“Working 9 to 5, what a way to make a living

Barely getting by, it's all taking and no giving

They just use your mind, and they never give you credit

It's enough to drive you crazy if you let it”[1]

Introduction

“9-5” by Dolly Parton, a hit that has remained popular to this day, is upbeat, bouncy, and extremely easy to dance to. However, the content of the song itself is not quite so lighthearted. For many working adults in this country, a 9-5 job indeed has the potential to be crazy-making despite barely getting one from bill to bill. Parton, in her more recent song based on the 1980 classic, sings that she staves off the craziness with her passions after work, from 5-9, by doing “somethin’ that gives life its meanin,’”[2]. For many, however, that is not an easy feat: If the “crazy” in question is one of burnout, one is precisely incapable of doing more. We may associate the “crazy” Parton mentions in this song with burnout, a truly maddening condition that can be extremely debilitating if not treated.

The symptoms of burnout can include utter physical and emotional exhaustion, a lack of motivation or general desire, or an incapacity to empathize or care about things as one once did. These effects can take over every part of one’s life. To address this intensity and immense scope, there is no shortage of self-help books and blog posts devoted to burnout, written by everyone from psychologists to mommy-bloggers. Some jobs offer vacation benefits or required sabbaticals to force people to take a break and deal with their symptoms of burnout. Despite widespread efforts to teach people how to recognize the signs of burnout and what to do about it, it seems to continue unabated.

One reason may be burnout itself: Who has the bandwidth to work on their overwork? Another reason could be a culture of fatalism/cynicism. In conversations about burnout, both clinically and colloquially, there is the tendency to talk about the condition as a seemingly inevitable state we all should expect in our adult and working lives. I aim to combat that trend. In what follows, I propose framing burnout as something that is not inevitable. Thus, rather than merely asking how to mitigate or manage it, I inquire how one might go about preventing it. Play, with its immersive qualities, will become a main focus. First, however, I will track the origins of burnout in our economic and social history to point out that burnout has an origin before which it was not commonplace. This can teach us what contributes to the condition and help counteract the narrative of inevitability. Another narrative deserving our scrutiny is the framing of burnout as an inconvenience, another hurdle to getting work done, as opposed to a severe health hazard. Within this narrative, burnout poses as a mere distraction from our productivity, and its insidious effects on our health goes unrecognized. Understanding why burnout occurs is essential as the condition has legitimate and long-lasting effects on people’s well-being. Research focused on trying to understand the experience of burnout shows us that, if not attended to and dealt with soon, people’s physical and mental health may be at permanent risk. The concern, then, is not that we are simply neglecting our health, which we could easily take care of if only we made the time to do so. Rather, our concern should be about whether we even have the time and capacity to attend to the symptoms of our burnout amidst our overworked schedules. As we track the origins of burnout in American society, our concern crystallizes: we have reached an alarming unconscious consensus that our health is no longer an actual priority that necessitates time, especially not when that time could be used for work. As burnout is a matter of health outcomes and not simply work habits, we need to look at solutions to burnout as life-saving treatments, not further optimizing practices.

If the debilitating aspects of burnout come from an overworked, industrialized work-life balance, perhaps an answer to burnout necessitates a total restructuring of the schedule itself. I argue that play is one such way in which we can protect against burnout, which makes it a healthy activity and not a mere frivolity. Playing is not always regarded as a legitimate activity for adults, especially for working adults with careers and/or families to maintain, yet this perspective may directly stem from and feed into the unhealthy pursuit of optimization that makes burnout flourish. If we manage to convince ourselves that work must always come first and therefore convince ourselves that play is, by definition, superfluous, we are also managing to remove from our lives a major way to prevent and relieve stress. Play is not only fun but restorative, with results that directly combat the negative effects of burnout in both the mind and body. Where burnout exhausts the body and depletes its resources, leaving a person sicker and potentially permanently weakened, play reinvigorates; where burnout darkens hope and motivation, leaving a person feeling unmoored and pointless, play holds them and reopens the door to their future. Additionally, when we examine what play affords us both physically and psychologically, there can be no denying that play is inherently healthy alongside delightful. Where burnout depletes and destroys a person’s will, play has the potential to reinvigorate and rebuild a person’s mind and body. Whereas burnout is unhealthy and a byproduct of a dangerous work ethic, play is healthy and a surprisingly accessible and preventative treatment to burnout’s pains.

Conditions Contributing to a Burnt-out Community: A Playless Society

At some point in this country’s history, we began prioritizing work over play and leisure, to the point that our social fabric, our physical health, and mental well-being have suffered. The history of burnout is a surprisingly long one, and it is inextricably tied to U.S. economic history. At the tail-end of the Great Depression, the American Dream offered hope to an impoverished workforce by promising that with just enough work, with just enough time and struggle and grit, any man could make it big. Coming from the mouths of the wealthy, this message seemed to have reliable endorsement It does not matter if you have a higher education (drop out of Harvard, even), and it does not matter if you have an office space or social standing (as long as you have a garage) – if you have a dream and a will, you can have it all. For people so far from having it all, this was an incredible message, and it was a message that made the pain they felt at the end of each day mean something. Buying into the American Dream, devoting any and all of one’s time to working, giving up thought of anything else was easy when the promise of leisure and luxury lay on the horizon. However, people working towards their American Dreams did not foresee another world war that put massive strain on fighting- or working-aged people, nor could they foresee the onset of the Vietnam War a generation later. While World War II severely impacted psyches in its own way, the Vietnam War is directly linked to burnout in that this war-ravaged people both overseas and at home.

In 1973, Dr. Herbert J. Freudenberger coined the term “burnout” to attempt to describe his own experiences of working in multiple therapeutic positions and feeling utterly exhausted after working with traumatized soldiers for over twelve hours a day. Dr. Freudenberger, who sometimes worked 14-15 hours a day and who devoted his time to trying to help traumatized soldiers at the height and end of the war, could only describe the fatigue and futility he was feeling as utterly burning out. Drawing from the experience of chronic drug users, he associated his own symptoms with those of someone addicted to drugs: higher impulsivity, increased risk taking, a looser grasp on the reality currently at hand, etc.[3] Dr. Freudenberger worked with soldiers dependent on medication/heroin to survive the atrocities they faced in the war and who “burned out” on these drugs. The efforts to transition these men back into working society only compounded the effects of the war, generating even greater stress and panic. Beyond Freudenberger’s own experience of burnout, society was facing a widespread risk of its own burnout due to the social climate of the time. Other people who had never even experienced the war, but who had experienced other traumas, reported similar symptoms to the veterans of the war. The more traumatized communities became, the more they burned out, for they were trying to work and engage in a society from a much more precarious position than a non-traumatized peer.

Despite the decades separating us now from the economic and social instability of the 70s, we are still burning out at an alarming high rate. In 2019, Anne Helen Petersen published a book called The Burnout Generation based on her article in Buzzfeed, in which she used this term to characterize her own and other millennials' experience in the workforce. Seen as lazy, spoiled, and childish by older generations, millennial adults struggled to gain their footing in an entirely different economic world than that of their parents. Petersen, although her job did not necessarily suffer much, felt drained, frozen, and unable to do much of anything in other aspects of her life. Petersen realized that she and her peers were too exhausted to do anything because they were working all the time, a message that Petersen saw implicitly and explicitly urged on her since she was young.[4] Now, decades after the war and following multiple economic recessions, many people work so much because not only are they paying for the material goods they may like to possess, the government services they contribute to for the theoretical betterment of every person, but they are also paying the cost of merely living. It is expensive to live, especially when one is not born into any wealth, so this conundrum of why we forsake play for work cannot be put on the shoulders of the individual. While that complicates the question immensely, it does not stop us from asking it. Rather, we must redirect our question towards someone – or something – else. How we pose such a question and when is a matter for an entirely different discussion, so we must return to the main point at hand: we spend so much time working because we must live. When play does not put food on the table, it must take a backseat to the “real” work that can. But this distinction is inherently where our interests lie: What does play provide, since it does not give us the immediate ability to pay the cost of living? Alongside the move towards emphasizing work over everything leisurely, relegating play to a more frivolous position has stripped play of its therapeutic and health-related qualities. In the face of economic utility that seeks to optimize life to the highest financial benefit, even health takes a place on the back burner. For the people struggling to find their footing after the Depression at the expense of their own time and breath, for the veterans of traumatic wars, for the twenty-something-year-olds today who have to choose working an extra shift to make rent over taking a day to rest, health has always come behind profit and productivity. Living in such a way has physical and psychological consequences on a person that need to be proactively addressed.

Research on the Hazard of Burnout in Different Aspects of Adult Life

Conversations about burnout in clinical studies often look at healthcare workers and physicians to ascertain the effects of the condition, because this is a population that consistently works extremely long hours and is almost always understaffed or under-supported. If the conditions leading to burnout include an extremely imbalanced work/play life and a debilitating lack of support, real and perceived, then physicians may be textbook cases for burnout in American society. Now, more than ever, the examination of physician burnout has significant weight as physicians continue to work amidst the global COVID-19 pandemic. The rise of burnout has increased seemingly exponentially since the pandemic began for all workers, even those working from home, but healthcare workers have had to take on a major brunt of the effort in keeping communities afloat. For people working on frontlines during the ongoing pandemic, especially those working in intensive care and specifically COVID-19 units, working has become a legitimately traumatic event. Physicians work day after day in 80-hour weeks to fight off the disastrous effects of the virus in sick patients, but the never-ending influx of critical patients and the steady death rate has started taking its toll on healthcare workers. In September 2020, a study conducted by the American Psychiatric Association concluded that nearly 36% of front-line physicians had symptoms akin to those of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, including but not limited to nightmares, flashbacks, and constant panic attacks.[5] Research on the long-term effects of physician burnout prior to the pandemic have been eye-opening, but these results may hold even more weight now as we continue to move through more unprecedented times.

Previous Research

Burnout has increasingly become the focus of clinical research recently due to the sharp increase of reported cases in working-class adults. Just as Petersen noted in her book and article, more working-class adults entering the workforce have reported experiencing exhaustion, mental health issues, and an alarming decrease in their energy and motivation. With the previous generation starting to retire out of the workforce, burnout sweeping through the remaining and incoming employees is a huge risk to optimal productivity. However, research around burnout has not only focused on studying this experience for the aid of maintaining the workforce but also out of deep concern for people’s long-term well-being. Recently, researchers have observed and tracked multiple health conditions related to burnout, and these conditions may have permanent and severe impacts on people’s lives. The risk of harm necessitates immediate attention and action as these studies reveal a credible risk to people’s physical, psychological, and social health.

Studies have shown that being burnt-out for extended periods of time is associated with cardiovascular diseases, increased pain, a lowered immune system, sleep disorders, and generally poor health habits.[6] A systematic review of 31 studies focused on burnout specifically in physicians found that burnout was a “recognized workplace hazard”[7] that necessitates ongoing proactive measures on both administrative and individual levels. This review compiled a list of symptoms and outcomes of burnout from the 31 studies, most of which reported emotional exhaustion or depersonalization as a major symptom. The outcomes of these studies seem to indicate that “hazard” is describing burnout lightly, as studies reported a range of outcomes from “decline in job satisfaction” and the “intention to leave job” to “body pain” and “daily alcohol consumption”, a “decline of empathy towards patients,” and “medical mistakes” (in which patients were harmed).[8] The words cardiovascular diseases and sleep disorders already carry a fearful weight, but the possibility of decreasing empathy in physicians who people depend on to care for their health and safety is especially frightening. With a reported difference in empathy levels, we can see that burnout not only affects the body but also our psychosocial capacity to be in relation to each other. As many pop-psychology blogs about burnout say, maintaining social connections is extremely important for mediating the effects of burnout – with decreased empathy, though, these relationships may possibly be at risk.

Outside the healthcare field, burnout in the workplace is correlated with workplace conflicts or bullying, which compound other outcomes of burnout in a potentially vicious cycle.[9] Research has also shown that burnout has adverse effects on teachers and students in various disciplines, so much so that the outcomes of burnout in teachers compounds the outcome of burnout in their students.[10] Parental burnout is also prevalent, the outcome of which includes possible addiction and sleep disorders, relational/social conflicts between family members, and an increased risk of neglect and abuse of the child.[11]

Current Implications

There has been a tremendous amount of research on the outcomes of burnout and their potentially devastating effects on our lives, but the startling results and conclusions of these studies still raise the question: What do we need to do to stop people from burning out? Out of all the previously mentioned studies and reviews looking at varying fields and aspects of adult life, burnout has been shown to reduce people’s ability to connect with or even care for each other, as well as diminish people’s capacity for satisfaction in their own lives and potential futures. While the possible physical effects of burnout need to be seriously considered, the potential for burnout to disrupt or damage our ability to see each other as people, to care for each other and help each other, needs to be given more weight in our consideration of burnout’s place in adult life. Most of these studies conclude by calling for precautions to be built into the organization of the workplace: preventative measures that try to ensure people are not working for too long at once, to safeguard against interpersonal conflicts, and to hold administration accountable. All these solutions, however, still act within a theoretical framework in which burnout is localized in the workplace or classroom itself. When the answer to burnout lies in better staffing and scheduling, or better workplace benefits and support networks, or even better accountability measures for when all else fails, we seem to be missing a crucial part of the picture: hat makes people susceptible to burnout prior to working at all?

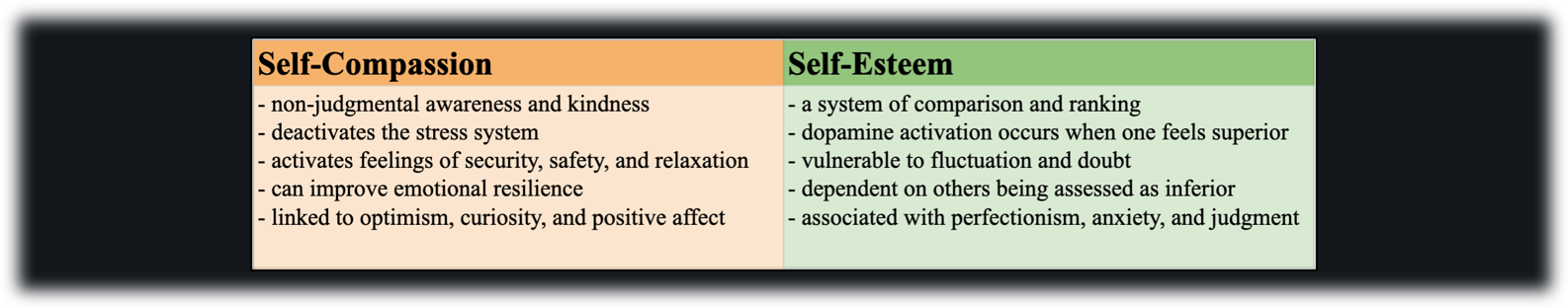

As not every physician, teacher, student, employee, parent, etc. experience symptoms of burnout, we can most likely say that burnout is not a universal inevitability of being an adult, although it may feel otherwise when the effects of burnout affect so many of us. If it’s not universal, what essentially inoculates someone from developing burnout or at least lessens the symptoms of burnout? A Harvard study asked similar questions in 2016, concluding that practices that foster empathy, compassion, and that work towards shifting one’s perspective away from a hypercritical, over-productive mindset help stave off the effects of burnout.[12] Better empathy, compassion, and an improved mindset are ideal but listing these and having these are two different things, which brings us to consider what tangible actions we can take to bring us closer to our goal of preventing burnout. It is with this question that we turn now to discuss play, which is presented here as a tangible and feasible option for preventing burnout.

Playing Again: Play as a Potentially Life-Saving Option

The Surprising Benefits of Play

The health outcomes of chronic and seemingly normalized burnout should push us to look into what we can do to mediate the health risks posed by burnout or, better yet, focus on addressing the deeper conditions contributing to a workforce/lifestyle that continuously burns people out. The previous studies listed various ways of mediating the effects of burnout to help employees feel more able to work or continue in their roles without any more hiccups, but these solutions act more as retroactive remedies for burnout than plans to avoid burnout in the first place. For a solution to our larger burnout problem, and not the problems posed by burnout, we need to explicitly call into question the optimization-based mindset that has, for decades now, deemed it normal and even necessary to have a life built solely around work at the expense of leisure or play (specifically work that contributes, produces, and culminates in some aid for the larger community). Many articles that propose an answer to burnout, some quick and easy fix at little to no cost, that is not inherently accessible, calling people to leave work or simply add one simple task to their day. Taking breaks, building in time for breathing exercises or mindfulness practices, planning after-hour destress events with friends are all actions that a) force us to try and further stretch ourselves to make time for more tasks in our already over-scheduled agendas and b) do nothing to address the fact that we are overscheduled at all. It is not natural, nor should it be considered natural, for people to live their adult lives with chronic pain, stress, and health issues — the very existence of these health risks should tell us that there is nothing natural about working the way we do. What we need to start doing instead, then, is move towards a new framework that disrupts our impulse to optimize our lives to a detrimental point — we need to sort out our priorities and give weight back to play. It is much easier to say this than do this, and it’s worth noting that such a solution requires a massive collective effort, but every large and organized change has to start somewhere, even if that origin seems small.

We can start reprioritizing play in our lives by reconsidering the way we conceive of play’s role in our lives as we age. Play is often thought of as mostly something from children’s lives, such that a child plays while an adult does not. Most definitions or explanations of the word “playful” include some sentiment along the lines that being playful is not being very serious or being in some way childish. Relegating play to just our earlier stages of development cuts us off from the continued and long-lasting benefits play offers for our emotional and physical health. Rather than viewing play as something we grow out of, it may be more beneficial to conceive of play as something that grows with us — play does not have to nor should it look the same to a person when they are two and when they are twenty-two, and that is because the goal of play has to change according to our lives in the playful moment. As a toddler, my goal is to learn how to walk, so I may play by rolling around and toddling from place to place. At twenty-two, I am almost proficient in walking, to say the least, so my play will not look like rolling around on the ground — instead, it may look like reading fantasy novels to better equip my imagination. Just because my play now does not involve full-body activity, nor does it involve toys like blocks or dolls or tea parties, does not make my play any less playful. After all, I am still inherently engaging in a game through which I learn something for and about myself that I will then take with me into future moments.

Play & Health, Physical and Mental

As an adult, play is not only a form of developing skills or learning about my own capabilities as play also has tangible and necessary healing effects that make playing an inherently healthy act. When we play, our minds and bodies take up activities that have beneficial effects on many of our internal systems. Play has been shown to physically reduce the effects of stress in children’s bodies, and considering the physical outcomes of burnout that call our attention and research to the experience in the first place, we should inquire more about play’s possible benefits to physical health. Playing directly affects a child’s neurological development; the same brain regions essential for learning, engaging, and acting as agents in their environments are involved in play: the prefrontal cortex (responsible for most of our executive function such as planning, thinking/working memory, processing, etc.), the amygdala (the center of fear-processing and memory as well as risk assessment), as well as many other regions of the brain.[13] During childhood development, when these brain regions are in their initial stages of growth, play helps the brain develop at a faster rate and with more complexity than brains of children who play less. With such complexity, skills like creativity and critical thinking may come quickly and with more dimension.

For adults whose brains may be nearing or already reached the end of their development, play does not lose its neurobiological importance. With the brain, especially as we age and our neural pathways start to deteriorate, it is a matter of “use it or lose it.” Play acts as a way of practicing and maintaining brain function so that our cognitive functions deteriorate at much slower rates, and we may continue to be creative or imaginative for longer and with barely less dimension. Play is not only a neurological stress reliever, but also a psychological and social relief. In children, play is often a stress-relieving activity in which they are able to have a sense of control or predictability, especially when the rules of the game come from their own minds.[14] For adults, play can also function as a psychological stress reliever by giving us the ability to create a stage on which we write the scripts and control the movement of the players, whether those players be our own person or crochet hooks or soccer balls. Control and predictability both offer a sense of relief, especially when the stressor is an apparent or felt powerlessness and futility that we often see in working.

Play is similar to mindfulness or gratitude exercises that both call for continued practice and ultimately lead to positive habit-forming outcomes. Playing is a self-revitalizing act that makes future playing easier and more accessible. It may seem arduous to try and plan a life fuller of play, especially considering how packed our schedules already seem without this added task. Play, however, resists scheduling and demands spontaneity or else our playful actions become yet another added obligation we have to fill before we have completed our day. How then, does play become part of our lives? At first, we may have to plan in times to play, just as specialists and blog posts call for scheduled breaks into long workdays, but with play, this planning will soon fall away.

One need only look to children for a sense of this. Children, for whom play is routine, the world is not simply the world as we see it; the living room is not just a room, chairs not simply chairs, but instead a fortress, or perhaps a ballroom, or something equally as fantastical. When children play, and especially when they do so with their whole mind and body, every coming moment is a moment of massive potential for playful activity, and the world itself holds more space for play than before. Left in any sort of room, a playful child can make anything out of the space, and it is because they have learned to see the world around them as an inherently playful place. In such a place, possibilities of emotions, actions, and lives are endless, so if children can see the world like this, what is stopping adults? When we play — when we fully let ourselves play and give ourselves up to the possibilities held within play — we fundamentally change. These shifts may be imperceptible yet impactful, for these changes reposition us within our lives to become more capable of play. That stressful day, those piling-up work assignments, the ache in the back that you just cannot shake: these will all still be there after we finish playing, but we ourselves have been able to reposition ourselves to experience these frustrations and pains differently. Play is self-sustaining and self-revitalizing, so while it may be a chore to start playing, it will not take much to keep the ball rolling at fantastical speeds.

Making (and Taking) Time for Play

Scheduling play into our lives sounds easy in practice and yet is rarely so simple. One place in which we may have already created the possible space for play is the therapy session. Play is a valid therapeutic method, and it is especially favored in the therapeutic care of children, so why could it not benefit adults needing therapy as well? Play is a way of practicing using our imagination, a way of letting the boundaries of reality fall away without making ourselves tumble as well. From this creative, unlimited space, we are able to have a level of distance from daily life stressors that allows us to reimagine our lives and imagine a way to get there. While the constraints of our society and environments may have something to say in contention with what we imagine in therapeutic play, the inherent use of imagination and creativity blows open our lives to the option of getting through life’s stressors. What “therapeutic play” looks like may be vague, but not necessarily unattainable — in fact, many therapeutic conversations could be considered a form of play. Oftentimes, playing is easier or more enjoyable when we have someone to play with, either as some kind of companion within the game or a model for the game. Dialogic therapeutic conversations, in which both client and therapist actively take part in and open themselves up to whatever the session’s conversation may be, can be a form of play that embodies this inclination towards playing with as well. Drawing from previous conceptions of play, philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer discusses play in his work, Truth and Method, as an event of suspension and immersion.[15] To Gadamer, play is an active moment which, in order to enter into successfully, requires the player to let themselves become part of the game. In this moment, the hard delineations of the self blur with the play itself. These delineations, although important for the most part, may make people more susceptible to burning out by profoundly isolating them from any inoculative experiences. The merging that occurs in play brings the players to a space in which all of their external ties (the obligations, anxieties, and all that cause the player to build such rigid walls in the first place) are temporarily suspended. This suspension may lead to a much-needed point of catharsis for the players. This play is dynamic and marked by an exchange, either between the player and the play or between players themselves, and this can be found in mutual dialogue. When therapeutic sessions center dialogue between client and therapist, a conversation that asks both people to make themselves open to giving up their firm positions distinct from each other, the healing effects of play may be found.

In creating a clinical environment in which the goal is true dialogue, in which both parties are equally immersed and reciprocating of the other, both client and therapist are able to play around with life stressors while supporting each other in a mutually beneficial event. Therapeutic dialogue can yield more self-understanding and healing because it does not depend on the constraints of diagnostic analyses or protocol-driven techniques. Rather, what makes therapeutic play and dialogue effective is the suspended distance it provides both client and therapist from which both parties may come to a better understanding. As opposed to a more sterile or clinical session, in a playful session, there is the potential for something more to happen other than conversation, and it is this potentiality that may hold a deeper healing quality than the label of mere “talk therapy” can capture. Additionally, incorporating and acknowledging play within therapy helps to bolster the fact that play is a necessary action for someone’s health. Just as medical doctors prescribe medications for illnesses in the body, prescribing or practicing play from a therapeutic perspective emphasizes play as a legitimate treatment for burnout and stress-related illnesses. It may seem arbitrary to prescribe a “dosage” of play because the notion of a daily prescribed amount of play may seem to detract from the spontaneity that makes play playful, but just as mentioned before, this prescription could be the needed push towards self-sustaining treatment. A “prescription” of play for burnout also signifies to us that burnout is something that can be treated, and those who are burnt out are not doomed to a prognosis of feeling apathetic and lost for the remainder of their lives. Although the underlying social and economic organization of our lives work hard to remove any capacity for play from our lives in favor of productive work, we do not have to be fated to be cogs in a machine that will eventually break. Rather, attending to and making time for our needs to play breaks us out of the sharply limited spaces given to us as adults and blows our futures wide open. Instead of living lives defined by work and the fatigue it brings onto our shoulders, we are meant for something more, something fun.

Contributed by: Neha Hazra

Editors: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D. & Jerome Veith, Ph.D.

References

[1] Parton, D. (1980). 9 to 5. On 9 to 5 and odd jobs [MP3 file]. Nashville, Tennessee: RCA Studios. 00:30.

[2] Parton, D. (2021). 5 to 9. On 5 to 9 [MP3 file]. Los Angeles, California: Butterfly Records. 00:58.

[3] Lepore, J. (2021, May 17). Burnout: Modern affliction or human condition? The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/05/24/burnout-modern-affliction-or-human-condition

[4] Petersen, A. H. (2019, January 5). How millennials became the burnout generation. Buzzfeed. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/annehelenpetersen/millennials-burnout-generation-debt-work

[5] Weiner, S. (2021, June 29). For providers with PTSD, the trauma of COVID-19 isn’t over. AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/providers-ptsd-trauma-covid-19-isn-t-over

[6] Salvagioni, D.A.J., Melanda, F.N., Mesas, A.E., González, A.D., Gabani, F.L., & Maffei de Andrade, S. (2017) Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLOS ONE, 12(10): e0185781. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185781

[7] Azam, K., Khan, A., & Alam, M. T. (2017). Causes and adverse impact of physician burnout: A systematic review. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan, 27(7). p. 7.

[8] Azam, 2017, p. 6.

[9] Srivastava, S., & Dey, B. (2020). Workplace bullying and job burnout: A moderated mediation model of emotional intelligence and hardiness. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 28(1), 183-204.

[10] Madigan, D. J., & Kim. L. E. (2021). Does teacher burnout affect students? A systematic review of its association with academic achievement and student-reported outcomes. International Journal of Educational Research, 105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101714

[11] Mikolajczak, M., Brianda, M. E., Avalosse, H., & Roskam, I. (2018). Consequences of parental burnout: Its specific effect on child neglect and violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30, 134-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.025

[12] Wiens, K., & McKee, A. (2016, November 23). Why some people get burned out and others don’t. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-some-people-get-burned-out-and-others-dont

[13] Siviy, S.M. (2016). A brain motivated to play: Insights into the neurobiology of playfulness. Behaviour. 153: 819-844. PMID 29056751 DOI: 10.1163/1568539X-00003349

[14] Gunnar, M. (2020, September 23). Play helps reduce stress. Minnesota Children’s Museum. https://mcm.org/reducing-the-effects-of-stress-on-your-child/

[15] Gadamer, H. (2013). Truth and method. Bloomsbury Academic.