hygiene, biofeedback, and remaining passively awake.[26] If these techniques do not work, it may be necessary to speak with a professional to see if medication is needed or if the insomnia may be caused by a more serious condition.

Mood Swings – Changes in emotions are common after a disaster and may include numbness, sadness, anxiety, irritability, withdrawal, grief, helplessness, and anger.[27] Survivors often experience uncontrollable crying or bursts of anger.[28] It is important to be patient when working through grief as feelings can fluctuate, so it is normal to feel empowered one day and overwhelmed the next.[29] To help process feelings, talking to family members or loved ones may be helpful, but professional help should be sought if the feelings become overwhelming or can only be controlled with drugs or alcohol.[30]

Solastalgia – This phenomenon describes the severing of a person from their connection to their homeland and it can arise when the landscape is changed by droughts, wildfires, or pollutants.[31] Solastalgia is a relatively new term, first created by Glen Albrecht and introduced at the Ecohealth Conference in 2003, to help describe the relationship between humans and the rapidly changing environment.[32] “The feeling of homesickness whilst still at home,” describes the feeling of longing for a home that no longer exists.[33] Though research on solastalgia is relatively new, if a person is struggling to adapt to environmental changes and is unsure of how to move forward, cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, psychodynamic therapy, antidepressants, and anti-anxiety medication may be beneficial when working with a mental health provider.[34]

Ecological Grief - Ecological grief refers to the mourning that occurs when a person’s environment and lifestyles are affected by climate change.[35] While this grief may affect anyone, it is believed to disproportionately affect those who live in traditional indigenous communities and others who work with the land as part of their culture and survival.[36] Ecological grief can be associated with physical losses, but also with a loss of knowledge since teachings passed down through families for generations may no longer be applicable to the changing environment.[37] This grief can manifest as mood disorders, violence, psychiatric hospitalizations, substance abuse, emotional reactions, suicide ideation, and ecological anxiety.[38] When processing ecological grief, it is recommended to connect with others who are experiencing similar grief, look for productive ways to move forward, and find a licensed mental health provider who is trained to address climate-related concerns.[39]

Eco-anxiety – The American Psychiatric Association describes eco-anxiety as, “a chronic fear of environmental doom.”[40] It differs from ecological grief in that it is focused on the forward-thinking practice of worrying about future environmental changes as opposed to mourning an already lost way of life.[41] Negative reactions associated with eco-anxiety include feelings of helplessness, panic, guilt, weakness, sadness, numbness, fear and anger; though at times, eco-anxiety can also have the positive effect of motivation to act.[42] While it is normal to worry about future environmental changes when recovering from a disaster, if the anxiety is severe and cannot be successfully managed at home, it may be helpful to speak with a mental health care professional or family doctor.[43]

Self-Care

While people may not be able to directly stop the natural disasters occurring in their area, they can take steps to protect their mental health. The CDC recommends getting enough sleep, eating well, exercising and avoiding harmful substances such as alcohol and tobacco.[44] After a disaster people will often feel physically and mentally drained, experience changes in sleep patterns or appetite, argue with friends and family, feel lonely, and get frustrated easily, but many of these symptoms should diminish over time.[45] The American Red Cross states that human beings are designed to be naturally resilient, so many people can find successful ways of coping.[46] Each person reacts uniquely in response to disasters, and symptoms may manifest differently,[47] but the following coping techniques have been found to be beneficial when recovering from disasters:

Talk it Out - When families and individuals are displaced, it can affect their overall sense of community.[48] Finding someone that feels safe to talk to can help process feelings about a disaster.[49] Spending time helping others in the community (such as neighbors, family, or friends) can help to build trust and make people realize that they are not alone in their experiences.[50] It may help to look for support from others who have survived trauma in the form of a support group conducted by trained professionals.[51]

Stay Informed - When people feel they are missing information, they may become stressed or nervous, so schedule a time to regularly get updated information from reliable sources.[52] Many organizations provide resources to deal with the effects of disasters (e.g., FEMA, The Salvation Army, and Feeding America), so make time to become educated about the resources available and what types of services are offered.[53]

Relax - Engage in nurturing, relaxing activities that are enjoyable.[54] Relaxation exercises can include yoga, breathing exercises, listening to music, walks in nature, meditation, swimming or stretching.[55]

Create - Creative activities can help to express feelings after a disaster.[56] These can include painting, playing music, or baking. Writing may also help to process a sense of loss or concerns about future safety.[57]

Volunteer - Volunteering in a community is a way for a person to give back and feel they are making a positive contribution by helping others.[58] It can relieve stress by causing a person to stop thinking about their own problems for a while, put a new perspective on the situation, feel less alone, lift one’s mood, and feel better about themselves.[59]

Exercise - Use physical exercise as a means of reducing stress.[60] Engaging in exercise, such as running, swimming, or weightlifting, can help to relieve physical tension, improve self-esteem, and regain a sense of self-control.[61]

Eat, Hydrate & Rest - Make sure to not only eat a balanced diet, but also drink enough water to stay hydrated.[62] Get adequate rest to take a break both physically and mentally.[63] If a person finds themselves waking up at night, and unable to fall back asleep, it may be beneficial to try briefly writing about what is on their mind to process the thoughts.[64]

Stick to a Schedule - Creating a daily schedule or routine, such as eating healthy meals and sleeping at regular times, is a way to regain a sense of normalcy.[65] Remember to schedule breaks and do things that are enjoyable.[66] Avoid constant or frequent exposure to hearing about or seeing images of the crisis because it may increase anxiety and take away attempts at returning to a sense of normalcy.[67]

Set Goals - Setting short-term goals can help structure time and allow a person to focus on the present instead of getting lost in thought.[68] Develop a recovery plan and stick to it; focus on making progress by prioritizing which problems to tackle and breaking them down into small steps that are easy to accomplish.[69]

Focus on the Positive - Take time to be grateful for anything that is positive in the situation instead of dwelling on the dread of what might come next.[70] Work on reframing thoughts from the negative to the positive; instead of thinking, “I can’t do this,” think, “What steps can I take to do this?”[71]

Grieve - Grief can occur due to loss of family, friends, co-workers, job, loved ones, home, pets, possessions, or life quality.[72] Creating a ritual or ceremony to honor what was lost can help to express grief, affirm relationships/values, and move on with life.[73]

Behaviors to Avoid

Avoid negative behaviors that may give an immediate relief as opposed to dealing with the problem.[74] These behaviors include substance abuse, overworking, self-isolation, and overeating.[75] When recovering from a disaster, everyone in the area will be experiencing significant stress, so it’s important to be patient with not only yourself, but also others.[76] Anger is a normal reaction when recovering from disasters, but to preserve healthy relationships, it may be necessary to take a step back and calm down in order to think clearly.[77]

When to Seek Professional Support

The American Red Cross recommends getting professional support if any of these symptoms are experienced for two weeks or longer:[78]

Bursts of anger

Feeling hopeless

Crying spells

Loss of interest in things

Difficulty eating or sleeping

Fatigue

Headaches

Stomach aches

Avoiding friends/family

Feelings of guilt

If stress from an event is impacting daily life, reach out to a doctor, counselor, therapist, psychiatrist, or clergy member for support.[79] If symptoms such as anger, insomnia, irritability, or anxiety persist, speak with a doctor or mental health provider to inquire if you should be prescribed medication, even for a short duration, following a natural disaster.[80] If symptoms do not improve, or seem to be getting worse, contact a licensed mental health professional for further guidance.[81]

Contributed by: Theresa Nair

Editor: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D.

REFERENCES

1 Tolan C, Devine C. Lack of flood insurance in hard-hit central florida leaves families struggling after hurricane ian. CNN Web site. https://www.cnn.com/2022/10/09/us/hurricane-ian-central-florida-flood-insurance-invs/index.html. Updated 2022. Accessed Oct 10, 2022.

2 Staff ST. Wildfire evacuations, stevens pass closure remain amid bolt creek fire. The Seattle Times Web site. https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/wildfire-evacuations-stevens-pass-closure-remain-amid-bolt-creek-fire/. Updated 2022. Accessed Oct 10, 2022.

3 Smith A. 2021 U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters in historical context | NOAA climate.gov. Climate.gov Web site. http://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2021-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters-historical. Updated 2022. Accessed Oct 14, 2022.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Makwana N. Disaster and its impact on mental health: A narrative review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(10):30903095. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6857396/. Accessed Oct 14, 2022. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_893_19.

7 Disaster behavioral health. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Web site. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/abc/Pages/disaster-behavioral.aspx. Updated 2020. Accessed Oct 14, 2022.

8 Felix ED, Afifi W. THE ROLE OF SOCIAL SUPPORT ON MENTAL HEALTH AFTER MULTIPLE WILDFIRE DISASTERS: Social Support and Mental Health After Wildfires. Journal of community psychology. 2015;43(2):156-170. doi:10.1002/jcop.21671

9 Lee J, Kim S, Kim J. The impact of community disaster trauma: A focus on emerging research of PTSD and other mental health outcomes. Chonnam Med J. 2020;56(2):99-107. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7250671/. Accessed Oct 14, 2022. doi: 10.4068/cmj.2020.56.2.99.

10 Espinel Z, Galea S, Kossin JP, Caban-Aleman C, Shultz JM. Climate-driven Atlantic hurricanes pose rising threats for psychopathology. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(9):721-723. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30277-9

11 Psychiatry.org - what is posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)? https://www.psychiatry.org:443/patients-families/ptsd/what-is-ptsd. Updated 2020. Accessed Oct 14, 2022.

12 Ibid.

13 Stuart M. Understanding depression following a disaster. The University of Arizona Cooperative Extension Website. https://extension.arizona.edu/sites/extension.arizona.edu/files/pubs/az1341h.pdf. Accessed Oct 14, 2022.

14 Depression (major depressive disorder) - symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic Web site. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/symptoms-causes/syc-20356007. Accessed Oct 14, 2022.

15 Coping with a disaster or traumatic event. Center for Disease Control (CDC) Web site. https://emergency.cdc.gov/coping/selfcare.asp. Updated 2019. Accessed Oct 17, 2022.

16 Mayo Clinic Web (2022)

17 Coping with disaster. Mental Health America Website. https://www.mhanational.org/coping-disaster. Accessed Oct 14, 2022.

18 Sheikh K. Natural disasters take a toll on mental health. Brain Facts Web site. https://www.brainfacts.org:443/diseases-and-disorders/mental-health/2018/natural-disasters-take-a-toll-on-mental-health-062818. Updated 2018. Accessed Oct 14, 2022.

19 Learn the difference between high anxiety and an adrenaline rush | first responder wellness. . 2022. https://www.firstresponder-wellness.com/learn-the-difference-between-high-anxiety-and-an-adrenaline-rush/. Accessed Oct 14, 2022.

20 Ibid.

21 Anxiety disorders. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Website. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders. Accessed Oct 15, 2022.

22 Ibid.

23 Ghahari J. Insomnia. Seattle Anxiety Specialists, PLLC: Psychiatry & Psychology Web site. https://seattleanxiety.com/insomnia. Accessed Oct 15, 2022.

24 Disturbed sleep linked to mental health problems in natural disaster survivors: Study is the first to describe sleep health consequences of the 2010 earthquake in haiti. ScienceDaily Website. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/06/190607140446.htm. Updated 2019. Accessed Oct 15, 2022.

25 Kim Y, Lee H. Sleep problems among disaster victims: A long-term survey on the life changes of disaster victims in korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8004935/. Accessed Oct 15, 2022. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063294.

26 Ghahari (2022)

27 Stress reactions and self-care strategies after a traumatic event. Cigna Website. https://www.cigna.com/knowledge-center/stress-after-disaster. Accessed Oct 10, 2022.

28 Taking care of your emotional health after a disaster. Red Cross Website. https://www.redcross.org/content/dam/redcross/atg/PDF_s/Preparedness___Disaster_Recovery/General_Preparedness___Recovery/Emotional/Recovering_Emotionally_-_Large_Print.pdf. Accessed Oct 10, 2022.

29 Cigna (2022)

30 Emotional impact of disasters. txready.org Web site. https://texasready.gov/be-informed/mental-health/emotional-impact-of-disasters.html. Accessed Oct 15, 2022.

31 Kenyon G. Have you ever felt ‘solastalgia’? https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20151030-have-you-ever-felt-solastalgia. Updated 2015. Accessed Oct 15, 2022.

32 Albrecht G, Sartore G, Connor L, et al. Solastalgia: The distress caused by environmental change. AUSTRALAS PSYCHIATRY. 2007;15:S95-S98. doi: 10.1080/10398560701701288.

33 To P, Eboreime E, Agyapong VIO. The Impact of Wildfires on Mental Health: A Scoping Review. Behavioral sciences. 2021;11(9):126-. doi:10.3390/bs11090126

34 Vanbuskirk S. What is solastalgia? Verywell Mind Website. https://www.verywellmind.com/solastalgia-definition-symptoms-traits-causes-treatment-5089413. Updated 2021. Accessed Oct 15, 2022.

35 To et al. (2021)

36 Heid M. Ecological grief: What it is, what causes it, and how to cope. EverydayHealth.com Web site. https://www.everydayhealth.com/emotional-health/whats-the-difference-between-eco-anxiety-and-ecological-grief/. Updated 2022. Accessed Oct 15, 2022.

37 Ibid.

38 Aylward B, Cooper M, Cunsolo A. Generation climate change: Growing up with ecological grief and anxiety. Psychiatric News. 2021. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2021.6.20. Accessed Oct 15, 2022. doi: 10.1176/appi.pn.2021.6.20.

39 Heid (2022)

40 Huizen J. Eco-anxiety: What it is and how to manage it. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/327354. Updated 2019. Accessed Oct 15, 2022.

41 Heid (2022)

42 Coffey et al. (2021)

43 Huizen (2019)

44 CDC (2019)

45 Red Cross (2022)

46 Ibid.

47 Kim & Lee (2021)

48 Felix & Afifi (2015)

49 Recovering emotionally from disaster. American Psychological Association Web site. https://www.apa.org/topics/disasters-response/recovering. Updated 2013. Accessed Oct 12, 2022.

50 Self-care after disasters. VA.gov | veterans affairs. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/gethelp/disaster_selfcare.asp. Accessed Oct 10, 2022.

51 American Psychological Association (2013)

52 CDC (2019)

53 Morganstein J. Psychiatry.org - coping after disaster. American Psychiatric Association Web site. https://psychiatry.org:443/patients-families/coping-after-disaster-trauma. Updated 2019. Accessed Oct 12, 2022.

54 Cigna (2022)

55 Self care and self-help following disasters - national center for post traumatic stress disorder orange county, california. Self Care And Self-Help Following Disasters - National Center for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Orange County, California Web site. https://orange.networkofcare.org/mh/library/article.aspx?id=3113. Accessed Oct 9, 2022.

56 American Psychological Association (2013)

57 Cigna (2022)

58 Orange County (2022)

59 Veterans Affairs (2022)

60 Cigna (2022)

61 Orange County (2022)

62 Red Cross (2022)

63 Ibid.

64 Coping tips for traumatic events and disasters. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Web site. https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/disaster-distress-helpline/coping-tips. Updated 2022. Accessed Oct 17, 2022.

65 Cigna (2022)

66 CDC (2019)

67 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2022)

68 Cigna (2022)

69 Veterans Affairs (2022)

70 Cigna (2022)

71 Veterans Affairs (2022)

72 Ibid.

73 Ibid.

74 Orange County (2022)

75 Ibid.

76 Red Cross (2022)

77 Veterans Affairs (2022)

78 Red Cross (2022)

79 CDC (2019)

80 Orange County (2022)

81 Ibid.