Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Overview

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (HON) first emerged in 1943 when Psychologist Abraham Maslow published “A Theory of Human Motivation” in the journal Motivation and Personality.[1] In this theory, human needs were ordered as a hierarchy in which people could only achieve their highest level of needs after their more basic needs, such as food and water, have been met.[2] Maslow did not claim his theory explained the entirety of human behavior, rather he believed that motivation theory is only a part of behavior theory, because motivation is only a part of human behavior.[3] An intrinsic component of this hypothesis is that human beings will focus on satisfying their lowest level of unfulfilled need first; once that is fulfilled, they can move onto the next level of the hierarchy.[4] Maslow grounded the HON in the belief that motivations of humans should be classified by the goals they are trying to reach instead of by drives or behaviors.[5] This work led him to be categorized as “one of the most influential psychologists of the twentieth century.”[6]

Image source: Simply Psychology[7]

five stages

Maslow’s hierarchy was originally described in five levels, as outlined in the explanation below.

Physiological - Physiological needs are believed to include the most basic biological necessities such as shelter, warmth, sleep, water, and food.[8] Maslow believed “Physiological” needs to be the most basic of all human needs, explaining that if a “man is extremely hungry, he will only think and dream about food.” Illustrating this, is the example that (in the case of chronic hunger) ”a person believes he would be happy if he had an unlimited supply of food”, and would consider that to be Utopia.[9] Maslow believed this level to be the most essential priority by stating that, “Freedom, love, community feeling, respect, philosophy, may all be waved aside as fripperies which are useless since they fail to fill the stomach.”[10] When these basic needs of human survival are not met, an individual may experience illness or the tendency to hoard.[11]

Safety - Safety needs can include having sufficient income, good physical health, and living in a safe environment.[12] Illness and injury are both categorized as safety needs; and Maslow gives the example that when a child is vomiting or in pain, “the appearance of the whole world suddenly changes from sunniness to darkness, so to speak, and becomes a place in which anything at all might happen…”[13]

In Maslow’s original publication, he spent a large portion of this section discussing the needs of children, explaining that predictability and routines are also categorized under “Safety;” anything that is perceived by a child to be unjust or inconsistent will make that child feel unsafe.[14] Children will be terrified by parental outbursts, quarreling, divorce, rages, threats, harsh speech, rough handling, or physical punishment.[15]

In reference to adults, Maslow includes job stability, financial security, and safety from abuse within the umbrella of Safety needs.[16] His publication also suggested that religion, science, and philosophy are the result of the human need to seek safety.[17] When these needs are not met, a person may experience anxiety or psychological trauma.[18]

Love - The need for “Love” includes: love; affection; and belonging in both the aspect of giving and receiving (which can be achieved through social groups, clubs, and online communities).[19] Individuals may achieve the feeling of love and belonging by feeling accepted, making friends, and experiencing emotional intimacy by exchanging affection.[20] In this phase a person may focus solely on the absence of a loved one such as a spouse, child, or lover.[21] In his original work, Maslow made a distinction between love and sex, counting sex, by itself, as a solely Physiological need.[22] When love needs are not met, a person may exhibit antisocial tendencies, or experience loneliness.[23]

Esteem - Self-esteem needs can include a person feeling valued, experiencing competency in their field, experiencing independence to live their lives as they see fit, having respect from others and attaining prestige or fame.[24] Maslow described two subsidiary sets of esteem needs, with the first being the perception others have of us (e.g., attention, admiration, and recognition) and the second including our own sense of importance, appreciation, attention, and prestige.[25] When these needs are not met, a person may experience depression, low self-esteem, or a feeling of worthlessness.[26] Maslow believed that esteem needs could only be met if they were grounded in genuine achievements of the person that generated respect from others.[27]

Self-Actualization - In this stage, people are no longer motivated by gaining something they lack, but by achieving possibilities.[28] Maslow’s theory states that once all of a person’s previous desires and needs were met, they would still not be content unless they engaged in their natural propensity, such as a musician creating music.[29] Self-actualization not only includes creativity but also having strong morals, accepting the imperfections of reality, living responsibly and showing flexibility when pursuing specified goals.[30] The achievement of self-actualization will vary from person to person depending on each individual’s propensity.[31] Since this is the highest level of human need, it focuses on an individual achieving their personal highest levels of fulfillment.[32]

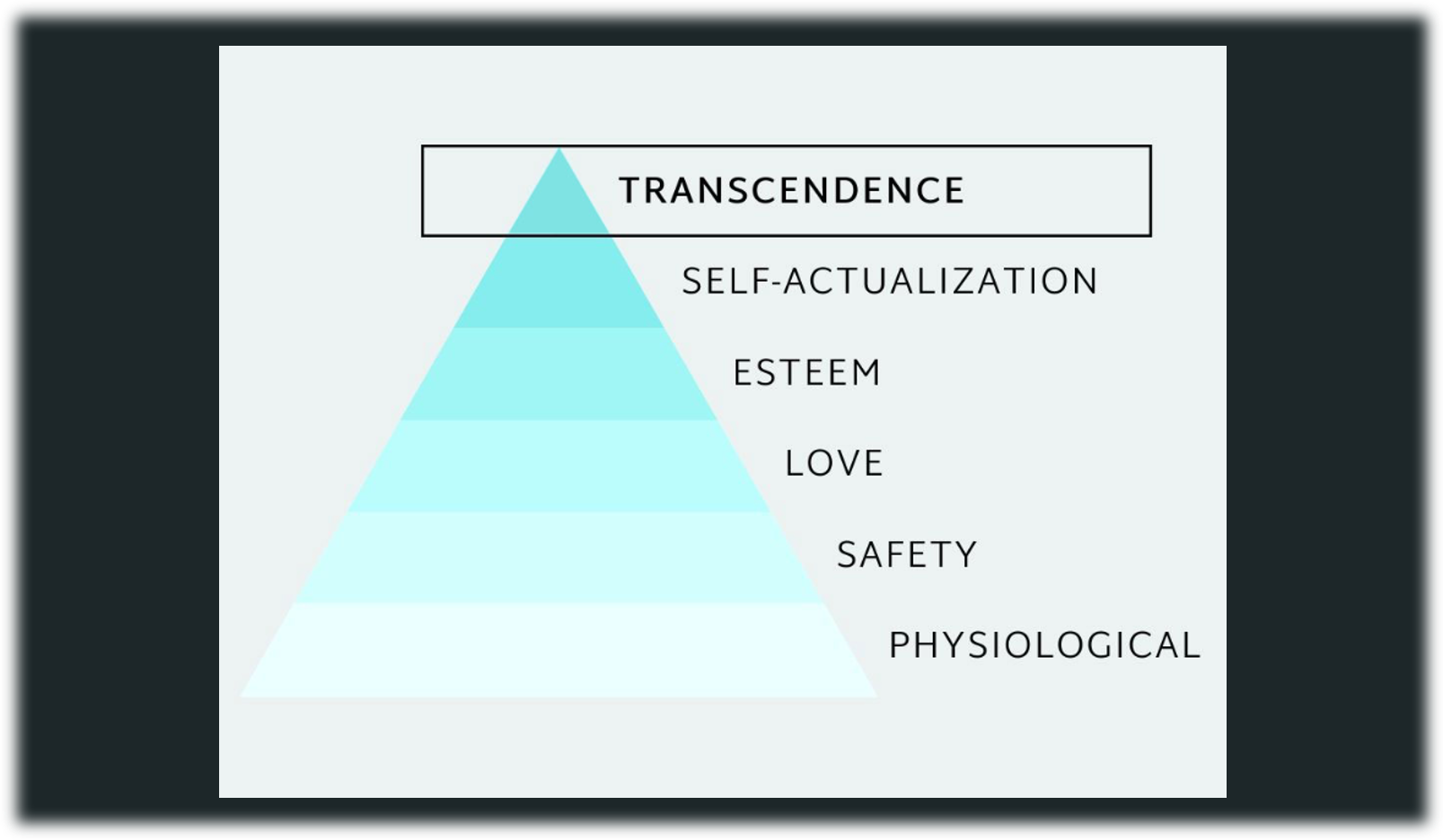

Transcendence - In 1969, Maslow published an article titled, “The Farther Reaches of Human Nature,” in the Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, which proposed that a sixth level of “Transcendence” be added to the hierarchy.[33] Louca et al., (2021) cite Maslow describing this stage as, “It is just this person, in whom ego strength is at its height, who most easily forgets or transcends the ego, becomes unselfish, self-forgetting, egoless…”[34] In this stage, individuals are looking for more meaning to life and begin promoting causes such as social justice or environmentalism.[35] Due to this later addition, the classic pyramid is sometimes presented with a sixth level at the top, such as the one seen in the image below:

Image source: Sloww[36]

History/Development

Abraham Maslow (1908-1970) was an American psychologist who was the child of Russian-Jewish immigrant parents.[37] With distinctively Jewish features, he is reported to have experienced ethnic prejudice and racism, which led him to live a reclusive life and ultimately describe himself as, “neurotic, shy, lonely, and self-reflective” in his teens and twenties, which may have helped to spur his inward level of reflection.[38]

Bridgman et al., (2019) notes that Maslow first conceptualized the idea of his theory when he watched a parade of veterans pass by; not wanting a return to war, he decided to develop a psychology for peace that would speak to “human potential and wholeness.”[39] Concluding that since there was a predominance for lower needs, there must be a hierarchy.[40]

Maslow and the Siksika Blackfoot Nation

Before publishing his work on the HON, Abraham Maslow spent six weeks at the Blackfoot Siksika Reservation in Gleichen, Alberta during the summer of 1938.[41] There has been some discussion as to whether Maslow failed to give credit to the Blackfoot tribe of Southern Alberta in the founding of his theory, and there have been questions raised as to whether this visit impacted not only the development of the HON, but all of Maslow’s later work.[42] Click here to access our interview discussing this controversy.

Maslow was sent to conduct research on the reservation by Ruth Benedict,[43] a pioneering anthropologist at the time who is most well-known for her, “patterns of culture theory”.[44] It is believed Benedict sent Maslow to visit Siksika Blackfoot Nation because she was challenging the idea that competition is an inherently human trait, as opposed to an aspect of Western society, and she thought he would benefit from the cross-cultural experience.[45] However, tribal members reportedly did not appreciate Maslow’s approach to studying their culture, as community members Heavy Head and Narcisse Blood state that he approached studying the tribal members the same way that he approached studying dominance in primates, stripping them of their human qualities and treating them as if they were animals to be observed.[46] Additionally, it has been reported that Maslow did not behave in a way that was welcomed by the tribe, in part because he was asking women in the community questions about topics that were not considered culturally appropriate; they tolerated his presence due to his connection to Benedict.[47]

Though at times, Maslow has been criticized for not giving credit to the Blackfoot Nation for its contributions, research recently published by Kapisi et al., (2022), a team that included Blackfoot researchers, spoke with Elder Melting Tallow who is quoted as saying that Maslow’s hierarchy, “…does not reflect Siksika knowledge, as the nation sees not a hierarchy but rather a circle that surrounds the person, family, community, and which is rooted in cultural beliefs.”[48] Additionally, they add that Maslow’s theory focuses on individual needs rather than those emphasized in collective societies, such as the Blackfoot societal system.[49] While history shows that Maslow was seeking to learn from the Blackfoot community, he has been criticized as viewing it from a “Eurocentric, individualistic lens...” and thus, Kapisi et al. note it is not apparent that any genuine reflection of Siksika knowledge was imbedded in the published version of his theory.[50]

Evolution of the Triangle/Pyramid

Though Maslow’s original article describes the five stages of a hierarchy, evidence suggests that the triangle itself was never created by Maslow, and he did not use this format when presenting his work.[51] However, Maslow did not challenge the presentation of his theory in the form of a triangle/pyramid when it appeared.[52] In 1957, Keith Davis turned the HON into a triangular shape in his publication Human Relations in Business, although it looked quite a bit different from the modern version.

The first time the triangle appears in a version that is close to its modern form was in the article, “How Money Motivates Ment” published in Business Horizons in 1960 by Charles McDermid. Until the 1980s, a ladder was the most common way to demonstrate Maslow’s theory.[53] Despite the popularity of the triangle as a simplified visual display, there are scholars who believe it minimizes Maslow’s intellectual contributions, making them, “bastardized… and reduced to a parody.”[54] Behavior scientists often view Maslow’s pyramid as a quaint visual display with little importance to contemporary psychological theories.[55]

Applications

Since its creation, Maslow’s theory has been widely applied throughout multiple fields including the business, education, medical, and law enforcement sectors. In business, the theory was incorporated by managers as early as 1960, with Texas Instruments using it as a model to redesign jobs from 1966-1970.[56] Since then, managers have applied this theory to enhance the relationship between employees’ sense of fulfilling their ambitions and their performance in the form of rewarding workers with titles, projects, and flexible work environments.[57] The theory drove employers to shift towards not only rewarding employees with financial compensation, but also in developing a relationship where opportunities to fulfill individual ambitions were involved.[58] Maslow continued to utilize his theory while employed at Saga Food Corporation in 1969; there he observed their management training seminars, which he referred to as a “test-tube experiment” for new possibilities of enabling individuals to attain self-actualization through their employment.[59]

For decades, Maslow’s Hierarchy was used within teacher training programs to model how teachers should understand student needs.[60] The education system adopted the hierarchy as an essential component and it is often used to illustrate that students may have trouble achieving their potential if they do not feel safe or have their biological needs met.[61] This has been used to help teachers understand that if students are distracted by having their basic needs met, such as hunger, friendships, or tiredness, they will not be able to focus on learning.[62]

There have also been numerous applications in medical practice. One such example is ensuring that ICU patients are not over-sedated, impairing their overall quality of life.[63] Additionally, during the COVID-19 Pandemic, when nurses were experiencing incredibly high levels of stress and sacrificing their personal needs, research was published modeling how a return to Maslow’s theory helped one organization care for patients while simultaneously meeting nurses needs for safety and trust.[64]

The applications of this theory have been so widely incorporated throughout society that traces can be found in almost every field. For instance, a simplified version of Maslow’s theory, often leaving out the higher level of self-actualization, has been used in police training in England for decades, reducing the hierarchy to a checklist of basic health and safety needs that is referred to in the field as “Doing a Maslow.”[65] On the opposite extreme, one of the more eccentric applications was in 1967, when psychologist Paul Bindrim developed “Nude Psychotherapy,” a method of patients finding their authentic selves through the systematic removal of clothing; he supported his method by citing the work of Abraham Maslow, who was president of the American Psychological Association at the time.[66] These examples provided are just a handful of the seemingly endless ways Maslow’s famous hierarchy has been applied to everyday life and helped to shape modern day practices.

Variations & Criticisms

Image source: Kenrick et al. (2010)[67]

Throughout the application of Maslow’s theory, numerous variations have emerged. There was even a popular meme which featured the classic pyramid with an additional level of “WIFI” featured as the most basic foundational need.[68] The image above is a more serious variation that has been proposed.[69] Illustrating a revision of the pyramid proposed by Kenrick et al., (2010) this includes a history of life-development and reproductive goals in the order they are likely to appear.[70] In this new variation, which uses life-history theory as a basis, self-actualization was removed from the top of the pyramid, under the belief that it is unlikely to be a “distinct human need,” and it is replaced by motivations related to mating and reproduction.[71] However, the creators of this pyramid do note that there may be differences in individual motivations due to between sex variations, within sex variations, ecological factors, and cultural differences.[72] Additionally, individuals who do not feel the need to marry or reproduce, may not be accurately represented in this variation.

The above variation is only one example of the numerous proposed changes and critiques that have targeted Maslow’s theory. While Maslow himself believed that his theory was valid the majority of the time, he acknowledged that there would be notable exceptions. For instance, a person who is continually fighting for lower level needs (such as food), may eventually lose an interest in achieving anything further.[73] Similarly, a martyr might sacrifice their own physical needs for the purpose of a higher ideal.[74]

Maslow’s article additionally included a concept called, “increased frustration-tolerance through early gratification,” which proposes that if a person’s needs are substantially met while they are younger, (e.g., by being well-loved and receiving ample food and medical care) they may later show incredible amounts of tolerance against hatred, opposition, prejudice and persecution enabling them to fight for what they believe despite personal cost.[75] He also acknowledged that on a daily basis most human beings are simultaneously partially satisfied in their various needs at any specific time.[76]

Despite the contradictions Maslow presented in his original article, there have been numerous criticisms of the theory. Since its original publication, variations have continuously been suggested, with some of these attempting to rename how the five levels have been presented.[77] Heslop (2006) notes humanistic psychology in general is often criticized due to its lack of understanding diversity and its emphasis on individualism and the HON is no exception.[78] Critics have also stated that the theory is too simplistic because human beings may focus on meeting more than one level of need at a time and cultures may vary.[79] Additionally, there is evidence to suggest it was founded on the perspective of men and used male values to represent all human beings.[80] Further, critics have argued it is too self-centered and focuses solely on self-actualization while ignoring any contributions of the individual to the larger needs of society.[81] This aspect of the theory may have been influenced by a prominent economic theory, referred to as homo economicus, in which it is assumed that people will always seek their own self-interest.[82]

Perhaps one of the strongest criticisms is that Maslow did not ground his theory in empirical scientific evidence.[83] In fact, he did not support any objective evidence to support his claims.[84] Maslow produced a theory with the expectation that others would go out and prove his work, but Kremer and Hammond (2013) note that those who tried did not produce results that indicated human needs fell into the five categories that were described.[85] The absence of evidence has caused some people to seek removing Maslow’s HON entirely from business textbooks.[86]

Despite criticisms, Maslow’s work has led him to be referred to as the founder of humanistic psychology.[87] In 1961, he founded the Journal of Humanistic Psychology, a subject he developed because he believed behaviorism did not focus enough on how humans differed from animals.[88] Margie Lachman (a Psychologist who currently works in Maslow’s former office at Brandeis University) told the BBC in 2013 that people often miss how he was responsible for a significant shift of focus within psychology by showing that humans are not only motivated by rewards, but also internal needs.[89] Currently, Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs Is still taught as a staple in entry level psychology courses,[90] with the pyramid representation still widely in-use to exhibit the foundation of human needs.

Contributed by: Theresa Nair

Editor: Jennifer (Ghahari) Smith, Ph.D.

REFERENCES

1 Celestine N. Abraham maslow, his theory & contribution to psychology. PositivePsychology.com Web site. https://positivepsychology.com/abraham-maslow/. Updated 2017. Accessed Aug 29, 2022.

2 Gepp K. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs pyramid: Uses and criticism. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs. Updated 2022. Accessed Aug 13, 2022.

3 Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychological review. 1943;50(4):370-396. doi:10.1037/h0054346

4 Celestine (2017)

5 Maslow (1943)

6 Celestine (2017)

7 Mcleod, S. [Maslow's hierarchy of needs]. Simply Psychology Web site. https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html. Updated 2022. Accessed Aug 13, 2022.

8 Gepp (2022)

9 Maslow (1943)

10 Ibid.

11 Gepp (2022)

12 Ibid.

13 Maslow (1943)

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Celestine (2017)

17 Maslow (1943)

18 Gepp (2022)

19 Celestine (2017)

20 Gepp (2022)

21 Maslow (1943)

22 Ibid.

23 Gepp (2022)

24 Ibid.

25 Celestine (2017)

26 Gepp (2022)

27 Maslow (1943)

28 Gepp (2022)

29 Celestine (2017)

30 Gepp (2022)

31 Maslow (1943)

32 Etzioni A. The Moral Wrestler: Ignored by Maslow. Society (New Brunswick). 2017;54(6):512-519. doi:10.1007/s12115-017-0200-3

33 Koltko-Rivera ME. Rediscovering the Later Version of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Self-Transcendence and Opportunities for Theory, Research, and Unification. Review of general psychology. 2006;10(4):302-317. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.10.4.302

34 Louca E, Esmailnia S, Thoma N. A Critical Review of Maslow’s Theory of Spirituality. Journal of spirituality in mental health. 2021;ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print):1-17. doi:10.1080/19349637.2021.1932694

35 Celestine (2017)

36 Kowalski K. What is transcendence? the top of maslow's hierarchy of needs (+ visual). Sloww Web site. https://www.sloww.co/transcendence-maslow/. Updated 2019. Accessed Aug 29, 2022.

37 Cherry K. Abraham maslow is the founder of humanistic psychology. Verywell Mind Web site. https://www.verywellmind.com/biography-of-abraham-maslow-1908-1970-2795524. Updated 2020. Accessed Sep 2, 2022.

38 Celestine (2017)

39 Bridgman T, Cummings S, Ballard J. Who Built Maslow’s Pyramid? A History of the Creation of Management Studies’ Most Famous Symbol and Its Implications for Management Education. Academy of Management learning & education. 2019;18(1):81-98. doi:10.5465/amle.2017.0351

40 Ibid.

41 Feigenbaum KD, Smith RA. Historical Narratives: Abraham Maslow and Blackfoot Interpretations. The Humanistic psychologist. 2020;48(3):232-243. doi:10.1037/hum0000145

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 Benedict, ruth fulton. National Women’s Hall of Fame Web site. https://www.womenofthehall.org/inductee/ruth-fulton-benedict/. Accessed Aug 29, 2022.

45 Kapisi O, Choate PW, Lindstrom G. Reconsidering Maslow and the hierarchy of needs from a First Nations’ perspective. Aotearoa New Zealand social work. 2022;34(2):30-.

46 Feigenbaum & Smith (2020)

47 Kapisi et al. (2022)

48 Ibid.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid.

51 Bridgman et al. (2019)

52 Kapisi et al. (2022)

53 Bridgman et al. (2019)

54 Ibid.

55 Kenrick DT, Griskevicius V, Neuberg SL, Schaller M. Renovating the Pyramid of Needs: Contemporary Extensions Built Upon Ancient Foundations. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5(3):292-314. doi:10.1177/1745691610369469

56 Lussier K. Of Maslow, motives, and managers: The hierarchy of needs in American business, 1960–1985. Journal of the history of the behavioral sciences. 2019;55(4):319-341. doi:10.1002/jhbs.21992

57 Kremer W, Hammond C. Abraham maslow and the pyramid that beguiled business. BBC News. -08-31 2013. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-23902918. Accessed Aug 29, 2022.

58 Ibid.

59 Lussier (2019)

60 Panka L. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in schools. . 2022. https://csaedu.com/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs-in-schools/. Accessed Aug 13, 2022.

61 Gepp (2022)

62 Kurt DS. Maslow's hierarchy of needs in education. 2020. https://educationlibrary.org/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs-in-education/. Accessed Aug 29, 2022.

63 Gepp (2022)

64 Hayre-Kwan S, Quinn B, Chu T, Orr P, Snoke J. Nursing and Maslow’s Hierarchy; A Health Care Pyramid Approach to Safety and Security During a Global Pandemic. Nurse leader. 2021;19(6):590-595. doi:10.1016/j.mnl.2021.08.013

65 Heslop R. “Doing a Maslow”: Humanistic Education and Diversity in Police Training. Police journal (Chichester). 2006;79(4):331-341. doi:10.1350/pojo.2006.79.4.331

66 Nicholson I. Baring the soul: Paul Bindrim, Abraham Maslow and “Nude psychotherapy.” Journal of the history of the behavioral sciences. 2007;43(4):337-359. doi:10.1002/jhbs.20272

67 Kenrick et al. (2010)

68 Kremer & Hammond (2013)

69 Kenrick et al. (2010)

70 Ibid.

71 Ibid.

72 Ibid.

73 Maslow (1943)

74 Ibid.

75 Ibid.

76 Ibid.

77 Bridgman et al. (2019)

78 Heslop (2006)

79 Bridgman et al. (2019)

80 Heslop (2006)

81 Etzioni (2017)

82 Ibid.

83 Kremer & Hammond (2013)

84 Bridgman et al. (2019)

85 Kremer & Hammond (2013)

86 Ibid.

87 Heslop (2006)

88 Celestine (2017)

89 Kremer & Hammond (2013)

90 Celestine (2017)